What does the recent mass firing of National Basketball Association coaches have to do with the rapid turnover of school chiefs? Each illustrates our craving for instant gratification—and each comes at a high cost.

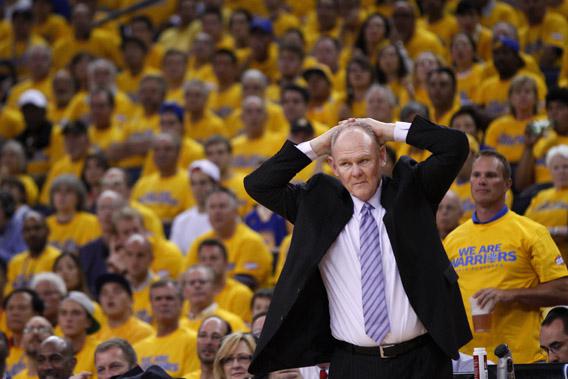

A dozen NBA coaches (out of 30) have gotten the boot in recent weeks—and not only those whose teams compiled losing records. Five coaches whose teams made the playoffs received pink slips. That’s “stupid,” says the Denver Nuggets’ George Karl, who, despite being named the coach of the year, was also fired. Who can disagree? It makes no sense to fire a coach with a record of solid accomplishment.

The same unhappy pattern holds true for public school systems, where the average tenure of an urban superintendent is less than three years. The storyline is all too familiar. A new school chief is hired amid much fanfare and sky-high expectations. Steady improvement won’t do. Unless there’s a dramatic change in fortunes, the grumbling starts, and soon afterward the superintendent is looking for a new job. That’s a sure prescription for failure, since there’s no way that a school chief, however talented or inspiring, can make a lasting difference in such a short time.

In researching my book Improbable Scholars: The Rebirth of a Great American School System and a Blueprint for America’s Schools, I found that successful school districts were far more willing to give their superintendents a real chance to prove themselves.

In these districts, the political leadership didn’t expect Superman to show up. They didn’t press the panic button when test scores didn’t go through the roof, nor did they make perform-or-else demands. School officials didn’t feel the unceasing pressure that, in many communities, has led to widespread cheating to inflate students’ test scores.

The most effective superintendents have remained on the job for a decade or more. The resulting stability has given them the chance to build a school culture that joins high expectations with a sense of trust and shared mission. That’s a foundation on which their successors can build.

Improbable Scholars is replete with success stories—here, in capsule form, are two of them.

The schools in Union City, N.J., a poor Latino immigrant community, used to be the state’s laughing stock. No more. After years of instability and a threatened state takeover, the district adopted a slow-and-steady approach. Union City has had just two superintendents in a quarter century. Now it boasts world-class preschools, a rigorous district-wide curriculum (critical in poor communities, where families frequently move during the school year), assessments that are used to pinpoint help for struggling students, mentoring and coaching for teachers, who work closely with one another, and a nationally recognized bilingual program that enables teen immigrants, who arrive in the U.S. with a bare-bones education, to graduate in four years. Students’ scores on the state’s high-stakes test have come to approximate the statewide average, and the graduation rate is 90 percent, which is 15 percent higher than the national average.

Montgomery County, Md., the 17th largest school system in the nation, used to operate what amounted to two districts, separate and unequal. While students from well-to-do families excelled, a few miles away, kids living in mostly poor and minority neighborhoods dropped out in droves. The school board had booted out several superintendents. Then in 1998 the board picked Jerry Weast to lead the district—and gave him a decent chance. During his 12-year tenure, Weast turned the situation around. He poured resources into the less wealthy schools, and students’ performance steadily improved. Meanwhile, academic standards rose district-wide, with a new push to expand enrollment in eighth-grade algebra (a marker for college enrollment) and advanced placement classes. Students in the well-off neighborhood schools did better. Meanwhile, new community liaisons reached out to parents. The teachers union, invited to discuss policy and not just salaries, went from adversary to partner. Across the district graduation rates rose, and the achievement gap between the schools with poor and affluent populations keeps shrinking.

Longevity on the job doesn’t guarantee results, of course, and some superintendents deserve to be sacked. But I don’t know of a single instance in which a new school chief has transformed a district in the short grace period they’re typically allotted. Schools are simply too complex, and the task of embedding a we-can-do-it culture too daunting, to be accomplished overnight.

Much the same holds true for coaches in the NBA. The two teams in this year’s finals, the San Antonio Spurs and the Miami Heat, remain avatars of stability. In Miami, Pat Riley has been at the helm, as coach or general manager, for 18 years. San Antonio has had the same coach, Greg Popovich, for 17 years. “The continuity breeds trust, it breeds camaraderie, it breeds a feeling of responsibility that each member holds towards the other,” Popovich told an AP reporter, “the ability to be excited for each other’s success, not to develop territory and walls, but to stay participatory. To be able to discuss, to argue and come out at the end on the same page with the same passion and the same goals.”

“And I think without continuity that’s pretty impossible,” the coach added, “because all the immediate tendencies of instant success starts to take over and that just breeds failure.” He could have been talking about America’s schools.