Each week, Roads & Kingdoms and Slate publish a new dispatch from around the globe. For more foreign correspondence mixed with food, war, travel, and photography, visit their online magazine or follow @roadskingdoms on Twitter.

The state of Kelantan moves to a different rhythm from the rest of Malaysia. It’s the Islamic heartland of the country, where the weekend starts on Thursday evening to free up Friday for prayer congregations. Walking past the Siti Khadijah Central Market—where female traders have traditionally been dominant—I see a poster warning Muslim women to refrain from wearing “sexy” or “tight” clothing, or risk a fine up to 1,000 ringgit and/or imprisonment for up to six months. “Guard your honor,” it decrees.

I enter an old building and climb a flight of stairs to a community club hall, where a small crowd had gathered, mostly local university students, girls and boys sitting in separate sections. Their chatter drops to a hush as the show begins: “Once upon a time, in a galaxy far, far away …”

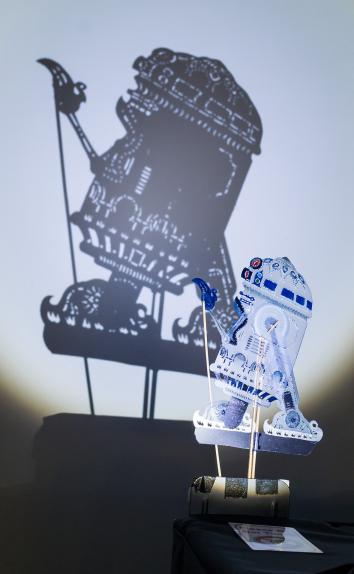

The words, however, appear in Malay, projected onto a white, muslin cloth mounted on a metal frame on a stage. A man sits cross-legged behind the cloth and begins to narrate, waiting to trot out puppet versions of the usual suspects from the first 20 minutes of the 1977 Star Wars film, Episode IV: A New Hope.

The Malaysian art of puppet theater is called wayang kulit—literally, “theater of skin,” for the cowhide used to make the puppets—and this man is the all-important tok dalang, or master puppeteer. Muhammad Dain Othman, 64, whom everyone calls Pak (“Uncle”) Dain, most enjoys playing the villain. Darth Vader makes a grand entrance, accompanied by the digital distortion of Pak Dain’s voice and the familiar refrain of “The Imperial March,” played by a live, nine-man band wielding traditional percussion instruments, with the plaintive wail of the double-reed oboe, the serunai, leading the melody.

Wayang kulit has not always had such a positive reception in Kelantan. In 1990, the Islamist Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party, or PAS, was elected to the state government and outlawed wayang kulit, along with other traditional Malay performance arts. PAS instituted the ban to root out what it sees as un-Islamic influences, because many of these art forms, including wayang kulit, are rooted in Hindu and animist traditions, which held sway over Southeast Asia before Islam arrived. The ban seemed nonsensical to most residents, considering the tradition goes back more than 250 years in this region and is primarily practiced by Malays, who make up 95 percent of the state population and who are predominantly Muslim (Malays are considered to be Muslims under the Malaysian Constitution). In reality, culture and religion are not so neatly aligned, and the ban is emblematic of the conflict between Malaysia’s pluralist history and the Islamist political vision that is on the rise, influenced by movements in the Middle East.

Despite the ban, performances continued because of wayang kulit’s long-established role in the lives of the Kelantanese, though the number of master puppeteers has dwindled to fewer than 10. Pak Dain says that the ban has since been relaxed and that performances are permitted if they eschew the traditional Hindu Ramayana epic for stories from Malay literature, emphasize morality, and are intended for entertainment purposes only. Still, Pak Dain says that most master puppeteers tend to stick to the Ramayana epic as it’s synonymous with wayang kulit and that they have nonetheless avoided repercussions. Institutionally approved performances catering primarily to tourists take place at the Cultural Center of Kota Bharu while the authorities turn a blind eye to shows performed in the villages.

The Star Wars–inspired wayang kulit performance has the approval of the tourism ministry. It’s the brainchild of two friends from Kuala Lumpur, “Tintoy” Chuo and Teh Take Huat, a character designer for video games and an art director at an advertising agency. Aside from indulging their geek fandom, they hope to bring more young people to wayang kulit. Using Star Wars to popularize, well, anything is a familiar trope, and for good reason: It’s effective. As Tintoy says, “Even my mother knows who Darth Vader is.” It’s why this evening’s performance was happening, at the request of a British television crew filming a travel show. And it’s partly why I, hitherto ignorant of my own country’s traditional arts, had come to Kelantan.

Teh Take Huat

Pak Dain waited several months before finally agreeing to a collaboration for a show. “Pak Dain is a traditional Kelantanese puppeteer, and he wanted to make sure that we were committed to doing it correctly,” Tintoy says.

Ultimately, Pak Dain was satisfied that the Star Wars story and the modifications required to tell it—the projector used instead of a bulb for backlighting, the plastic used to make the white Stormtroopers because cowhide was too yellow, the motifs and details added to the Star Wars puppets to localize them—were compatible with wayang kulit, because it’s a form that inherently provides ample room for improvisation. The more challenging task was getting Pak Dain to watch A New Hope, Take Huat jokes. “We would call him and he would say, ‘I’ll watch it next week.’ Then we would call him again, and he would say, ‘OK, next week.’ ”

Eddin Khoo, the founder of an organization called Pusaka, which documents and conserves Malaysia’s traditional performance arts, is decidedly skeptical about the Star Wars project, calling it “gimmicky.” He’s bothered by the idea that it might be “reviving” or “modernizing” the art form. “In fact, wayang kulit has never not evolved. It has constantly adapted with the times, and that’s nothing new,” he says.

Khoo explains that wayang kulit in Kelantan has been heavily adapted to the local context. The main narrative—which would take at least 30 days to perform in its entirety—is derived from the ancient Ramayana epic about an exiled prince (whose name is changed to “Seri Rama” in the Malay context) on a quest to rescue his beautiful wife, Sita Dewi, from the evil Ravana, known here as Maharaja Wana. Most notably, it underwent a process of secularization. “Wayang kulit is mainly practiced here by Malay-Muslims, and they cannot deify this tradition. So they’ve made the Ramayana epic more human, more like themselves,” he says. The result is the Hikayat Maharaja Wana, where the focus shifts from Seri Rama, the hero prince, to Maharaja Wana, the central antagonist.

“Seri Rama is actually despised by many people in Kelantan because he is vain, arrogant, and egotistical,” Khoo says. “On the other hand, Maharaja Wana has great sympathy among the people. He may be a kidnapper and a thug, but his love for Siti Dewi is more sincere and more pure than Seri Rama’s love for her.” Unlike in India, where Ramayana is regarded as a deity, the Malay retelling doesn’t glorify the prince.

Then, there was the rise of “modern” wayang kulit, which Pak Dain and Khoo both credit to the late master puppeteer Dollah Abdullah Ibrahim, known as Dollah Baju Merah. He earned a reputation in Kelantan for his bold innovations before he passed away in 2005. He continued to work within the framework of the Hikayat Maharaja Wana but brought in foreign elements, like Bollywood music, as well as integrating political satire and humorous social commentary. Khoo worked with him closely for many years and describes him affectionately as a dalang samseng: hooligan puppeteer. One of his most memorable performances featured an imam puppet with a permanent erection. Pak Dain recalls another performance, attended by the local police, in which Dollah Baju Merah mercilessly mocked corrupt policemen. He was shut down midshow and banned from performing for a year. As Khoo says, wayang kulit isn’t just about telling a story: “It can be very subversive, a danger to formal politics.”

It’s not clear who will take on Ibrahim’s mantel. His troupe took three years to recover from his passing before bringing on a new master puppeteer. Today, it’s led by 60-year-old Muhammad Noor Hasson, known as Pak Nawi, and the master musician Abdul Rahman. I went to visit them in a Malay village that’s a 40-minute drive from Kota Bharu to experience a traditional wayang kulit performance.

The troupe had decided to perform last minute, but there was no hurried powwow before they opened the show, no talk of what story would be performed, no ironing out of logistics. Instead, we lounged on the veranda of Rahman’s house while discussing the virtues and foibles of the characters in the Ramayanic universe. The troupe members knew their repertoire so well they were ready to perform at a moment’s notice. The genius of a master puppeteer is his ability to improvise, to pick a story based on the audience and the mood of the troupe. No two performances—even of the same story—are ever the same.

Once it was dark out, we moved to an open pavilion in the village reserved for community events. Pak Nawi took his seat on the floor and puffed on what remained of his cigarette, his hat spun impishly backward and puppets at the ready, while the band sitting behind him launched into the opening score. Men, women, and children had gathered before the pavilion as well as behind it, to better watch Pak Nawi weave his subtle magic as he called upon the full range of his voice, mannerisms, and wit to bring each character to life.

I didn’t detect anything subversive in the performance, but perhaps the fact that it was happening at all was enough. Unlike Dollah Baju Merah, Pak Nawi adheres to the traditional school of wayang kulit, which he says emphasizes the story over easy laughs, although there was plenty of laughter. He spoke in dialogue and poetry, he sang, and when it was called for, he screeched. It was all very informal: The troupe talked and laughed between acts. The audience came and went, and then came back. Unlike at the community club hall in the city, where the stage was elevated and at a distance, there was an intimacy and immediacy to the performance here that was exhilarating.

Beyond the broad outline of what was happening—a confrontation between Seri Rama and two warriors serving Maharaja Wana—I didn’t understand very much of what was going on. The play was performed in the customary Kelantanese-Pattani dialect of Malay, which is distinct from the formal Malay language I learned at school. But I remembered something Khoo had said.

“Look, wayang kulit is not about understanding, sometimes,” he told me. “It’s a total experience. Liberate your senses from the mind, man.”