Ruth,

You asked who I think gambles with Israel’s future, the left or the right, the hawks or the doves. My answer comes from your uncle, Meir Amir, who emailed me from Tel Aviv:

What Netanyahu is doing is gambling with the future of Israel, at least with its future as a Jewish democratic state. That’s what liberals think and it is their duty to convey their opinion on that matter.

Here’s another way to put it, from Jeffrey Goldberg, who talked about Gaza a couple of weeks ago as a guest on the Slate Political Gabfest. We were discussing the shifting demographics, which suggest that if Israel does not leave the West Bank and Gaza in the not so distant future, there will be more Palestinians than Jews in the land under Israel’s control, threatening its fundamental democratic principles and character. This is part of the reason the status quo is not sustainable, Jeff said. “My argument is that if you allow the West Bank and possibly Gaza to become independent, you might have a terrible security problem on your hands in future years. If you don’t, you’re definitely going to have a problem in future years.”

This is where I come out too. And, regardless of timing, I can’t imagine a reason not to say it, or write it.

Now for my tack in the other direction: I also identify with Jeff’s recent column about the Gaza operation, which is largely defensive of Israel. “What would you want your government to do if your enemy was digging tunnels under your village, in order to pop out at night to kill or kidnap you?” he wrote. “An honest person would answer this question the following way: I would prefer that my government do whatever it must do to make sure that terrorists are not constructing tunnels under my house in order to kidnap me or members of my family.”

If that’s the framing, then, yes. As my Israeli friend Jeremy Leigh emails, citing the writer Yossi Klein Halevi:

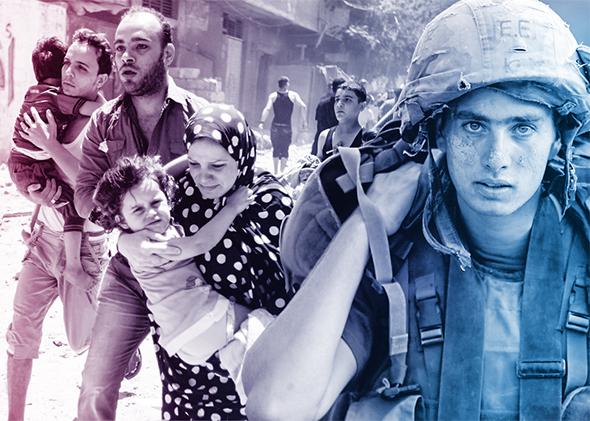

Left wing Jews should not allow themselves to be guilty of the crime of ingratitude with regards to the idea of Jewish power. It was not fun being Jewish without having power in the world—statehood is about many things and one of them is about having power: military, diplomatic, etc. It might be tempting to live in a morally easier place when power is just intellectual, a bit economic, but it cannot offer the guarantees that statehood affords. So, ugly though it is to see people being killed by our soldiers, that is just the way it works in the grown up world. On the broad level there are rules of war to keep things in check. But as it pertains to the particular moral space inhabited by the left, it means having to accept that war happens, people get killed, even children. Awful but sobering and true.

Yes. But yes also to the concerns about excessive force, Israeli government intransigence, and Netanyahu’s failures of leadership that Klein, Chait, and Cohen raised. This is the moment to make those points, wherever you live, if that’s where your mind and your heart take you. Making them, as a diaspora Jew, is not a veiled threat to withdraw your support for the country and its people if the government doesn’t change. Nor does it distance you from Israel. It is a form of engagement.

Jeremy, who leads Jewish Journeys to countries all over the world, including Israel, is wise about this: “Israel is a functioning democracy with a huge breadth of internal debate—diaspora Jews are going to become part of that. It does not make sense that diaspora Jews are going to stand on the sidelines, expressing the ‘solidarity’ impulse without activating the intelligent engagement reflex too. If settlement policy makes no sense, then surely they would say it.”

When Israel is at the forefront of the news, Jewish liberals can keep their mouths shut. They can read back Netanyahu’s talking points. Or they can seize the opportunity to focus on pressuring the government to move toward a two-state solution, and away from moral and demographic calamity. Or they can try to do a dance of “yes, but, and,” which is where I always end up. This is why I almost never write about Israel. I’m tempted to attach so many qualifications that I am constantly contradicting myself. In a room of Jews who I think are knee-jerk defenders of the government, I’m a critic. When I’m talking to Jewish or non-Jewish friends appalled by the death toll and the images from Gaza, I remind them what Israel is up against and why its existence is absolutely necessary. About that Zionist core, I’m as clear as Chait is: It’s immutable.

You asked what I make of Shmuel Rosner’s idea that if Jews are a family, then it’s “natural for Israelis to expect the unconditional love of their non-Israeli Jewish kin.” I like his family metaphor, but I think that in a family, unconditional love and criticism go hand in hand. Meir writes: “You love your son but you don’t stop criticizing him if that is what is needed.” American Jews aren’t really the parents in this relationship. We’re the cousins, or maybe, the brothers and sisters. But the basic truth holds. “Israel needs to be able to defend itself in factual terms, because most people in the world are not Jewish,” Chait writes. Sometimes your family holds up the mirror that helps you present yourself to the world.

Here’s another point I can make without ducking and weaving: What diaspora Jews say and feel about Israel matters more to us than it does to Israelis. We have limited influence over our own governments’ policies toward Israel. We don’t vote for Knesset or prime minister. When the center-left author Ari Shavit writes an amazing, provocative book about Israeli history that struggles with the expulsion of Arabs in the crucible of the country’s founding, maybe he will make some of his Israeli readers think anew. When I write, I really doubt it. “Perhaps this is a weakness, but Jews tend to listen to those who argue from inside rather than outside,” Jonathan Freedland wrote in reviewing Shavit’s My Promised Land in the New York Review of Books. “Witness the Haggadah’s distinction at the seder table between the wise son and the wicked. Technically, all that separates them is the grammatical difference between the first and second person. What does this mean to you, asks the wicked son; what does this mean to us, asks the wise son. But that distinction makes all the difference.”

Oh no, did I just turn diaspora Jews into a bunch of wicked sons? That’s not my intention—block that metaphor! My point is this: When we wrestle with any aspect of the conflict, from Gaza to the settlements to Hamas, we are wrestling with our own sense of “the meaning of being connected to Israel,” as Jeremy put it to me.

Maybe like some of you who are reading along, I think a lot about what I’m teaching my children. My husband and I took ours to Israel three years ago. They loved it. We got to have seder with your aunt and uncle and cousins, and my kids couldn’t get over how it zipped along with native Hebrew speakers. And/but: Here is one story about that trip. On a hike in Ein Gedi, a beautiful nature preserve on the eastern border of the Judean Desert, a pair of guards came running after us. They told us to turn back. I asked why. They wouldn’t say. We looked ahead, and in the distance, up the hillside, we saw what looked (from their clothing and headscarves) like a Palestinian family having a picnic. Ein Gedi, it turns out, is just inside the 1948 armistice line, which means it borders the West Bank.

I don’t know who the people we saw were. But there were children in their group, too. As the guards hustled up the hill to turn them around, I told my kids that it was one tiny sorrow in a much larger tragedy that we couldn’t walk by those other kids, out for a hike like we were, and wave hello.

We will go back to Israel. And we will keep talking about everything we see. Ruth, what will you teach your kids? Will it be different if they’re born in New York, where you are now, or in Tel Aviv?