It’s hard to say what the Founding Fathers would think of the modern presidency. But there’s no doubt they’d be horrified by the modern presidential campaign. In their day, no man worthy of the presidency would ever stoop to campaigning for it. George Washington was asked to serve. Decades later his successors were also expected to sit by the phone. “The Presidency is not an office to be either solicited or declined,” wrote Rep. William Lowndes of South Carolina in 1821. Rutherford B. Hayes wanted to be so free of the taint of self-interest he didn’t even vote for himself in the election of 1876. As late as 1916, President Woodrow Wilson called campaigning “a great interruption to the rational consideration of public questions.”

Not so today. Mitt Romney has been running for president for six years. Barack Obama has arguably never stopped since he took the oath of office. Today campaigning isn’t an “interruption” but a permanent condition. Indeed, if you are a successful campaigner it’s expected you’ll be a successful president. In 1992, after Bill Clinton beat George Bush, Dan Quayle said, “If he governs as well as he campaigned, the country will be all right.” Republicans had argued Clinton’s character faults disqualified him from office. Quayle was articulating the common modern view—ratified by voters—that being a gifted campaigner was the more important quality. When Barack Obama was asked about his lack of executive experience in 2008, he pointed to his successful campaign as proof he could manage the presidency. Bill Clinton testified on his behalf: “If you have any doubt about Senator Obama’s ability to be the chief executive,” Clinton said at one of Obama’s vast rallies in October 2008, “just look at all of you. … He has executed this campaign.”

There are similarities between the campaign and the presidency. Both tasks require a candidate to perform well under pressure, communicate effectively, and build a team that trusts you and can function with little sleep and lots of stress. Obama political adviser David Axelrod says the crucible of the campaign uncovers the hidden personal qualities that you can’t list on a résumé. “It’s an MRI for the soul,” he says.

But if good campaigners made good presidents, we’d have a constant string of successes. Most sitting presidents, almost by definition, have been skilled on the campaign trail. Yet the talents do not necessarily convey. Lyndon Johnson crushed Barry Goldwater in 1964 in part because of his attention to the minutia of the contest. He carried a laminated card in his pocket of the key polls in each battleground state, but Vietnam was beyond his ability to micromanage. Nixon and his men brought modern public relations techniques to the presidency in 1968. As president, he trampled on the office. In 1974, Jimmy Carter was such a political unknown that no one on the game show What’s My Line recognized him. Two years later he was president. Wise men considered Carter’s meteoric rise proof that he was a political genius. Maybe he was. But he was also one of our least effective presidents.

Campaigns reward fighters. Governing requires cooperation, compromise, and negotiation. Campaigns focus on one opponent, but a president, even if he wants to go on the attack, never has just one jaw to swing at. President Obama must attack the Republican Congress—John Boehner one day, Paul Ryan the next. It was easier to slug John McCain again and again.

Presidential campaigns are fantastical places. Here, on the campaign stump, the United States can be ruthless with China diplomatically—but not beholden to Beijing as creditors. Entitlements are always safe—even as the deficit is drastically cut. Candidates build an electoral coalition by papering over differences and offending no one. Then, as president, they are forced to make choices which almost always offend some wing of the coalition they built.

When voters evaluate a candidate’s character, they tend to be Manichean: Candidates are only one thing or its opposite. A candidate is either a leader or a ponderous professor, a man of the people or an elitist, the real deal or a phony. One-dimensional characterizations makes for easy political attacks and self-satisfaction among those who simply want to affirm their existing ideologies. It is the laziness underpinning much talk radio, but it misses the essential paradox of the presidency: presidents move between both ends of a spectrum.

The cheap political critique of Mitt Romney is that he flip-flops. His opponents point this out as if that’s all you need to know to disqualify him. But malleability is a necessary quality in a president. (Constancy has a nice romantic ring to it, but does anyone want a leader who sets a course and then refuses to change it no matter what?) It’s more fruitful to examine the specific cases where Romney showed flexibility, compare them with cases when President Obama changed his position, and then decide which candidate acted out of a lack of conviction and which was simply light on his feet.

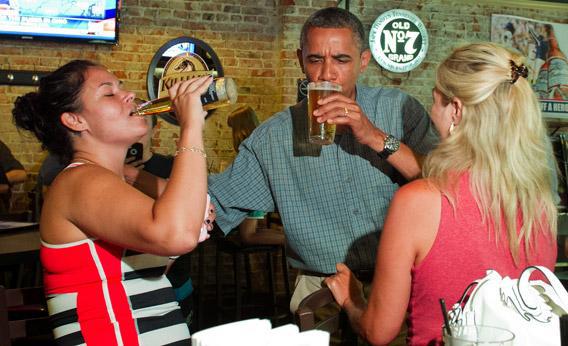

Photo by Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images.

You can test presidential candidates by measuring them against the current occupant. Or you can hold them up against an idealized version and see how they do. It’s probably fairest to match their promises with their skills. Mitt Romney promises to repeal the Affordable Care Act and replace it with an alternative. For those who hate Obamacare, that’s all they need to hear. But simply asking “How?” puts us in a better position to evaluate his theoretical presidency. He’ll need a majority in Congress if he wants to follow through on this promise. The Democrats might still control the Senate. That means Romney will need considerable skill working with the other party to get what he wants. What experience in his background gives us confidence that he’ll have the tools for the job he assigns himself? He’ll also be facing the “fiscal cliff”—an immediate bewildering thicket of tax cuts and spending reductions. How will he manage that and take on repealing health care? Isn’t one of these more important than the other? That raises questions about his priorities and how he sets them. Is he a pragmatist? Or is he an ideologue? Does he have the perseverance to handle both jobs? Would any president?

Maybe there is a better way to evaluate our presidential candidates, and come to more reliable conclusions about which ones are likely to have the skills actually required for the job.

Al Gore once suggested that running for president was like a job interview. But suppose the current presidential campaign were an extended job interview, conducted by the American people. Candidates are so guarded, the hiring committee would have little to go on. He speaks a great deal but says so little. All I really know is that he loves this company and thinks its best days are ahead of it. He thinks the head office in D.C. is out of touch with customers. Great teeth. No applicant would ever get a job giving the vague answers our candidates do.

The usual proposed remedy for the sorry state of our presidential campaigns is more focus on the issues. That’s important in order to learn what a candidate believes, to see if he can set priorities, and to judge whether he has the candor to say it out loud. But it’s not enough for a president merely to have a position. He has to have the skill necessary to follow through on his promises and translate his position into policy.

Another idea for improving campaigns is to focus more on the character of candidates, which may get us closer to understanding how they would operate in the Oval Office. That’s also a promising notion, but the way we end up judging candidates’ characters is pretty silly—by looking for press conference gaffes, dissecting the meals they ate when they were a young married couple, or assessing the way they play basketball.

So here’s a thought: What if we approached presidential campaigns the way a large corporation approaches its search for a new chief executive? The purpose of the campaign would be to test for the skills and attributes actually required for the job. Companies such as McDonald’s and Target do this even at the junior levels. Applicants are asked questions like “Tell us about a conflict at work you helped resolve” and “What’s the biggest obstacle you overcame?” The qualities employers are seeking are the same ones voters should be looking for in presidential candidates: initiative, experience, creativity, and problem solving.

Alas, when candidates are asked questions that might shed some light on these abilities, they run or dodge. They’re trained not to answer hypothetical questions and to tell only heroic tales about their past.

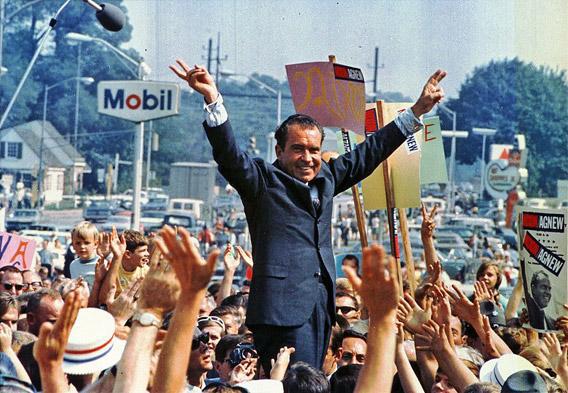

Ollie Atkins, White House photographer/Wikimedia Commons.

Well, nuts. That doesn’t mean we can’t try to ask these questions anyway. This series will look at the qualities a president actually needs to do the job as a way to better test for them during a presidential campaign. It’s hard to say which attributes are most necessary for a president, if for no other reason than we don’t know what he will face. It’s also hard to put your finger on how to measure certain qualities that will be revealed only under the pressure of a presidency. There is no training for the Oval Office. Still, we’ve got to do something with all of these television hours, rallies, and conversations with the neighbors, so consider four qualities to guide the way we evaluate candidates for the job:

Political skill: Campaigns give us a good idea of a candidate’s priorities, but can they read the political landscape they’ll face when they get to office? Are they honest enough to win voters’ trust but ruthless enough cut a deal with their enemies when necessary? Are they comfortable with the schmoozing, backslapping, and ego-massaging that comes with the job?

Management ability: Is the candidate focused enough to follow an overarching vision, but nimble enough to tweak that vision when real-world events intervene? Can they admit mistakes and learn from them? Can they sift through complex ideas? Can they recognize baloney when it comes from their staff or supporters? Do they know how to hire a good team?

Persuasiveness: Do they know how to deliver a good speech? Do they know when to stay quiet? Do they know how to read public opinion? Is it possible for a president to short circuit Congress by taking an issue directly to the people?

Temperament: Has the candidate ever faced a true crisis? Do they have the equanimity to handle the erratic and unpredictable pressures of the office? How are they with uncertainty?

You’ll notice a word that is missing here: leadership. We can all agree that a president should be a leader, but what does that mean? Gen. George Patton or Mahatma Gandhi? It depends on the circumstance. The word leadership in presidential politics only distracts or obscures. What a president’s critics really mean when they say he “isn’t leading” is that he hasn’t announced that he is supporting their plan. Challengers vow to show leadership, but that amounts to little more than saying they’ll magically pass the vast programs they’re promising. They don’t want anyone to ask the “how” question. They want you to assume that a leader can get anything done.

Rather than testing for leadership, we should recognize that leadership is actually the sum of these four attributes—and probably a few more. These attributes, unlike the vaporous leadership mantle, are more measurable qualities. We shouldn’t let politicians get away with asserting they have this magical ability when we can bore down a little deeper to see whether they have these necessary and underlying traits.

I am not claiming that by looking at things this way we can produce a mathematical formula for candidates. There is no Myers-Briggs test for successful presidents. But unlike the mindless speculation over who will get the nod to be a candidate’s running mate, at least thinking about these is not completely useless. In the end, searching for the answers should help bring the candidates into somewhat clearer focus.

And I hope you’ll pitch in to help me. Name your own attributes and email us at slatepolitics@gmail.com. Make your case for skills that are important and why you think so. I know you’ll also feel free to critique the reasoning in these articles, and I’ll write a follow-up article reframing my thinking based on the best input.

The end goal is not, nor should it be, a bleached contest drained of all drama. Different people will reach different conclusions about how much experience or management ability a particular candidate has, and one attribute may overshadow all the rest given the particular demands of the moment. The goal is to help us better think about the qualities these presidential candidates may actually need once in office. On Election Day, voters must take a leap. But maybe this exercise can help them see a little more clearly where we might land.