Ann Romney says that she and her husband call the rope line the “advice line.” Every time the candidate works the crowd, well-meaning supporters lean across the rope to offer tips about how he can improve his campaign. At fundraisers, donors give him advice on everything from sovereign debt to his speaking style (slow down!). Conservative pundits have been offering critiques by the wagonful for months.

Ignore or adapt? That is the question for the Romney campaign, which finds itself down in the polls, under siege, and with 40 days before the election. If Romney has a clear vision for righting the ship, then he must smile and ignore the chatter. This is a laudable attribute. Who wants a weathervane as president? When Hillary Clinton was ahead in the polls, Barack Obama resisted calls to panic. It was one of the first signs he might be ready to be president.

On the other hand, if circumstances have changed, Romney should take a gamble, scrap his plan, and adapt. Otherwise he’s going to blow his best chance to beat a weak incumbent.

Romney faces a management decision of presidential proportions right now. The decision over the direction of his campaign mirrors the constant tension a president faces—do I stick to my strategy or stop compounding the same mistakes? In the middle of a day swirling with other choices, a president must decide: ignore or adapt?

The way a presidential candidate manages his campaign tells us something about how he will govern. Vision, perseverance, risk-taking, and adaptation. These are all words from the corporate world where Mitt Romney made his fortune. Surely they’ve all been the subject of Harvard Business Review cover stories. But it’s much more than management-speak. A president can be the most gifted politician of his generation, but if he bungles this part of the equation his administration isn’t going anywhere. Just ask Jimmy Carter.

What is the most important management quality?

It can get very loud in the Oval Office. Congressional enemies and allies, the press, and the public all want to tell you what you are doing wrong. If there is one management quality for a president above all others, it’s the ability to ignore the noise. Make a decision and move on.

Nearly every chief of staff, top-level aide, and senior military officer I’ve asked says that decisiveness is a president’s most crucial attribute. Clarity from the top trickles down, which removes the possibility that the president will later get mired in some smaller skirmish to enforce his will.

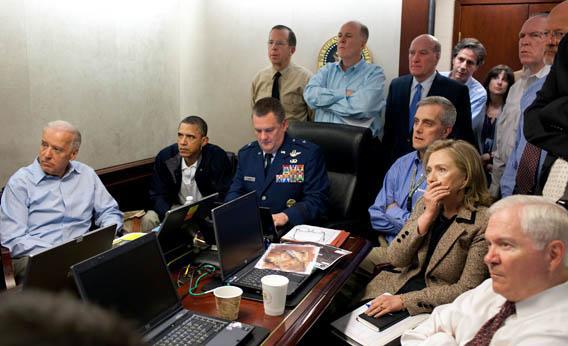

In interviews with military officials intimately involved in the operation to kill Osama Bin Laden, this decisiveness is the single quality they cite when asked open-ended questions about President Obama’s role: His ability to convey clarity both in the questions he asked and in his final decision. “Anyone who says that any other person could have made those calls doesn’t know what they’re talking about,” says one who was involved.

“The essence of the ultimate decision remains impenetrable to the observer,” John Kennedy said of presidential decisions. This means a president, like a candidate, must be highly skeptical of the kibitzer. Lack of information does not, however, slow the critics. The critic is booked on all three cable networks and must say something.

Never mind the many ways the critic can be wrong. Sometimes they are blind to context. (The president isn’t criticizing Saudi Arabia because the country’s ruling family is helping him with a covert action against Iran.) Or, the critic is blind to the political reality. (The public option doesn’t have the votes to pass and nothing will change that.) Or, the critic doesn’t realize that the president hears the complaints but is arranging things to make it look like he came to the idea on his own so he doesn’t appear weak.

Can you lead by doing nothing?

Usually the advice a president gets amounts to this: Do something. But there are times when leading means not acting. No matter what your reputation, critics will complain if you don’t immediately start barking emergency orders into the telephone. “He will be remembered, I fear, as the unadventurous president who held on one term too long in the new age of adventure,” presidential historian Clinton Rossiter wrote of Eisenhower. Apparently, you can lead Allied Forces to victory and people are still going to question whether you’re too timid.

These critiques are often unjust. Mitt Romney was an enormous success in business, turned around the Winter Olympics, and won his party’s nomination, but is still called a wimp for being risk-averse—in an age when excessive risk-taking arguably led to the financial collapse and some of the worst decisions in 11 years of war. Obama sent a surge of troops to Afghanistan, passed once-in-a-generation health care reform, and ordered the operation that killed Bin Laden, and yet the call goes up that, “We need a leader not a reader!”

Photo by Pete Souza/The White House via Getty Images.

Eisenhower should serve as a cautionary tale to presidential critics. While in office, he was derided as a distracted fellow whose biggest mark was the divots his golf shoes left in the Oval Office floor. But his presidential papers revealed that Ike was deeply involved behind the scenes. He was criticized, for example, for allowing a “missile gap” to grow between the United States and the Soviet Union. He knew from U-2 spy planes that no such gap existed, but he chose not to answer his critics for fear of inciting an even greater arms race. (To resist laying your critics low is an act of presidential temperament that we’ll discuss in the final piece in this series.)

Conservatives criticize Barack Obama for “leading from behind.” That’s a term used by an anonymous staffer in a New Yorker profile about Obama’s strategy in Libya, but it has grown into a laugh line at Republican rallies. It is supposed to show just how clueless the incumbent is about leadership. Leaders are supposed to clatter to the front, sword in hand, and lungs full of hot breath.

No.

“Leading from behind” shares similarities with the “hidden hand” that Eisenhower used so effectively. Eisenhower recognized that sometimes it was preferable for the president to work through others, as he did during the McCarthy episode of 1954. Publicly, Eisenhower said it was up to the Senate to discipline the reckless Wisconsin senator, but privately he guided the campaign that led to his censure. The task then, for those of us trying to evaluate leadership is not to immediately dismiss the style used, but to determine whether it is effective.

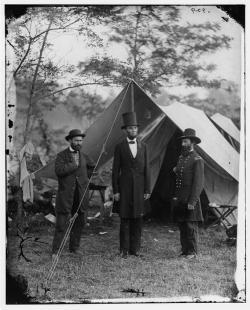

Whether a president chooses to act or not, strong leadership requires conviction and clarity. No presidential decision is easy, so all of them come with critics that must be ignored to keep an administration focused. Inside the administration, conviction and constancy (backed up by operational attentiveness) keep the bureaucracy from spinning out of control. In a possibly apocryphal story about Abraham Lincoln, the 16th president once called his advisers together to offer their opinions. When all disagreed with him, he said: “There are 12 against and one for and the ayes have it.” Lincoln’s team knew where he stood because he made it clear.

Photo by Alexander Gardner/Library of Congress.

Lincoln didn’t direct his administration by force alone. His famous appointment of a “team of rivals” thrived because Lincoln tended to them. He clashed with his secretary of state, William Seward, a former political rival who thought he knew better than the president. But as Donald Phillips points out in Lincoln on Leadership, the president’s constant and regular attention to Seward eventually turned him into an ally. “Executive force and vigor are rare qualities,” Seward wrote to his wife in 1861. “The President is the best of us.”

Jimmy Carter presents the opposite case. Surrounded by a group of Georgia loyalists, he lost control of his Cabinet and the vast array of bureaucrats that make up the executive branch. This was in part by design. The notion of a “Cabinet government” was in vogue in the late 1970s. So Carter declared a hands-off organization, where each Cabinet head had the autonomy to pursue his own goals. As James Fallows outlined in his essay “The Passionless Presidency,” his famous deconstruction of Carter’s failures, the delegation led to predictable clashes as Cabinet heads followed their own ambitions, not the president’s.

If various factions in an administration believe they can game the president, they will never carry out his wishes. This was the downside of Bill Clinton’s long, rambling all-night meetings, which one staffer described to Elizabeth Drew as a “floating crap game about who runs what around here.”

Mitt Romney has a well-earned reputation for ideological malleability on issues from abortion to gun control, but he also has an accomplished manager’s ability to stick with the game plan. On some issues, like the full release of his tax returns, he is immovable. Those who worked with him on the Olympic Committee in Utah say that the defining characteristic of his success was his tenacious discipline and focus. And those who have served with him in his church describe the same quality, going back to his days as a missionary in France. After a car accident there that killed the wife of the head of the mission and nearly Romney himself, the 21-year-old put his injuries and feelings aside and stepped in to lead the entire enterprise.

Name a time when you reversed course and why?

Fortitude can be a liability. Some of the greatest presidential mistakes—from the Bay of Pigs to the strategic failures of the 2003 Iraq war—were the result of holding fast to decisions long after the facts on the ground had changed. Writing about Kennedy’s blindness during the Cuban invasion, James MacGregor Burns describes “CIA experts who played to JFK’s bias for action and eagerness to project strength. The White House had no process for registering dissent, or for bringing in independent voices from the outside.” Arthur Schlesinger described a “curious atmosphere of assumed consensus.”

George W. Bush was known for his lack of flexibility, but even he knew how to adapt. After months of pursuing a losing strategy in Iraq, Bush adopted Gen. David Petraeus’ counterinsurgency strategy to turn around the course of the war. After heavy election losses for his party in 1994, Bill Clinton embraced Republican plans for welfare reform. Barack Obama dropped his opposition to the individual mandate to pass health care reform.

How a president determines to adapt to new circumstances is crucial to his management success. But in campaigns, we penalize adaptation. If a candidate changes positions, it’s called flip-flopping. The tolerance for mistakes and course-corrections is so low that the smallest verbal miscue becomes a “gaffe” that controls a news cycle. (Whenever you read this, I’m betting a “gaffe” story has either just broken or begun to die down.)

Campaigns not only obscure our efforts to measure a candidate’s ability to adapt, they actively weaken it. A candidate who survives a campaign has an overdeveloped “ignore muscle,” since he’s had to weather so much bad advice and silly non-controversies. For months, they have been coaxing campaign donors for cash, which puts them under a steady shower of advice from wealthy non-experts who are free to express their ideas any way they like.

When a candidate becomes president, they have to break out of that mode, because the plans they make for the next four years are going to be upended almost as soon as they take possession of the Oval Office bathroom key. As David Sanger reports, Barack Obama learned when he took over from George Bush that the United States was engaged in a secret cyber war against Iran. That reshaped his plans to engage the Islamic Republic. Bill Clinton’s early read of the economic conditions caused him to focus more on deficit reduction in his first term than the stimulus he had promised as a candidate. Obama also quickly learned that the financial crisis was much worse than he expected. If a president can’t plot midcourse corrections, it’s going to be a very long four years.

How do you think about failure?

As James Fallows writes, “The sobering realities of the modern White House are: All presidents are unsuited to the office, and therefore all presidents fail in crucial aspects of the job.” Given this truth, presidents would be wise to follow that maxim from Silicon Valley: fail fast. Otherwise, they’ll be stuck late in their administration with inevitably low approval ratings, the punishing requirements of getting re-elected, and the regret that they no longer have the room to maneuver that they once did. If they accept failures, they can learn from them and chart a new course while their administration is still young enough to act.

If we were really serious about looking for the best possible president during campaign season, we’d treat the candidates’ stumbles more intelligently. Rather than rushing to Twitter, we’d look to see how candidates recovered from their missteps and what they learned. Since we know that presidents will have to adapt to circumstances, sometimes fast (Reverend Wright! The 47 percent!), paying attention to these moments is one of our best opportunities to see if candidates can think on their feet. But by treating every slip-up like a hand-in-the-cookie-jar moment, we spook the candidates. There’s no upside for them to be candid with us about their mistakes, so they deny that they ever happened.

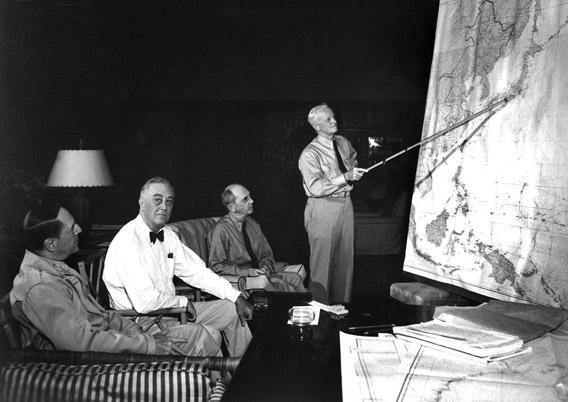

We obviously don’t want a chronic fumbler in office, but no one can be successful without having made some mistakes. If they’ve never made a mistake, it means they weren’t taking risks. And every president must take risks. This was one of FDR’s great skills. “Bold, persistent experimentation,” he called it. He was willing to try lots of things. Some failed and when they did, he learned and moved on. “I experimented with gold and that was a flop,” he once told a group of senators. “Why shouldn’t I experiment a little with silver?” Roosevelt wasn’t afraid of failure.

National Archives/Wikimedia Commons.

Mitt Romney and Barack Obama have shown us very little about how they handle mistakes and adapt. Obama says that his biggest mistake is that he didn’t tell better stories to explain where he wanted to take the country. Mitt Romney copped to the fact that he didn’t think Jet Blue was a good investment. These non-admissions are nearly useless for the purpose of evaluating whether either man has what’s required for the job.

For starters, Mitt Romney could tell us about the internal decision making that led to the Paul Ryan pick. That was a risk, picking the man with a paper trail who Democrats had tried to turn into a lightning rod for two years. It was a big risk, especially for the risk-averse “wimp” Romney. But campaigns resist talking about the real process that led to a decision. The only thing they want to be detailed about is the way Ryan sneaked out the back of his house to secretly meet up with Romney on the big day. If there was a little more honest inquiry into Romney’s thought process, voters may get a window into the inner workings of the man. With 40 days before the election, voters have no such window.

Newt Gingrich talked about the need for quick adaptation during his candidacy. He said he would create a public comment system to help him identify mistakes quickly and fix them. Newt proposed a networked “feedback mechanism” where supporters “can go online and say that say, ‘That didn’t work,’ or a mechanism for you to say, ‘Try this’ if you find something smarter or if the world changes and there’s a new problem, the sooner we talk to each other the better.”

This may be too unwieldy or zany. (Imagine the White House comments section: spoonboy343 says, “Yr Fed pix suk!”) But at least Gingrich had a theory about how he would run his White House. Most presidential candidates end up in Kennedy’s dilemma: “I spent so much time getting to know people who could help me get elected president,” he said, “that I didn’t have any time to get to know people who could help me, after I was elected, to be a good president.”

What’s the most important quality in a staffer and why?

A president can build adaptation into his White House staff. President Obama’s former chief of staff Rahm Emanuel says that the most important quality a staffer can have is candor. They’ve got to be able to tell the president he is wrong, because the president is entombed in flattery. The halls are filled with your picture. Movie stars blanch in your presence. People talk about you in whispers.

George W. Bush used to tell the story of what it was like to eavesdrop on staffers or members of Congress sitting outside the Oval Office. When they were on the outside, they’d talk about how they were going to give the president a piece of their mind, but once they crossed the threshold, they were only able to compliment the president on his tie and tennis game.

Knowing about the perils of sycophancy isn’t sufficient to insulate your presidency from groupthink. (Otherwise, George W. Bush would have short-circuited a few problems.) When President Obama came into office, he said he was reading Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book Team of Rivals, about Lincoln’s Cabinet of tough competing personalities. It was meant to show that he understood there needed to be competing viewpoints in his administration to keep the thinking fresh. This is also what Michael Kranish and Scott Helman describe in The Real Romney as “the Bain way.” According to the authors, Romney always wanted as many smart minds in his inner circle as possible to ensure a competition of ideas. When there wasn’t sufficient argument, he would take up the role of devil’s advocate himself. Or, as Romney put it to a small group of Iowa businessmen during the primaries: “I am a capable enough business guy to know when people are blowing smoke and when they’re not.”

But the rivals can get out of hand. Obama had never run anything beside his campaign team. He had no experience managing an unruly group of egos who had not been with him in the campaign trenches and who lacked the deep personal loyalty that created. By several accounts, his inexperience contributed to the messy and backwards economic policy process. One of those accounts came in a memo from one of Obama’s top advisers, as reported in Ron Suskind’s book Confidence Men:

First there is deep dissatisfaction within the economic team with what is perceived to be [Larry Summers’] imperious and heavy-handed direction of the economic policy process. Second, when the economic team does not like a decision by the President, they have on occasion worked to re-litigate the overall policy. Third, when the policy direction is firmly decided, there can be consideration/reconsideration of the details until to [sic] the very last moments. Fourth, once a decision is made, implementation by the Department of the Treasury has at times been slow and uneven. These factors all adversely affect execution of the policy process.

The fact that this memo exists suggests Obama has someone on his staff who can give him bad news. Aides say that Joe Biden and David Plouffe play this role sometimes. It’s not entirely clear who can talk Mitt Romney down from a position. “He doesn’t listen very well,” said one GOP wise man who has spoken extensively with the candidate.

How do you know what you don’t know?

Mitt Romney may be the best-equipped candidate in history to enter the presidency. When a new president comes from the party out of power, it is always a turnaround operation. Romney has done that before. That was part of his job as a venture capitalist. He describes the analytical challenge of analyzing a new company, examining its component parts, and finding a solution to make it work better with the glee of a weekend tinkerer in a recent Bloomberg Businessweek interview. He put those skills to use in managing the Salt Lake Olympics, which he took on midstream. One ally likened his efforts to save the Winter Games to “putting together an airplane in midflight.”

Choosing the right staff for the moment is crucial, and a president is hampered by the hangover from his campaign. To pick his staff, a president starts with a long list of donors, party regulars, and campaign staffers expecting to go to the show, but those may not be the right people for the job. Noam Scheiber argues persuasively that President Obama’s initial staff choices for his economic team, picked in the crisis moments of his early presidency, circumscribed his ultimate policy options and led to a far more Wall Street-friendly economic policy. For an administration, your staff can be your destiny.

Mitt Romney has more experience than most other presidents in knowing how to pick and manage a team. He built management teams again and again with the companies in which Bain invested.

When he was a governor, Romney cast a wide net beyond his party. He turned to people like Robert Pozen, a former top executive at Fidelity Investments and Douglas Foy, the longtime president of the nonprofit Conservation Law Foundation. He gave them autonomy, but never too far beyond his reach. His first presidential campaign was different. Riven by factions, it lacked an overall strategy—Romney switched from being a competent Mr. Fix-It to a conservative ideologue and back again. Advisers clashed with no clear direction from the candidate.

Romney also has something Obama lacked: networks. People joke that he knows the owners of NFL and NASCAR teams, but his age and experience give him access and association with people from a variety of backgrounds. He knows more people than Obama did, people who bring valuable experience. When Obama came to the Senate, he had a tight-knit group of close associates, but he lacked a wide group of talented friends like Bill Clinton or George H.W. Bush.

Whether Romney listens to or seeks those outside voices is another matter. Neither Obama nor Romney are the most gregarious and approachable of politicians. They are, like many men of accomplishment, difficult to convince they are wrong.

The model again is Lincoln. Phillips describes how Lincoln managed to constantly fertilize his thinking by practicing the technique of “management by walking around.” He dropped in on Cabinet officials without warning, visited the troops and his generals, or simply talked with his fellow citizens. In 1861, he spent more time out of the White House than in it, and Lincoln’s personal secretaries reported that he spent 75 percent of his time meeting with people. When he relieved Gen. John Fremont of his command of the Department of the West, Lincoln wrote, “His cardinal mistake is that he isolates himself, and allows nobody to see him; and by which he does not know what is going on in the very matter he is dealing with.”

It would be hard for the modern president to collect outside views the way Lincoln did because presidents just don’t have much time. According to a senior Bush aide, when Barack Obama spoke to the outgoing president on the day of his inauguration, he asked if he could call on Bush for advice if needed. Bush said he would be happy to take the call, but that Obama would not lack for advice and probably wouldn’t want or have time to hear yet another voice.

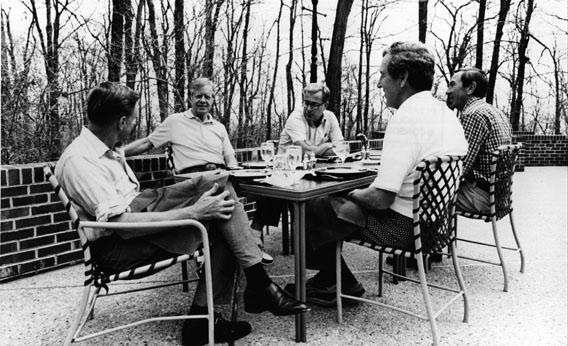

Jimmy Carter took this quality too far. In July 1979, his administration adrift, he spent two days at Camp David interviewing a host of invited guests about what he was doing wrong as president. He took notes on a legal pad. It became the basis for his “malaise” speech which, along with the mass firing of his Cabinet several days later, was a political disaster that sapped his power and made his presidency look rudderless.

Photo by Keystone/CNP/Getty Images.

Carter was trying to reinvigorate his administration in midstream. Romney would face a different challenge. Having promised so much, if Romney wins, he will need to get up to speed fast. Obama will need to find a way to keep up the pace. How will he create innovation in an administration where people, including the president, are set in their ways? How will he avoid the scandal that often drags down a president’s second term? He’ll have to turn around his administration immediately to face a new set of challenges. Perhaps he’ll bring in fresh eyes to look at how he’s running things and suggest a new course. After beating Mitt Romney, he’ll need someone with his management experience.