In 1832, horse racing was by far America’s most popular spectator sport. So when horses named Andrew Jackson and Nullifier appeared at the same racetrack in Richmond, Virginia, thousands of people saw their sporting and political interests overlap. The horses’ names reflected the most divisive political debate of the year, a constitutional crisis over “nullification.” At issue was whether the state of South Carolina could refuse to abide by a federal import tax backed by President Andrew Jackson. The situation was so serious that Vice President John C. Calhoun soon resigned his post and returned home to South Carolina to help mobilize troops in anticipation of a federal invasion. On the racetrack, at least, Jackson won and Nullifier lost.

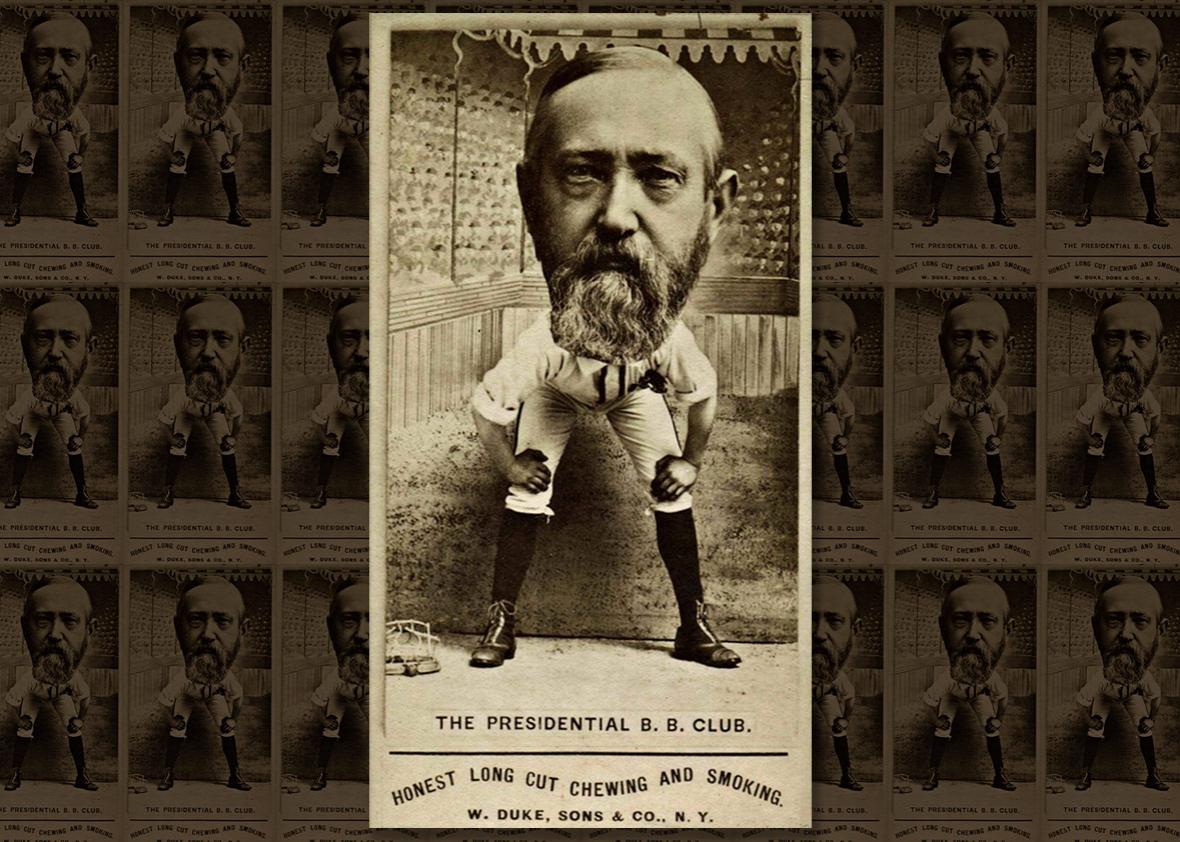

Whatever you might think about President Trump’s recent crusade against activist athletes, the idea that sports should be divorced from politics is a relatively new one. We can scarcely imagine a football game now between, say, the Tax Cutters and the Bernie Sandersites or an NBA matchup featuring the Golden State Liberals and the Indiana Conservatives. Yet explicitly political sports were the norm in American life for the nation’s first 125 years. At least two other competitive racehorses carried Jackson’s name in 1832, and past races had featured horses named for all sorts of politicians and parties, such as when “Anti-Democrat” and “Little Democrat” graced the same track in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in the first decade of the 1800s. Jackson himself once pitted his fighting cocks against those of a rival political faction as part of a July Fourth celebration outside Nashville, Tennessee.

The current debate over sports and politics has largely ignored this early history. Black American athletes were not the first to politicize sports when they made it a stage for protest during the 20th century. In fact, white men had used sports to rally political support since before the American Revolution. It was only in the early 1900s—when black athletes threatened to harness this tradition—that divisive politics were stripped from American sports.

As early as the 1750s, candidates used the popularity of sporting contests to mobilize voters. We like to think of the founding generation as model citizens, but eligible voter turnout was frequently at or below current levels, both before and immediately after the American Revolution. As a result, George Washington supplied alcohol to election parties where all sorts of games were common, and Thomas Jefferson curried favor by sponsoring shooting contests. When Charleston, South Carolina’s artisans wanted to oust wealthy merchants and planters from their local assembly in 1768, they organized their own horse races so that the elite Jockey Club no longer had a monopoly on the sport’s political influence. Efforts to mobilize voters through sport sometimes proved explosive. A 1770 cockfight between Revolutionary patriot Timothy Matlack of Philadelphia and a Loyalist New Yorker, James DeLancey, ended in a brawl that carried more political overtones than today’s Phillies-Mets melees.

Politicians used the competition and aggression at the heart of sports to appeal to the manliness of voters. Back then, it was mostly men who sought camaraderie and an opportunity to prove themselves through sporting competition. As an issue of the New-Yorker magazine put it in 1838, not participating in sports had social costs because “a refusal to do so subjects you to the taunts and jeers of those around.” Not coincidentally, of course, voting and office holding were largely restricted to white men during this period. By linking the manliness of sports to politics, candidates urged their fellow citizens to join the political fray for the same reason they needed to follow sports: to prove their place in society by picking a side in a heated competition. White men asserted their status not just by voting and naming racehorses after candidates but by betting on elections and brawling at the polls on an unprecedented scale, turning politics into what one commentator called “Sport for Grown Children.”

Campaigns and sports became so closely connected that Americans began describing elections as “races,” a turn of phrase that uniquely arose in the United States during the 1810s and 1820s. In contrast to the British, who still “stand” for election, the American notion of running and racing for office reflected American voters’ growing expectations that candidates actively compete with each other and personally solicit voters. It had been enough for Washington to throw a party in the 1780s, but by the 1820s, Jackson had to set up cockfights and travel around exhibiting his battle scars to demonstrate that he was man enough for the presidency. Even debates were cast as “spouting matches,” in an effort to attract participants to something that buried the boring “speechifying” of politics inside a shell of more exciting sport.

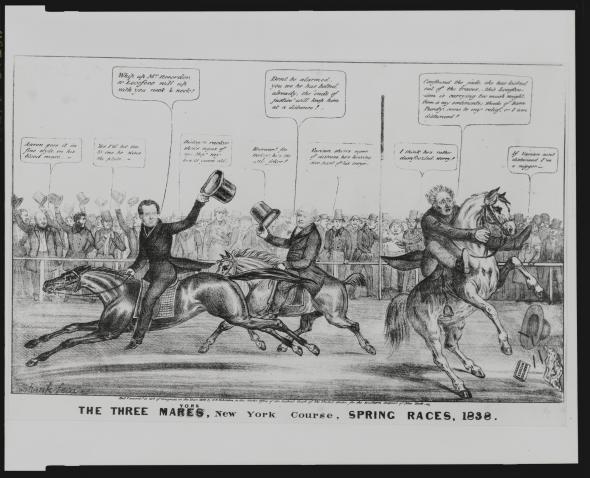

Library of Congress

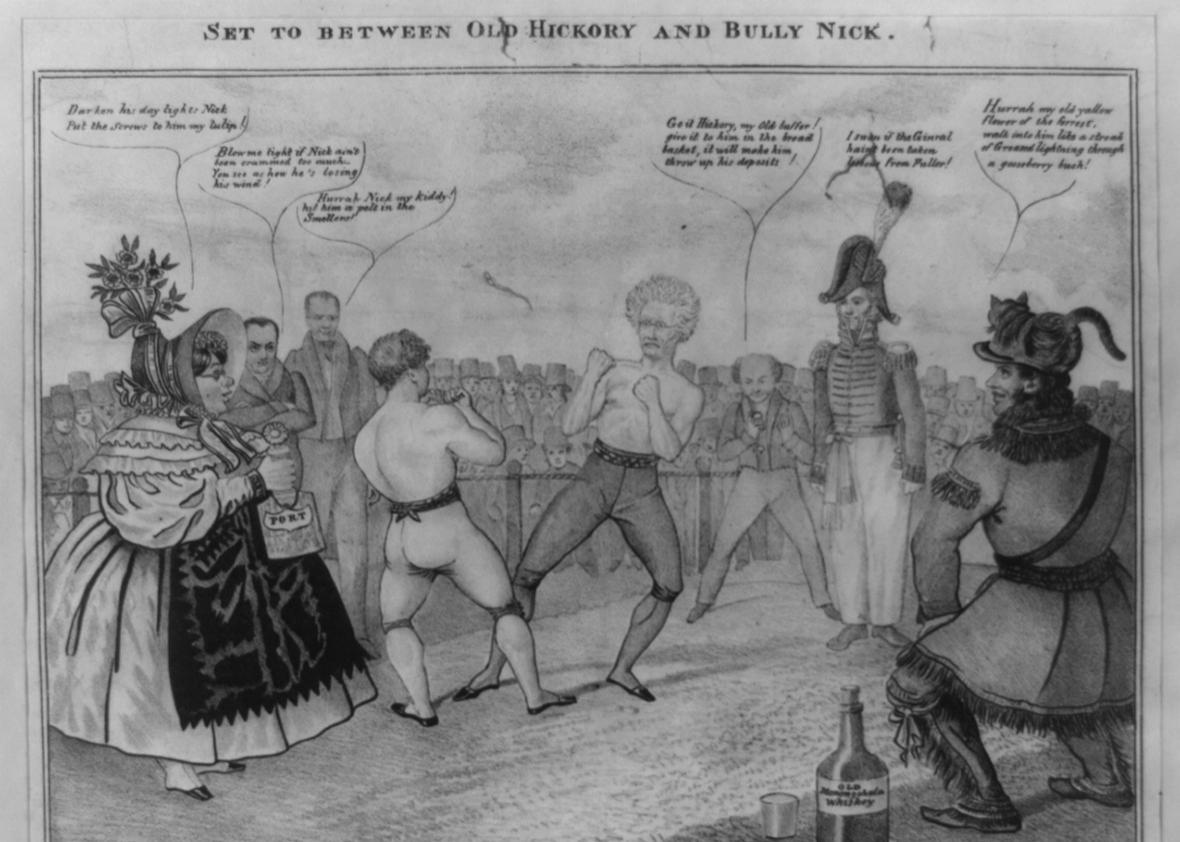

By the 1830s and 1840s, campaign cartoons pictured candidates as entrants in horse races, footraces, boxing matches, and card games, appealing to the white male electorate by couching policy positions in sporting terms. In the example seen here, New York City’s 1838 mayoral election is cast as a horse race with the radical “locofoco” candidate (a short-lived faction of disaffected Democrats) portrayed as unsettling to his mount. Meanwhile, the crowd of white men—whose varying clothes and hats suggest different social classes—comments on the radical candidate in racist terms. Casting the radicals as sporting losers made them less appealing to voters while erasing and denigrating black Americans (despite their actual presence at most racetracks) made clear that politics was a sport for white men only.

The politicization of sport was part of a larger effort to make politics fun. By the 1840s, partisan theater, parades, and carnivals joined with sport to mobilize eligible voters at the highest rate in American history, with 70 to 80 percent casting ballots.

The Civil War is often cited as the moment when national unity became the political goal of sports. “The Star-Spangled Banner” was famously played before a ballgame for the first time in 1862, and historians often note the instances when Northern and Southern soldiers played baseball together. But much more common were the boxing matches that reflected the era’s political and ethnic factions. Irish-born champion John Morrissey rose up through the Democratic ranks by representing the party in fights and eventually won a seat in Congress in 1867, the first sports star to achieve national office.

Library of Congress

It was only after the war that the relationship between sports and politics began to change. Black Americans had made up a large percentage of the early republic’s jockeys, boxers, and sports fans, although they had never been permitted to make explicitly political statements at sporting events. But after the Civil War, black stars and fans had (at least nominally) many of the same rights as white men, including the right to vote. In the decades following the war, ballplayers like Octavius Catto, jockeys like Jimmy Winkfield and Jimmy Lee, and boxer Jack Johnson made white men worry about how black athletes might channel their popularity into politics. If everyone wanted to “pat the back of this ignorant colored lad”—as one writer described a mob celebrating Jimmy Lee in 1907—then the old politicization of sports suddenly presented a new threat to the racial order. As another correspondent put it, sporting environments needed to dissuade black men from politicizing sports so that they “did not strut about the lawns to pre-empt the good seats in the grand stand or go about the resorts of white men flaunting loud stripes and checks and the fifteenth amendment” that granted them voting rights. For many white Americans, sport was no longer an amusing way to drum up votes once it promised to mobilize those who did not share their Northern European heritage.

A fear of black political power gave new urgency to a reform movement that had been trying for generations to separate politics from sports. As far back as the colonial period, critics had warned voters of being “bribed, or drammed, or frolicked, or bought, or coaxed, or threatened out of your Birthright [to vote].” Those warnings suddenly gained traction at the turn of the 20th century, as a string of corruption cases and a growing pool of black and immigrant voters scared many middle-class Americans. The result was a wave of legislation that outlawed gambling on elections, banned alcohol sales near polling places, instituted the secret ballot, and enacted more stringent voter registration. For better and worse, these changes sobered the experience of American politics and greatly reduced voter turnout.

As political events became less sporting, sporting events became less politically divisive. Without politicians and parties driving the sporting experience, entrepreneurs embraced celebratory nationalism. By the 1910s, partisan brouhahas had evaporated almost entirely from sporting events. Elected officials began to throw out first pitches instead of campaigning on baseball cards. Games became a place for honoring office holders rather than arguing about who should be in office. This was the era when “The Star-Spangled Banner” began to be played regularly before sporting events, beginning with a 1918 World Series game in Chicago—one day after a federal building there had been bombed, allegedly by immigrant anarchists and labor activists. National pride and order replaced disorderly political division only once blacks and immigrants became political forces to be reckoned with.

The effects were particularly pronounced for black athletes and fans. Promoters kicked black men out of top competitions in order to placate white audiences and competitors in both the North and the South, and decades passed before black American athletes returned to mainstream professional American sports. By the time they did, most Americans had forgotten that sport had once been accepted as a political battleground. The rules of the game were changed just when black Americans began to truly play, and in many ways are still being held against them today.