In a dizzying series of tweets and news stories on Monday, the Pentagon appeared to simultaneously embrace transgender recruits while the Trump administration was losing its bid in court to deny their entry into the service. Once the dust settled, it became clear that, for now, the slow policy change on transgender service that began under President Obama will continue under President Trump. Transgender people who want to serve their country in uniform may enlist starting on Jan. 1; those now serving can continue, with appropriate support from the military’s medical and personnel systems. Far from being a military coup, this was merely a case of the Pentagon following existing law while the courts haggle over what exactly the law is.

That fact may itself be startling at a time when senior administration officials seem more willing to unlawfully promote their boss—or misuse their offices—than follow the law. The Pentagon chiefs’ response to the transgender litigation illustrates how they differ from other senior officials, for better or worse. In response to Trump, the military’s leadership has improvised a new norm of civil-military relations: something in between a yes and a no that doesn’t amount to insubordination but does help modulate Trump’s excesses.

Although civilian Cabinet officials, generals, and admirals are all “Officers of the United States” under the Constitution, appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate, they have very different traditions of service. Over more than 240 years, but especially since World War II, the military has evolved into a profession that puts a premium on apolitical service to presidents of both parties. Senior military officers serve tours in key positions that are staggered so that they transcend administration boundaries. Senior officers and junior troops alike are bound by military justice provisions and regulations that sharply curtail their political activity. By rule, custom, and inclination, today’s military leaders shun direct involvement in partisan politics, such as standing on stage during rallies, even at the request of their commander in chief. Those officers who do politick for the boss—like Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster writing a controversial op-ed supporting Trump’s “America First” policy—stand out as conspicuous exceptions to the rule.

The policy on transgender service has taken a convoluted path akin to an Army land-navigation course. Whether Trump likes it or not, things stand now as they would have had he never tweeted his demand for a trans ban in July. Pentagon leaders delayed implementation of Trump’s tweet, seeking clarification, and then set in motion the slow, grinding machinery of bureaucracy and litigation. The yearslong process begun in 2016 by then–Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter will continue moving toward its logical conclusion: open service of transgender troops. Unless Trump’s Justice Department convinces a higher court to overrule two lower court injunctions, the military will continue to include thousands of transgender troops who serve today and thousands more who will volunteer in the future at disproportionately higher rates than the population at large.

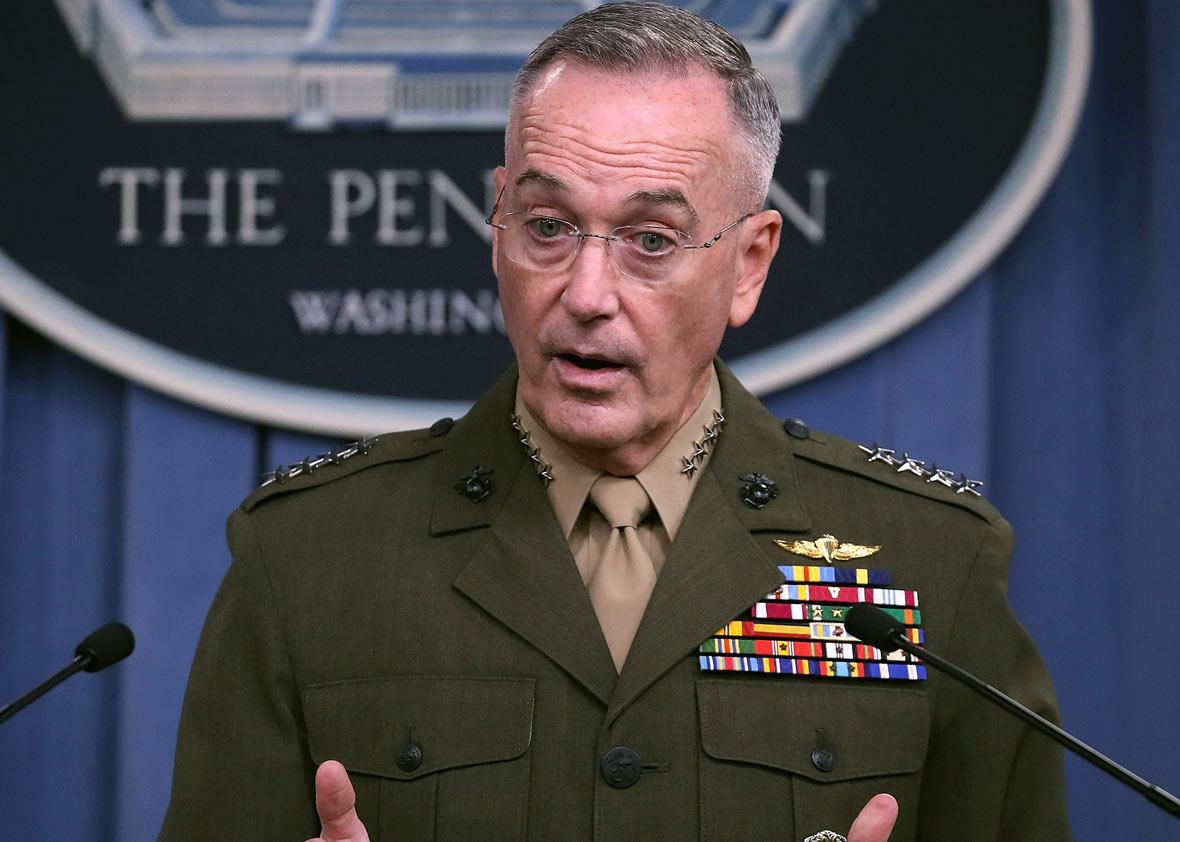

In this, as in other cases, like the public debate over racism after Charlottesville, military leaders have struck a posture that’s not disloyal but still allows the ship of state to correct its course when steered in the wrong direction by an errant president. It is significant and telling that the highest-ranking military officers—such as Gen. Joseph Dunford, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the four chiefs of the armed services—did not file affidavits in support of the government in the transgender cases. The government relied instead on a handful of unpersuasive affidavits of midranking uniformed officers and senior Pentagon civilians. It’s unclear how much the generals’ prestige would have affected the cases’ outcomes—especially at this early stage, where the facts are less of an issue than the law. However, District Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly signaled in her opinion that the government failed to persuade her that the military was as concerned about this policy as Trump was. “In short,” Kollar-Kotelly concluded in her October opinion, “the military concerns purportedly underlying the President’s decision had been studied and rejected by the military itself.”

If senior military leaders truly stood with Trump on the trans ban, they might have distanced themselves from the studies referenced by the court that suggest allowing transgender troops will have few costs and minimal impacts on military readiness. Defense Secretary James Mattis did so to some degree early on, although he merely said he wanted more rigorous evaluation, not different results. Similarly, military leaders like Mattis, Dunford, or the four-star officers responsible for recruiting, training, and maintaining the services could have averred that the Obama administration was wrong or that there were tangible readiness impacts from the new policy that Trump was right to fix. That none of these senior military leaders did so speaks volumes.

Make no mistake: This is not defiance and does not foreshadow a military coup. Rather, I think we are seeing military leaders doing their best to navigate complex and sometimes conflicting legal imperatives while also preserving the professional (and necessarily apolitical) ethos of the all-volunteer force. The service chiefs cannot march in step with a president who fawns over violent extremists at Charlottesville while simultaneously maintaining good order and discipline within their ranks. Likewise, military leaders cannot simultaneously salute the president on transgender policy while saying the Army’s “greatest asset is our people” and the Army is “indivisible.” The service chiefs know, based on their manpower and recruiting numbers, that they can ill afford to publicly champion a policy that shrinks the eligible pool of qualified recruits, especially at a time when they are seeking to grow their ranks.

Call it respectful disobedience or selective engagement or lawful resistance or some other euphemism—but it’s clear that military leaders have found a formula for saluting their commander in chief while keeping his worst excesses at bay. In this, they are probably aided by a secretary of defense and White House chief of staff who have literally worn their shoes. Jim Mattis and John Kelly may not be able to moderate the president’s worst statements or most egregious tweets, but they almost certainly provide cover for senior military leaders behind closed doors, where they can explain to the president why the generals are behaving a certain way.

This provides a reason to be optimistic. On issue after issue, there seems to be a gap emerging between the president’s first (and often outlandish) statements and the policy that eventually emerges downstream. Perhaps the military leaders have correctly intuited that Trump’s initial positions are simply an opening bid in negotiations. Or perhaps these leaders have learned behind closed doors that they can, in fact, stand up to Trump. Whatever the logic, this dynamic can apply in a broad array of fronts, from reducing the risk of war with North Korea to refining immigration policy to better support of military recruiting—and may just end up saving the republic.