The video is said to be graphic. Taken by an officer’s body-worn camera, it apparently shows a man crawling toward the officer, looking confused. The man makes a “quick movement”—maybe it’s a move to pull up his shorts, maybe it looks like he’s about to pull out a gun—and the officer shoots him to death.

Those of us who weren’t in the Arizona courtroom the day the body camera video was played for the jury can’t assess either man’s behavior. That’s because the judge in Mesa police officer Philip Brailsford’s second-degree murder trial agreed with the defense that the media should not be allowed to see the video of Brailsford killing Daniel Shaver. While part of the bodycam footage was released last year, the Mesa police edited out the footage of the actual shooting. In his ruling last month, Judge George Foster agreed that the media should not get its hands on the full video evidence, even though the videotape was central to a case of intense public concern and was shown in open court. The Arizona Republic reported that the judge said that “the video could anger the public and also ‘serves as turning a burning ember into a flame.’ ” Brailsford’s trial is ongoing.

You might think police bodycam footage is a public record and therefore should be accessible to the public. That first part is mostly correct. Police-created videos help “document governmental activities, decisions, and operations” and, therefore, should be considered public information. That’s language written by the Ohio Supreme Court in a police dashcam case.

But not all public records are instantly accessible by anyone who wants to see them. There are privacy reasons, police investigation reasons, and fair trial reasons among others to keep certain documents, photos, or videos out of public hands at certain times. The Arizona judge’s statement about the video causing public anger suggests he’s mostly worried about the footage’s potential to cause harm, given the reach of today’s media.

There is precedent for these sorts of concerns. In 1992, the highest court in Texas boasted that it had kept an embarrassing sex videotape shown in court out of the hands of a requesting tabloid television show. A Florida court in 2005 suggested it would keep death photographs from a high-profile murder case off the internet to help protect the family from the emotional turmoil that would result from such publication. “We can well understand that the family does not wish to have these photographs published in the press or on the internet,” the court wrote, “no one intends to let that happen.” In 2016, an Alabama federal court mentioned “public ridicule” as a reason for its decision to keep juror information secret. And a California court in 2010 described what had happened in a case in which state employees circulated gruesome photos of a teenager who had died in a car accident: “the photographs were forwarded to others, and thus spread across the internet like a malignant firestorm, popping up in thousands of websites,” leading “internet users at large” to taunt surviving family members “in deplorable ways.” The court found that such dissemination would support an invasion of privacy action filed by the teen’s family.

Taken together, as sympathetic as the individuals in these cases may be, those decisions and the accompanying rhetoric do not bode well for public access to government documents and freedom of information. In the Arizona case, we’ll likely see the video footage as soon as the trial is over; the officer’s attorney has argued it should be kept from public view only until acquittal or sentencing. We likely won’t, however, see much footage from bodycams of other police officers facing similar confrontations. An article last year in Communications Lawyer listed multiple new state laws regarding access to police body camera footage. The majority of these laws give much greater weight to keeping such videos out of public hands on privacy and police investigation grounds and much less weight to interests in government transparency and public understanding of government activities. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press maintains that access to such videos today is a “challenging endeavor” for journalists despite the news value inherent in at least some of them.

Consider that a New York trial court last year offered five reasons for strong editing in response to a journalist’s request for access to police body camera footage even as the court noted that “the public is vested with an inherent right to know and that official secrecy is anathematic to our form of government.” Among those reasons: “Where the footage pertains to an incident that subjects a police officer, firefighter or corrections officer to discipline” and “Where the footage … would otherwise constitute an unwarranted invasion of privacy.”

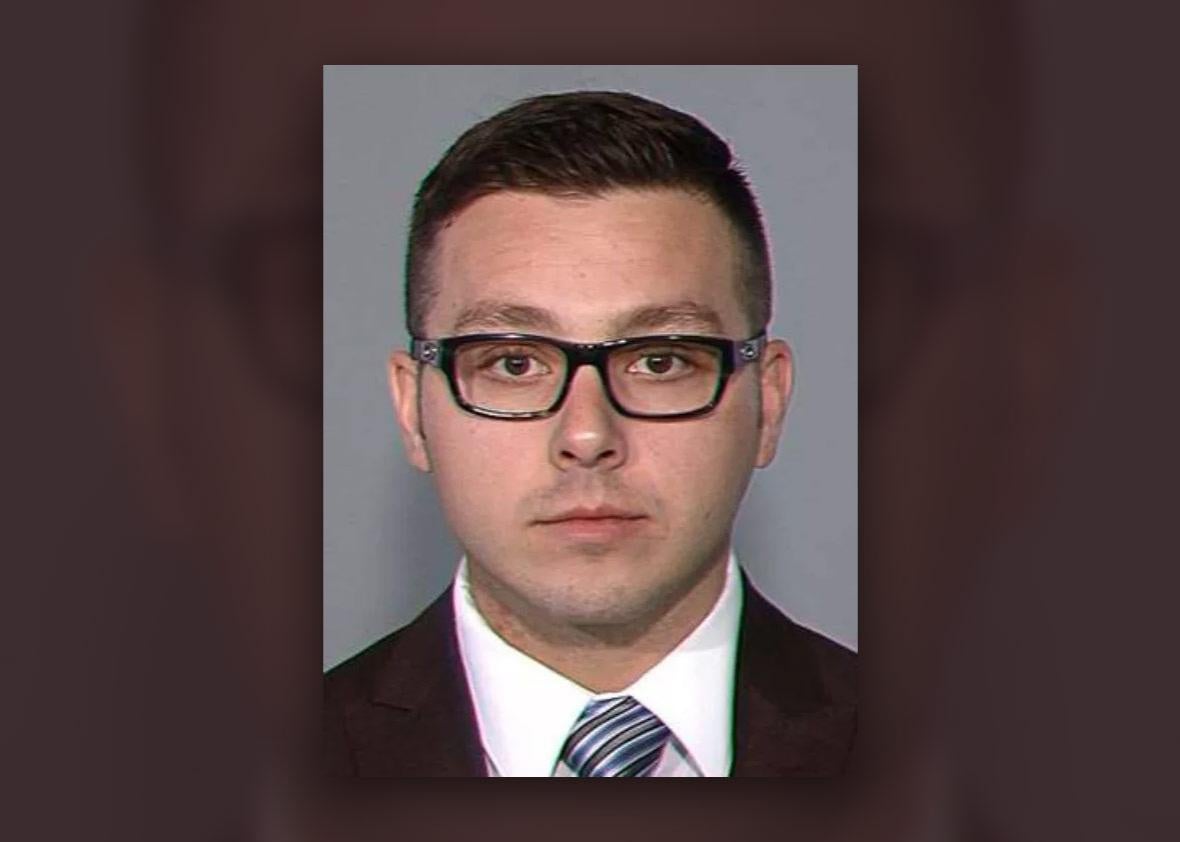

The pushback against access to public information extends beyond bodycam footage. Last year, a federal appellate court that was hearing a case brought by the Detroit Free Press ruled that arrestees’ mug shots—even those involving police officers charged with bribery— could be withheld from the public. That court joined all other federal appeals courts in deciding that people had a privacy interest in their booking photos, worrying specifically that “websites collect and display booking photos from decades-old arrests” and that such internet publications could hamper individuals’ job prospects. There, individual privacy interests trumped the public interest, even though police routinely give the media access to mug shots, and even though journalists have argued that those images can help provide evidence of police brutality and other newsworthy information. The court, though, based its decision not on public interest in the information but on what might happen to the information once it’s released.

It wasn’t always this way, at least on paper. Many freedom of information laws include a presumption of public access to government material. The Illinois Freedom of Information Act, for example, suggests that “[a]ll records in the custody or possession of a public body are … open to inspection or copying” by the public. The law has since been amended to provide for numerous exceptions, with police body camera footage among the newest.

Add to all this the assessment by experts that the Trump administration, led by a president who refused to release his tax returns, is keeping more things from public access than the Obama administration, which in turn kept more things secret than did the Bush administration. We seem to know ever less about the government even as technology gives us the ability to know increasingly more.

These court decisions and this sort of anti-access language and procedure will likely affect what we’ll be able to get our hands on far into the future. When courts decide questions of public access, they at times ask whether the information at issue has traditionally been accessible to the public. If the law keeps bodycam footage, police mug shots, and much more out of public hands, information the public might well find valuable will be inaccessible until long after its incendiary potential—and its news value—has waned, conceivably forever.

The judge in the Arizona case has precedent on his side. Many appellate courts have held that the trial court judge has great discretion to decide what evidence might affect the defendant’s right to a fair trial. Then again, there’s a federal trial court decision from 2003 in which the court allowed “gruesome” evidence, including a 911 call, to be copied by the media over defense arguments that it would inflame public passion, thus pressuring jurors to vote for the death penalty. There, the court relied on the public’s presumed right of access to recordings admitted as evidence, giving more weight to informing the public than to defense worries about a fair trial. And there’s a recent New Jersey case that allowed press access to dashcam footage of a police shooting, suggesting that “the public’s powerful interest in disclosure” was paramount.

But many of the newer cases and newer statutes do not lean that way. The Arizona judge’s apparent eagerness to keep a very newsworthy tape away from the public, at a time when public interest is highest, continues a trend toward keeping information involving public servants away from those who pay their salaries.