As you read various articles about the twin tax plans offered by the House and Senate in the past couple of weeks, here’s one not-minor detail to keep in mind: Neither bill, as written, can pass Congress.

I’m not talking about vote-counting issues, a wholly separate field of land mines. At least with votes, arms can be twisted, side deals cut, and so on. I’m talking, instead, about the rules. The inflexible, intractable rules. Both bills would violate those.

The Byrd rule governs what’s allowed under reconciliation, the budget process that allows the Senate to consider bills not subject to a 60-vote filibuster. This rule, among other things, bars bills that would increase the deficit outside of the 10-year budget window. In other words: The tax reform plan, if it’s to be passed with a 50-vote majority in the Senate, could not increase the deficit in 2028.

Though an official public estimate of the effects in 2028 and beyond hasn’t been released yet, it’s clear enough that both the House and Senate bills would not only increase the deficit by then, but flagrantly so.

The last estimate of the House bill from Congress’ official number-cruncher, the Joint Committee on Taxation, projected that it would increase the deficit by $88.9 billion in 2025, $121.8 billion in 2026, and $155.6 billion in 2027. As you can see, those numbers are nowhere near budget neutrality—and they’re trending in the wrong direction, too. This plan would definitely increase the deficit in 2028.

The somewhat more generous Senate bill is even further away from its marks. It increases the deficit by $127.1 billion in 2025, $167.3 billion in 2026, and $216.7 billion in 2027. Follow that trend line and predict 2028. Rules would prohibit it from passing with 50 votes.

So what, you may be asking, are they even bothering with here?

Republicans have a few options for getting around this problem. One option would be to start from scratch and write new bills that don’t egregiously violate the rules or to throw in some massive revenue-raisers that would bring in hundreds of billions of dollars per year. Don’t count on it.

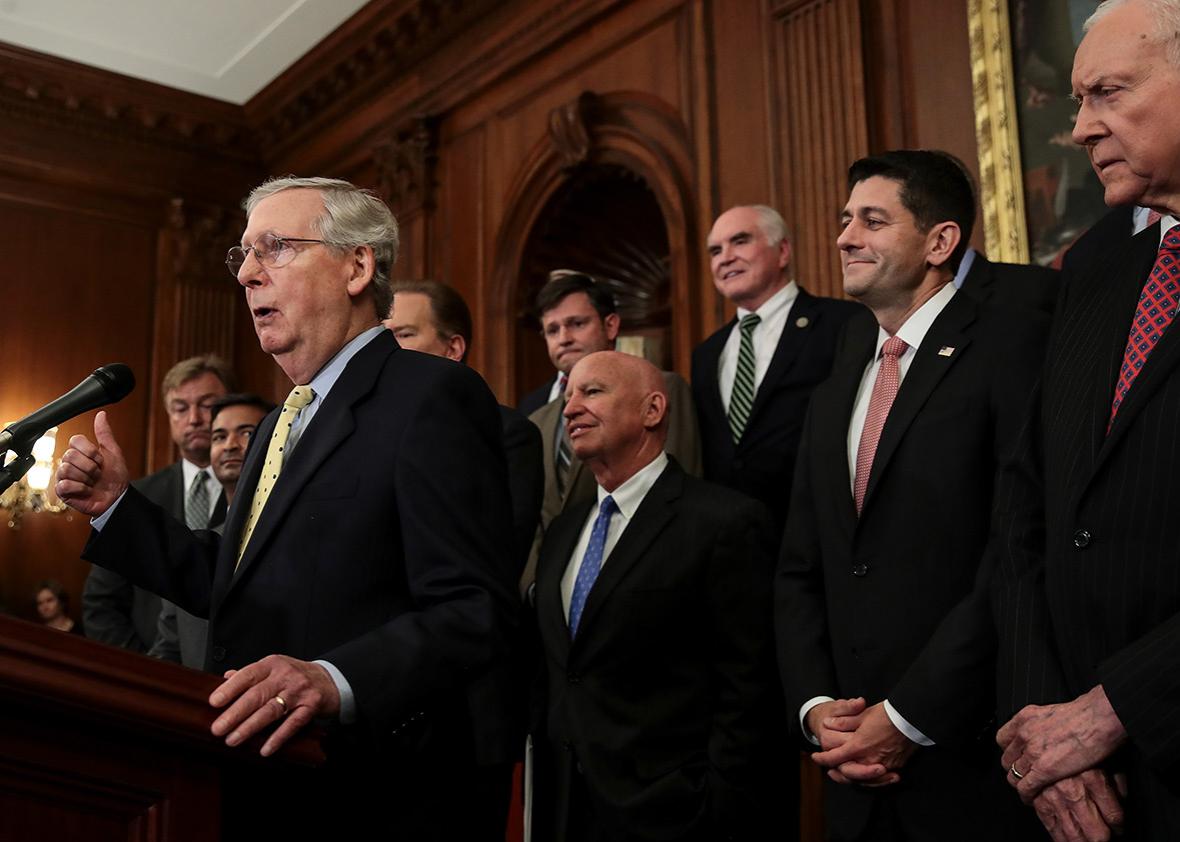

Another would be to play one of several parliamentary games that effectively would amount to killing the Senate filibuster, thereby allowing the Senate to pass whatever it wants with 50 votes. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has been unequivocally against such moves, though. And even if he did have a sudden change of heart, it’s unlikely he could bring the rest of his conference along with him.

Instead, Republicans will likely rely on gimmickry to ensure the plan that eventually passes the Senate complies with the rules. The overarching gimmick in these situations is to “sunset,” or eliminate, certain provisions after a number of years and then bank on Congress renewing them in the future. Think of the Bush tax cuts, also passed through reconciliation, which sunset after 10 years. Its authors knew that there would be major political pressure on Congress to renew at least its middle-class tax cuts. They were correct.

There’s already an element of this practice in the House bill. In order to get its bill in compliance with another budget rule—that the bill could only increase the deficit by $1.5 trillion in the first 10 years—the Ways and Means Committee chose to sunset a new $300 family tax credit after five years. House Republicans argue that we shouldn’t believe the law they’ve written, and that there’s no way a future Congress would allow those credits to expire. You can decide whether to believe that or not.

If Republicans ultimately followed this model to get their final product in compliance with the Byrd rule in the long run, they would have to sunset a lot of the popular individual tax cuts. This could come as soon as next week’s Senate Finance Committee consideration of the bill—probably near the end of the process, so as not to draw a lot of attention to it. Once a lot of attention is inevitably drawn to it, they will argue the following: This is just a technical thing, and there’s no way Congress would let the popular individual tax cuts expire as they’ve written them to.

But here’s the messaging problem on that: Republicans, in order to appease their corporate allies who argue that temporary corporate tax cuts wouldn’t provide the “confidence” necessary to spur new investment, would be making the popular individual tax cuts temporary to pay for permanent corporate tax cuts.

How likely are things to play out this way? The tax reform bill that eventually passes, if one does, will have to look very different than the ones that have been released so far to get it in line with Senate rules. The Great Gimmick is nigh.