Want to listen to this article out loud? Hear it on Slate Voice.

The first reports about the horrific attack in Las Vegas on Sunday night will surely evolve into more detailed knowledge. But there are three lessons we might draw from the information already available. First, automatic rifles like the one the shooter apparently used have the potential to kill large numbers of people, particularly when aimed at a crowd in a confined space. Second, a shooter positioned in a high-rise building hundreds of meters away can render moot many of the security measures now used to protect crowds. And third, despite what gun advocates tend to say in response to shootings, it’s incredibly unlikely that any armed bystander could have made a difference, given the distance, elevation, and darkness that separated this shooter from his victims. These three facts made the Las Vegas shooting a nightmare scenario for police agencies, and for the rest of us too.

Based on what we know now, shooter Stephen Paddock was a 64-year-old man who lived a relatively obscure and unremarkable life before his awful final act. He was, according to Las Vegas police, both a “solo actor” and a “lone wolf.” Paddock had no apparent ties to domestic or foreign terrorist organizations, nor had he made his murderous intentions apparent to others before Sunday. Perhaps that helped him acquire his arsenal and plan his attack. Although automatic weapons like those he apparently used are illegal, it would have been perfectly legal for a person like Paddock—a nonfelon who likely didn’t show up on any government watch lists—to acquire semi-automatic weapons and ammunition that could have been almost as deadly.

The first lesson that emerges from Las Vegas concerns the awesome destructive power of modern armaments like the 10 weapons Paddock was reportedly found with. In the hands of even a mediocre shot, an automatic weapon (like the one Paddock apparently shot, based on audio recordings from the scene) can fire 600 or more rounds per minute. The destructive power of such weapons is limited only by their ammunition capacity. In this case, it appears Paddock fired long streams of automatic fire into the crowd, sending scores or hundreds of bullets into concertgoers’ bodies. Bullets from such weapons travel at speeds of 2,000 to 3,000 feet per second, easily covering a third of a mile. On the battlefield, these weapons are used to suppress, wound, or kill enemy troops. In the civilian world, they can quickly kill dozens or hundreds before any effective police response can occur.

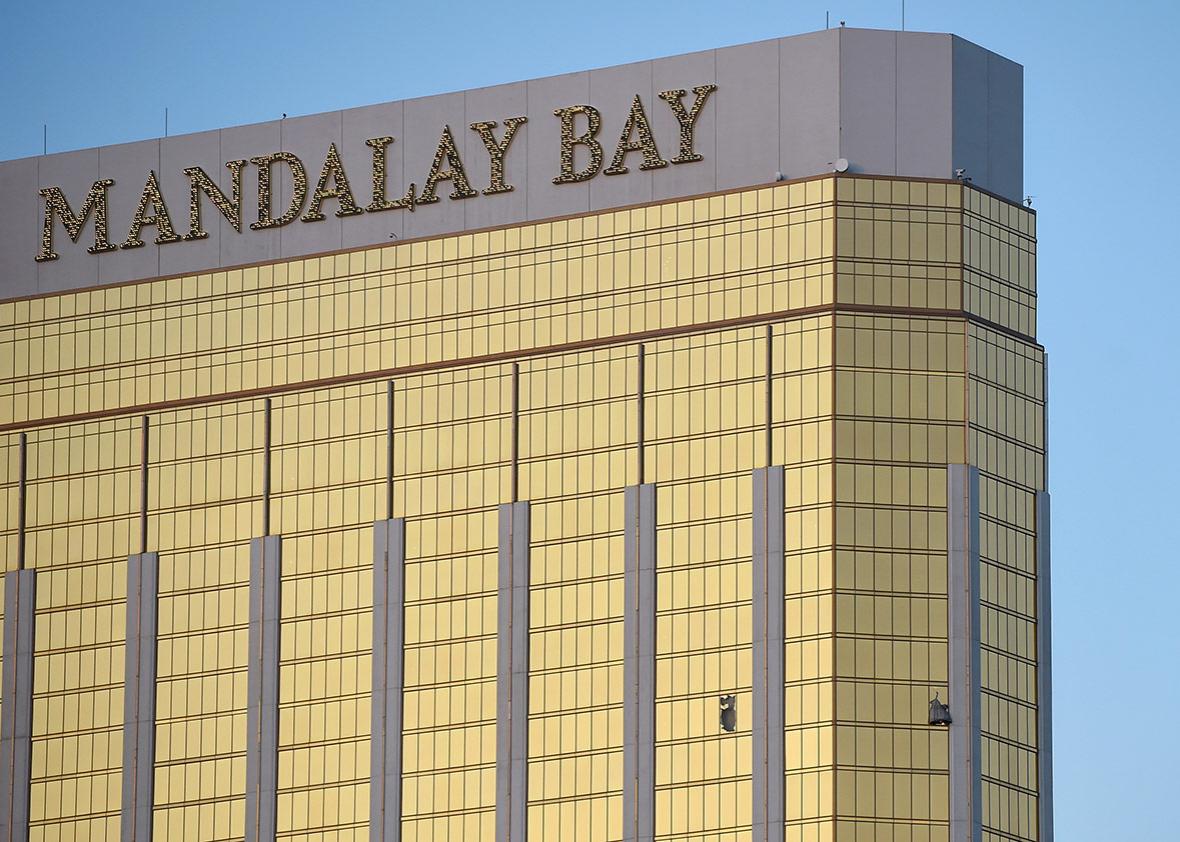

The second lesson from Las Vegas is that the geometry of Paddock’s attack rendered security measures ineffective—even those of Las Vegas, a city with thousands of armed police and security guards on duty around the clock, surveillance cameras covering nearly every inch of ground, and a sophisticated police department with a robust SWAT capability. Paddock apparently fired on concertgoers from a room on the 32nd story of the Mandalay Bay hotel, across the street and approximately 400 meters from the concert. He did so during nighttime, when it would have been difficult to see an open window from the street, let alone someone preparing in the shadows behind it. The distance, elevation, and obscuration make this kind of attack an almost impossible tactical problem for security services. No perimeter security measures or screening checkpoints would help against a threat like Paddock. It would have taken Secret Service–type precautions, of the sort deployed to protect presidents since John F. Kennedy’s assassination, to prevent an attack like this.

A third lesson: It would have been incredibly difficult for any bystander, or even local law enforcement personnel on the ground, to return fire and stop Paddock during his attack. Infantry units are trained to react to snipers by taking cover, obscuring themselves with smoke grenades, and returning fire, often with heavy machine guns, shoulder-fired rockets, or sniper rifles of their own. So are police SWAT teams, although the latter try to use less force and to be more precise in their return fire.

A concertgoer carrying a pistol would have been vastly outranged by Paddock; pistols can barely reach targets 50 meters away. It would have taken a concertgoer carrying a rifle, ideally with a scope and large magazine of ammunition, to respond. And even then, it would have taken the discipline and skill of a Navy SEAL to effectively shoot back at Paddock while under fire, and hit him, while not killing scores more in the Mandalay Bay hotel and turning the scene into a firefight. An armed hotel guest would have fared no better, as it took heavily armed and armored Las Vegas police, guided by the smoke detector in Paddock’s room, to find Paddock in the massive hotel. Contrary to what the NRA may say about shooting violence, a good guy with a gun would have made no difference in Las Vegas.

Attacks like the one that killed 50 concertgoers Sunday night simply should not happen. Our streets should not resemble battlefields; our criminals should not be armed liked soldiers; our police should not have to act like SEAL teams to face down criminals. And yet they do, because the proliferation of sophisticated weaponry makes them impossible to prevent.