The events of the past month have brought into stark relief the truly broken nature of America’s civil-military dialogue. Four U.S. soldiers were killed in Niger, part of an ongoing mission few Americans, including their leaders, were even aware of. The president was criticized for first ignoring, then showing a lack of sensitivity to their deaths. His chief of staff, a former Marine general whose son was killed in combat, criticized the press and politicians for taking advantage of the tragedy for political gain, suggesting that those without a personal connection to the military don’t appreciate the sacrifice of those in uniform and have no standing to comment.

Whatever you think of John Kelly’s remarks, the divide between civilians and the increasingly small number of service members and veterans in the United States is real—and 40 years after the end of mandatory conscription, it’s never been wider. Because of this divide, most Americans have the luxury of ignoring the wars their country is waging on a day-to-day basis around the world, and Congress is under little pressure to rein them in.

Congress has refused to curtail the actions of the president either in this or previous administrations, while showing little interest in grappling with the difficult issues of military engagement. In order to force their hand, there needs to be a requirement to renew an Authorization for Use of Military Force annually—instigating this debate every single year. The renewal should be tied to something so politically unsavory as to ensure Congress does not continue to shirk its constitutional obligations.

In the current U.S. system of government, Congress supposedly retains the power to declare war, therefore acting as a check on the president as commander in chief. The War Powers Resolution, passed in 1973 over Richard Nixon’s veto, codified into law further congressional control over the use of force, however, there is a gray area between war and peace in which many modern presidents have operated.

The broader idea is that while Congress has the power to declare war, the president as commander in chief can use force in either the national interest or self-defense, and then Congress can pass an AUMF or “formal endorsement from Congress of the U.S.’s involvement in military “hostilities” against a particular enemy or set of enemies.” Given the number of military operations the U.S. is currently engaged in, one would think Congress is authorizing the use of force left and right, but in fact there has been no update to the authorizations passed in 2001 and 2002. Sixteen years later, despite changes including the death of Osama Bin Laden and the rise of ISIS, to name just two, the U.S. is still conducting counterterrorism operations under an authorization passed in response to the 9/11 attacks. In practice, congressional oversight simply isn’t occurring.

Secretary James Mattis and Secretary Rex Tillerson both testified in front of the U.S. Senate on Monday to discuss the possibility of a new Authorization for Use of Military Force, yet tellingly, argued the president has all of the authorities he requires under the current one. The media attention surrounding the deaths of four soldiers in Niger appears to have catalyzed momentum for a broader debate of the use of force, but as the news cycle shifts, the debate will likely fade as well. Though testimony by Mattis and Tillerson is a step in the right direction, these arguments have been ongoing for several years, with proposed amendments ultimately voted down time and time again.

So, how do we fix it? Given the nature of the debate, in order to engage the public in the outcome, an annual reauthorization of military should be tied to the revival of conscription. In other words, as a legislative forcing function, the law would require congress to pass a new AUMF every year for every military conflict in which the United States is engaged, or the draft would be reinstated. This would create a feedback loop tying public sentiment to congressional oversight of the use of military force.

To be clear, this is not to argue that reinstating the draft would be good for the country or the military, but rather that the possibility of its reinstatement would give both Congress and everyday Americans a reason to truly think through, every single year, where we’re deploying the military, who we’re fighting, and why.

In 1970, the bipartisan Gates Commission was assembled to examine the U.S. system of conscription and, ultimately, advocated for the end of conscription and the introduction of an all-volunteer military. At the time, the commission grappled with the possibility that this would result in public apathy toward war but dismissed it as unlikely given the toll and sacrifice thought to be required to sustain a conflict. However, with the ever-changing nature of war and increasing reliance on special forces, supposed “surgical strikes” and a very small professional military, national disengagement has not only become incredibly real, but it has far-reaching consequences. Without a new means for reining in the power of the executive by leveraging both congressional and public engagement, the United States risks losing all accountability for how the executive branch wields military might.

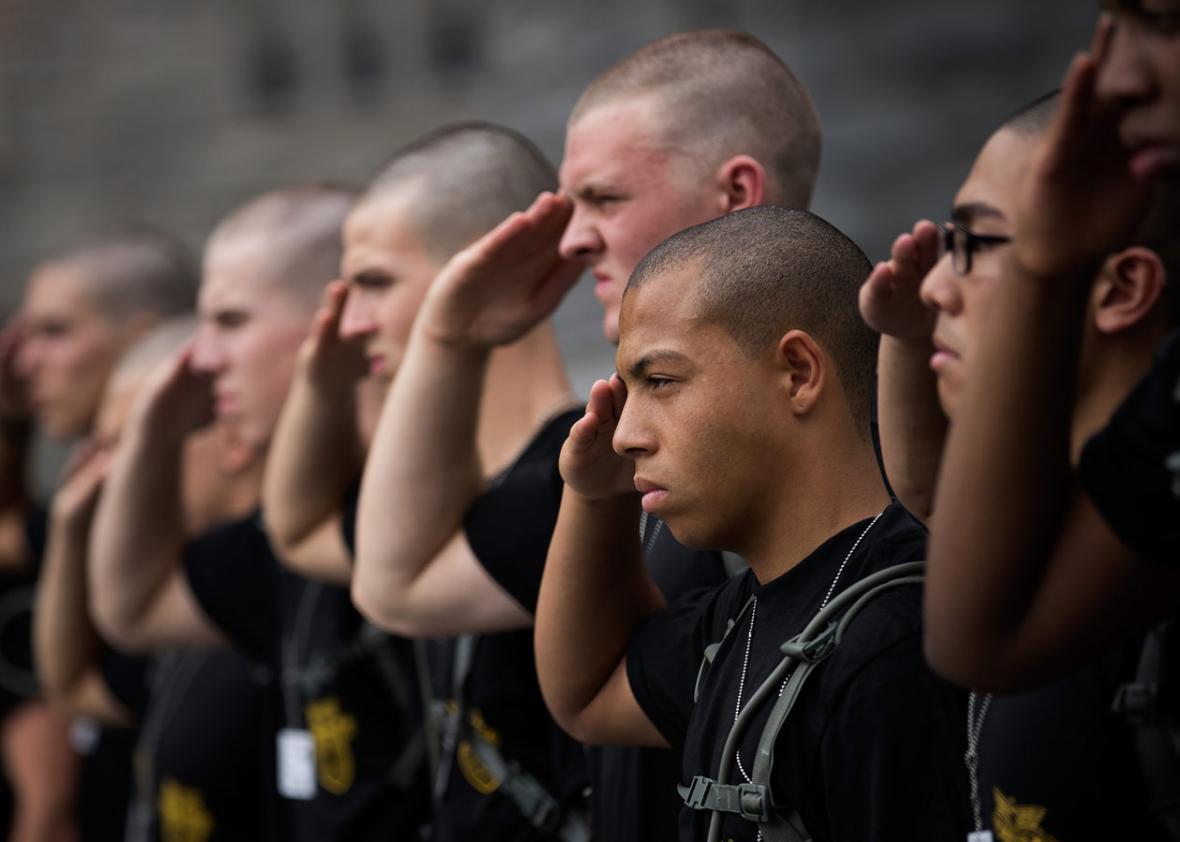

The U.S. military recruits some of the best and the brightest our nation has to offer—smart, physically fit, looking to serve. Yet, even as the military has been largely able to recruit enough volunteers, the lack of conscription has raised the specter of a more fundamental issue. How does a country that is so fundamentally disconnected from its military maintain democratic accountability for the use of force?

Though the military remains the most trusted institution in the U.S. by far, recent surveys show fewer and fewer Americans either know someone or are related to someone in the military, and consequently know very little about military service. The lack of knowledge and overall levels of apathy engender very little congressional accountability with constituents, and Congress in turn has failed to hold the executive accountable. In a “thank you for your service” culture that has left many veterans frustrated and civilians bewildered, the status quo has led to further isolation and a military that is wielded largely by the executive—in both Democratic and Republican administrations alike. In a game of political hot potato, no one wants to be left with the consequences when young Americans come back in flag-draped coffins. It might be easy to blame the public for its lack of engagement, and while it’s certainly concerning, it’s important to consider the other factors at play.

As Gen. Kelly so aptly demonstrated in the Oct. 19 briefing, those who aren’t directly connected to service are often given no voice in these debates, either fearing their lack of credibility and knowledge, or even worse, by having it made clear that the price of admission to comment is military service. With an active duty force of 0.7 percent and a veteran population that hovers just under 7 percent, it’s undemocratic to only give veterans a vote. Not everyone can or should serve in the military, but the next best thing must be engaging and questioning not just those who do, but the civilian and military leadership that issues them life-changing and, at times, life-ending orders. The notion that only those who serve have standing to comment is eroding civil-military relations, but even more fundamentally, it erodes democracy.

The U.S. military isn’t getting any bigger and the country isn’t getting any smaller, so the numbers don’t add up for the type of face-to-face interactions that might normalize military service. Is the proposal for using the draft to force the hand of Congress realistic? Probably not. But neither is continuing down a road in which the military grows increasingly isolated and people continues to adore military service, as long as they don’t have to look at it up close.

The lack of engagement from most of Congress and the public into how and why young men and women are making the ultimate sacrifice on behalf of the country is a clear threat to the democratic accountability that exists from granting Congress the power to declare war. It does a disservice to those who choose to join the military.