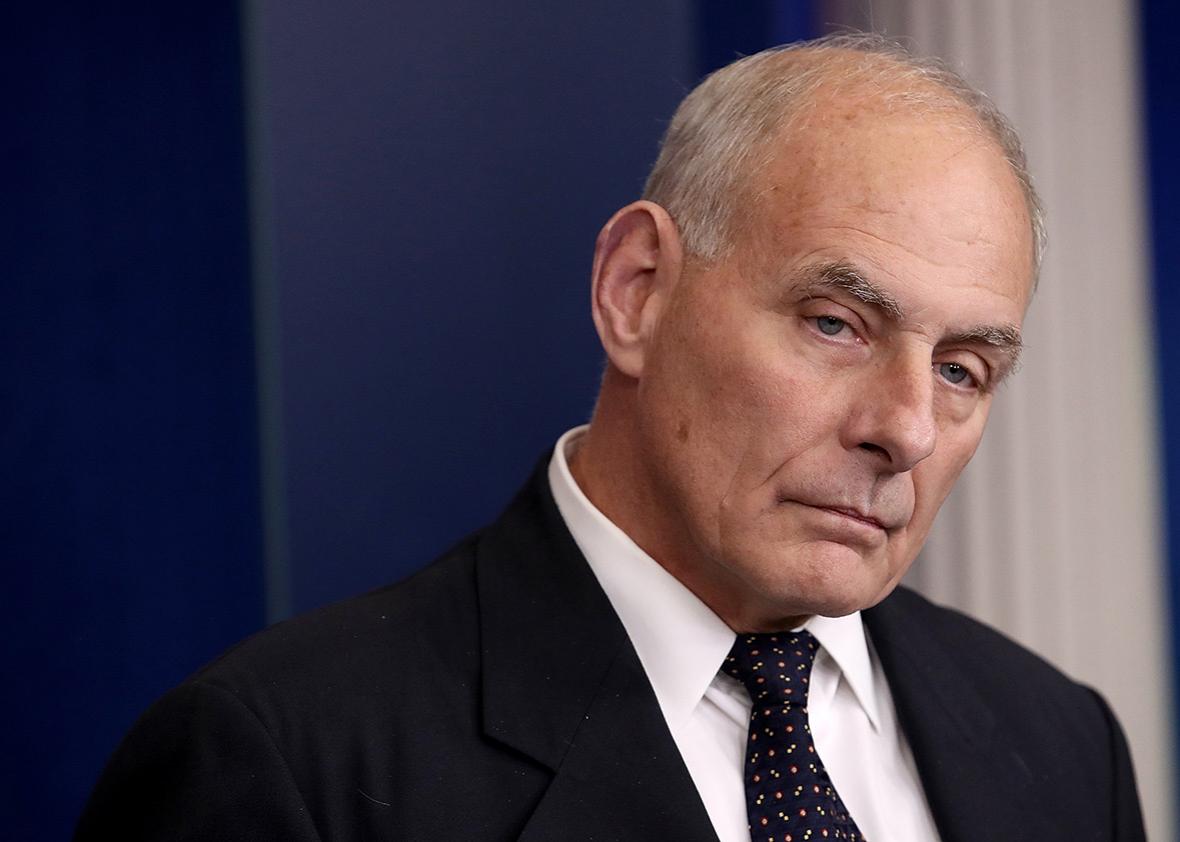

Retired Marine Gen. John Kelly gave a remarkable performance at Thursday’s White House press briefing, deploying his record of service and sacrifice to defend President Trump’s clumsy handling of condolences to the families of four U.S. Army soldiers killed in Niger. Any mistakes by Trump, Kelly said, resulted from advice the erstwhile general had given his boss, with their colloquy including once-private stories about how the Kelly family had received news of their son’s combat death in Afghanistan.

Political aides frequently defend their bosses; some even put their reputations on the line to do so. What made Kelly’s remarks so noteworthy—and powerful, too—was that he mortgaged both his reputation and that of the entire U.S. military to defend Trump. “If you’re not in the family, if you’ve never worn the uniform, if you’ve never been in combat, you can’t even imagine how to make that call,” said Kelly, defending Trump’s remarks to the widow of Army Sgt. La David T. Johnson and suggesting it might be unpatriotic to question the actions of the military or its commander in chief. Indeed, White House press secretary Sarah Sanders followed Kelly’s lead on Friday, asserting that any critique of Kelly was inappropriate because of his stature as a retired Marine general.

These comments are best understood against the backdrop of America’s civil-military divide. Since the end of conscription at the end of the Vietnam War, this divide has deepened and widened. Today, just 0.7 percent of Americans are on active duty or in the reserves; roughly 6.6 percent of Americans have served at some point in their lives. War, as my colleague Amy Schafer has written, has become a family business, with vastly higher rates of service among military families like the Kellys. By the Pentagon’s last count, 2,978,246 service members had deployed to Iraq, Afghanistan, or other theaters of war since Sept. 11, 2001; 1,454,026 of these service members have deployed more than once, with an average of 2.04 deployments per service member. These are, in Kelly’s words, “the best 1 percent this country produces.” The burden of our post-9/11 wars has been heavy but not widely shouldered nor shared. The result, echoed in opinion surveys of veterans and military personnel, has been a mixture of pride, nostalgia, and resentment.

Kelly’s comments reflected this complex combination of feelings, as well as his station within the military tribe as a retired four-star Marine general who joined the military immediately after Vietnam. There was also a great tension in Kelly’s remarks, between his apparent craving for understanding of his service and sacrifice and his rejection of any possibility that the public could ever understand.

Early in his remarks, Kelly described in exquisite detail the process by which the U.S. military returns its fallen home, from last rites and “ramp ceremonies” near the battlefield to painful notifications by casualty assistance officers to a final interment with full military honors. It sounded as if he was desperate for his nation to understand the love and devotion between and among members of the military, and the purpose to which they devote (and sometimes give) their lives.

And yet he closed with a lament: “We don’t look down upon those of you who that haven’t served. In fact, in a way we’re a little bit sorry because you’ll have never have experienced the wonderful joy you get in your heart when you do the kinds of things our servicemen and women do.” He’s right, to a point, in suggesting that those who do not serve cannot truly understand the love—and pain—experienced by those in uniform and their families. At the same time, he undercuts his message by suggesting a finite limit to the compassion that he and the military might expect from society.

No consensus exists among veterans as to how to reconcile or even address this tension between understanding and separation. Many leading veterans organizations—especially those founded since 9/11—see it as part of their mission to bridge the civil-military divide, recognizing that the divide can have adverse consequences for veterans’ transition and integration after service. But veterans also celebrate their differences from society in ways small and large. Drill sergeants inculcate these differences into recruits during boot camp, teaching them they are better and tougher than civilians. Service members wear the “1 percent” moniker invoked by Kelly as a badge of honor. Social media memes abound comparing today’s military to ancient Sparta and lamenting the relative softness of American society. This resentment and superiority comes through clearly in polling of post-9/11 veterans, who feel they went to war while everyone else in America went on with their lives.

It’s striking that Kelly feels comfortable highlighting the civil-military divide, and even emphasizing its virtues, from the lectern of the White House briefing room. Kelly’s remarks break with the popular view among many of his contemporaries that the divide is a bad thing and that the military has grown too far apart from the nation during the 44 years of the all-volunteer force. Indeed, Defense Secretary James Mattis (Kelly’s former comrade from the Marine Corps) edited a book on the topic last year before joining the Trump administration. But perhaps Kelly’s views should not be surprising given his pedigree as a retired Marine (the Marines have always stood apart from the other services with respect to their martial virtues) and his own record of service and family sacrifice. Kelly reflects a slice of military sentiment that exists in barracks and team rooms across the globe but rarely appears in public.

Nonetheless, the implications of Kelly’s performance should worry us. If there’s no role for civilians to play other than to salute the military and give them resources, that would seem to invert the relationship between the military and the nation it’s supposed to serve. If civilians cannot fully appreciate the military, they may too easily resent service members or veterans when they disagree with military policy. And if Americans—even those who have not served—cannot understand the military, then our battles will increasingly be fought by a warrior caste of families who can look only to each other for support.

We should worry, too, about a president who hides so often behind bright medals and pressed uniforms. Kelly may have gone out on stage of his own volition, but the Trump administration has been all too willing to leverage his gravitas to score political points, just as it has deployed Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster and before him retired Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn to wage its political fights. Doing so may help Trump escape his current political scrape, but he’ll do so at the cost of the long-term reputation of the military, and its proper role in society.