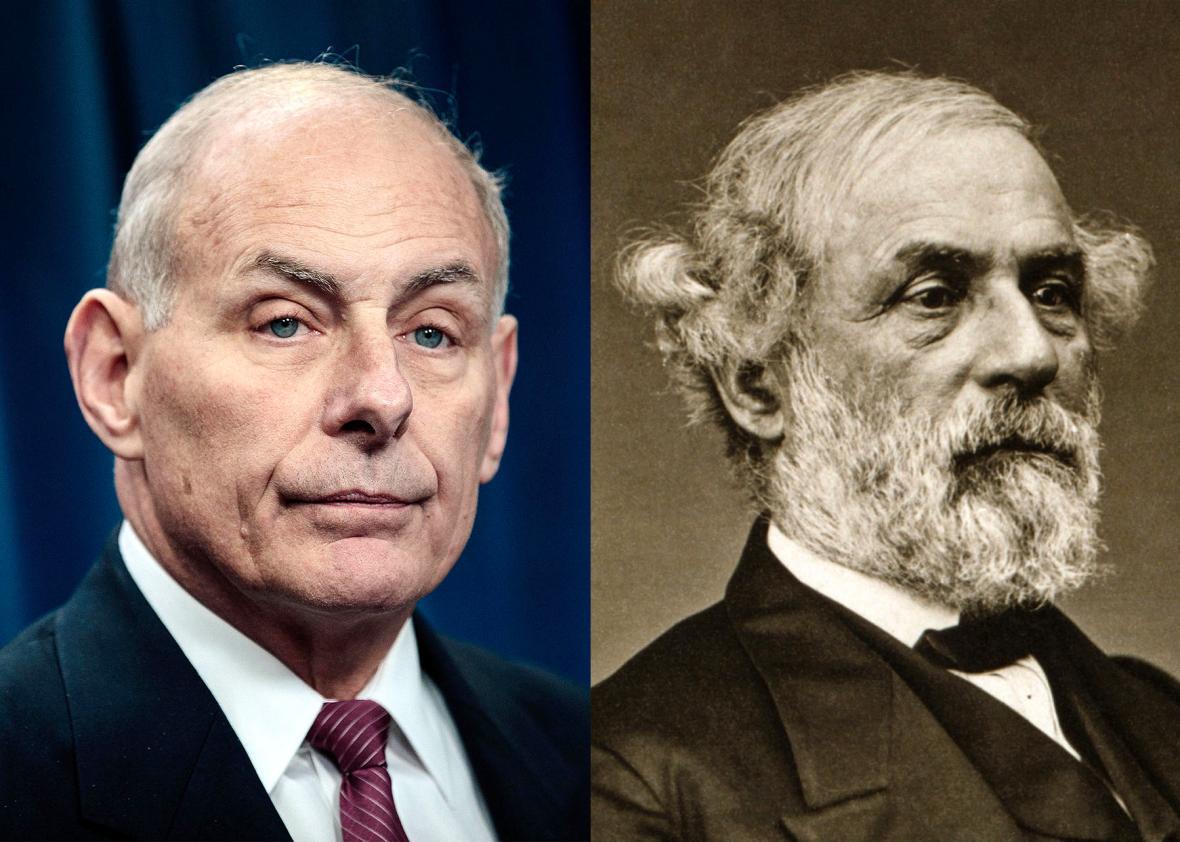

On Monday night, Chief of Staff John Kelly offered what may be the official White House position on historiography.

“I think we make a mistake as a society … when we take what is today accepted as right and wrong and go back 100, 200, or 300 years or more and say what Christopher Columbus did was wrong,” Kelly told Laura Ingraham in an interview on Fox News. “Five hundred years later … it’s inconceivable to me that you would take what we know now and apply it then. It shows you a lack of appreciation for history and what history is.”

It shows a lack of appreciation for history and what history is.

It is true that one of the tasks of history is to understand the past on its own terms, to see the world of our predecessors with their eyes, and to grapple with them as moral agents, with the same capacities—with the same humanity—as ourselves. W.E.B. DuBois captured this in his prologue to Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880, when he informed readers that he intended to tell the story of the post–Civil War years “as though Negroes were ordinary human beings”—a challenge to his white contemporaries who often treated them as historical objects for theories of race hierarchy, not humans acting and reacting as humans do.

Kelly clearly believed he was meeting that standard later in the interview, when he offered praise for Robert E. Lee:

I’ll tell you, Robert E. Lee was an honorable man. He was a man who gave up his country to fight for his state, which 150 years ago was more important than country. It was always loyalty to state first back in those days. Now it’s different today. The lack of an ability to compromise led to the Civil War, and men and women of good faith on both sides made their stand, where their conscience had them make their stand.

Most of the backlash to Kelly’s comments centered on that last claim, that the Civil War was a failure to compromise. Writers like Ta-Nehisi Coates of the Atlantic and historians like Adam Rothman of Georgetown University blasted that view, showing how it was compromise that defined the antebellum era—from the Missouri Compromise of 1820 to the Compromise of 1850 to the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854—and how those compromises simply deferred the issue of whether the United States would remain “half free and half slave,” to borrow Abraham Lincoln’s words.

It’s not that Americans could no longer compromise. In the midst of the secession crisis, Sen. John Crittenden presented a compromise that would preserve slavery, and Lincoln himself entered office offering a fig leaf to the slave South, carrying it until the war made emancipation the only option. It’s that ultimately there was no compromise to make with human bondage and all of its attendant crimes.

In searching for the cause of the Civil War, the answer is the same as it always was. Most Americans at the time—North and South, free and slave—understood the war was centered around slavery. Confederate leaders proclaimed it in their calls for secession, individual soldiers explained it to their families and loved ones, and enslaved people grasped it as the conflict unfolded and they forced the Union to confront the question of their bondage.

The notion that Lee’s “honor” has a role in this question, or that the war was caused by passions on both sides, is an artifact of the “Lost Cause,” an influential (and largely successful) movement to reunify the white North and the white South around a narrative of sacrifice and bravery, one that valorized Lee, downplayed slavery, and removed black Americans entirely, except as naifs and villains in the subsequent story of Reconstruction.

In defending Lee, Kelly shows he’s captive to that myth. He seems to want to preserve a heroic image of Columbus and Lee—and of the American past at large—and to do that, he’s flattened its landscape, sanded its edges, and cleared it of dissenting voices.

Lee wasn’t the only Southerner—or the only Virginian—forced to choose between “his state” and “his country.” Facing war, George Henry Thomas, one of Lee’s subordinates, had to make the same choice. He chose Union. As did David Farragut, a native of Tennessee. As did Winfield Scott, another Virginian. The United States of 1860 was a different place, and Americans understood their relationship to the country in different ways. But in showing us other men in similar straits who took the opposite path, history doesn’t exonerate Lee; it condemns him.

The same is true of Christopher Columbus. To defend him on charges of present-ism is to ignore figures like Bartolomé de las Casas, who opposed the subjugation and enslavement of indigenous Americans around the same time. It’s to ignore how Columbus was briefly punished by the Spanish crown for his brutal treatment of natives. In short, it’s to betray one’s own ignorance of this period of Western history.

Kelly’s historical relativism only works if one centers the beliefs and experiences of Europeans and, in the case of 19th-century Americans, white people. Ignore Columbus’ peers and you’re still left with the fact that Native Americans were surely critical of his atrocities. Do the same for Lee and there’s no question that black people—some 4 million of them—opposed their enslavement. You can only claim it was the time, and people had different values if the people in question aren’t the victims. To take that view is to adopt the morality of the powerful, whether conquerors or colonizers, slaveholders or their sympathizers.

Kelly’s comments aren’t just bad history—they matter for our politics too. His echo of neo-Confederate talking points comes as the Republican candidate for governor of Virginia traffics in neo-Confederate imagery, and just a few months after President Trump defended a violent group of white nationalists who gathered in Charlottesville, Virginia, to protest the removal of a monument to Lee. In the meantime, Trump attacked black NFL players, a black sports commentator, and a black member of Congress, whom Kelly himself vilified from the White House briefing room with a false story of her alleged selfishness, after she criticized the president for disrespecting a black service member and his widow.

To judge Trump and his White House by their substantive accomplishments, it has been a failed year on every front. But judge them as culture warriors—as racial demagogues, quick to inflame or pander to white racism—and they’ve done considerable damage.