After a 64-year-old white man from Nevada killed at least 59 people and injured more than 500 at the Route 91 Harvest Festival in Las Vegas on Sunday, grief-stricken calls for better gun control and more comprehensive health care (both psychiatric and physical) flew around the media. Voices from the right shot those calls down, playing their predictable role in the script of American gun violence. There is an inevitable push from pro-gun stakeholders not to “politicize” the tragedy of shooting deaths. President Trump obeyed that command when he posed behind the Oval Office lectern and spurted meaningless clichés about “standing united” against “pure evil.” “Not a scintilla of politics,” tweeted Howard Kurtz in praise of our foremost politician’s response to one of the bloodiest mass shootings in American history. “Gun control is a legitimate issue, but for the Dems already raising it after Las Vegas massacre, could we just have a day before plunging in?”

Kurtz’s request that we avert our eyes from the facts that led to an unthinkable (yet preventable) loss of life sounds at once illogical and morally repugnant. While large swaths of society prefer to veil the horror of Las Vegas in “thoughts and prayers,” many more people are trying to instigate conversations about our pro-gun culture and white male resentment and emergency preparedness training. What would the world feel like if we all just kept our mouths shut instead? Coverage of the 1949 killing spree that is widely considered a precedent for today’s all-too-frequent massacres provides some clues.

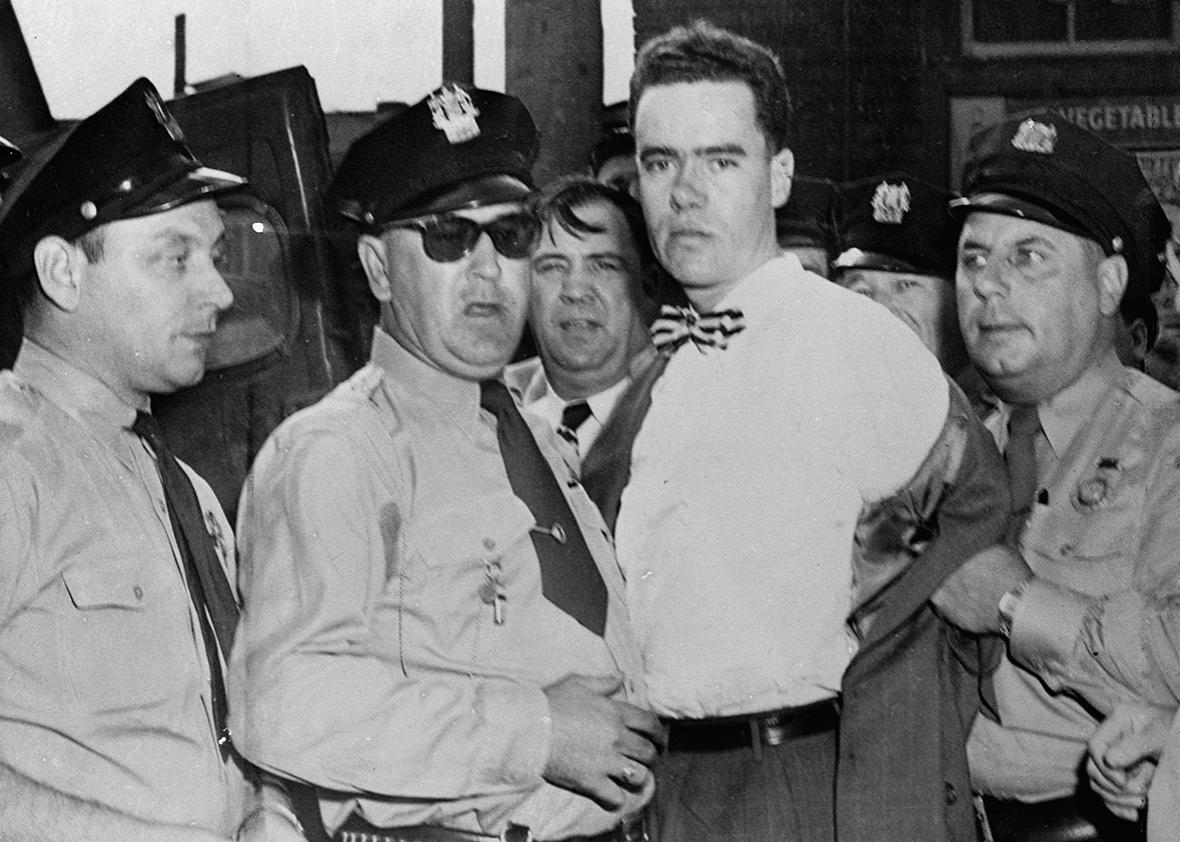

Howard Unruh’s 1949 “Walk of Death” through Camden, New Jersey, left 13 dead and three injured. Contemporaneous accounts of his “berserk” rampage—most notable among them the extensively syndicated, Pulitzer Prize–winning account from the New York Times’ Meyer Berger—are colorful, cinematic, and intensely visual. These pieces were designed less to soberly inform than to titillate and transport. In his detailed breakdown of how the “Walk of Death” unfolded—the circuit involved Unruh’s mother’s house, a cobbler, a tailor, a barber, a neighborhood restaurant, a druggist, and a stranger’s apartment—Berger offers up narrative minutiae he can’t possibly know. “He [Unruh] took one last look around his bedroom before he left the house,” we read. This vivid voiceover doubles as a transition into the ghastly décor Unruh presumably sees: “Scattered about the chamber were machetes, a Roy Rogers pistol, ashtrays made of German Shells, clips of 30-30 cartridges for rifle use and a host of varied war souvenirs.”

To weave a rich and absorbing tale, Berger borrows cliffhanger techniques from suspense novels. “Mrs. Smith [a victim] could not understand what was about to happen,” he writes. A different, doomed townsperson turns “from his work to see the six-footer, gaunt and tense, but silent, standing in the doorway with the Luger. Unruh’s brown tropical worsted suit was barred with morning shadow. The sun lay bright in his crew cut brown hair.” It is as if a stanza of imagist poetry by Ezra Pound married a Hitchcock still and birthed a news account.

Scattered throughout the piece are superficial strokes of characterization. Unruh is a skilled sharpshooter who served in the U.S. Army. He is deeply religious (fixated on scriptural prophecies). Most acquaintances call him “soft-spoken,” “close-mouthed,” and “polite.” But Berger’s account remains incurious about his motives, the context that produced him and his rage, and the policies that enabled him. The Times was far from alone in pursuing a shallow approach. Charley Humes, a journalist for the Camden, New Jersey Courier-Post, opened his Sept. 7, 1949 piece in medias res, with a sensational appeal to readers’ tender feelings: “ ‘Kids … little kids … murdered in their own home.’ Tears were streaming down the face of a lovely little lady as she spoke these words.” Sentimentality substitutes for examination. Descriptions of the carpet—“in front of her … was a spot, sort of whitish, where someone had tried to remove the blood of a little boy … a little boy who never harmed no one”—chase the kind of catharsis that signals closure, the end of the play. Instead of energizing us to seek reform, this writing wants to paralyze us with empathy.

Dispatches from the Philadelphia Inquirer were similarly lurid and ironic, reveling in the contrast between the “pious, mild young man” and his brutal deeds. One reporter speculated pruriently about his romantic life, noting that he made “little time for girls.” While the Associated Press reported that Unruh’s brother “blamed the slaying on his service in the army,” the killer’s military career was treated as another piquant detail, similar to the revelation that he built his own model trains. Unruh was cast as a one-off, a peculiar and garish figure to gawk at, not a problem to solve or a phenomenon to unpack.

“The shock was great,” Berger concludes at the end of his 4,000-word epic, sealing it with a motto and thesis statement. “Men and women kept saying: ‘We can’t understand it. Just don’t get it.’ ”

These reporters and essayists inhabited a world in which mass murder via firearm was vanishingly rare, not one beat in a recurring macabre rhythm. They had no way of foreseeing that nearly 70 years later, gun violence would so engulf the United States that our response to the slaughter of 59 or more people would feel rote and rehearsed. Unruh’s chroniclers didn’t need to search for structural explanations—irrational gun laws; toxic white masculinity—to make sense of thousands of lost lives. The only thing to “get” when it came to telling Unruh’s story was the story of the man himself.

When the NRA and right-wing pundits entreat us to “not politicize” gun deaths, they are asking us to follow Berger’s example, which means leaving the reality we’re inhabiting in 2017 and traveling back to 1949. They wish to lay responsibility for all these fatalities at the feet of no one aside from a handful of anomalous wackadoos. But as a country, our grace period is over: We’ve run out of excuses for framing gun violence as apolitical and inexplicable. We cannot talk about shootings as though we have not lived through them before, or as though we aren’t certain to live through them again. To politicize the gun murders of 2017 is to acknowledge that we are steeped in a knowable set of causes that deliver predictable outcomes. To not politicize them is to play pretend, or to lie.