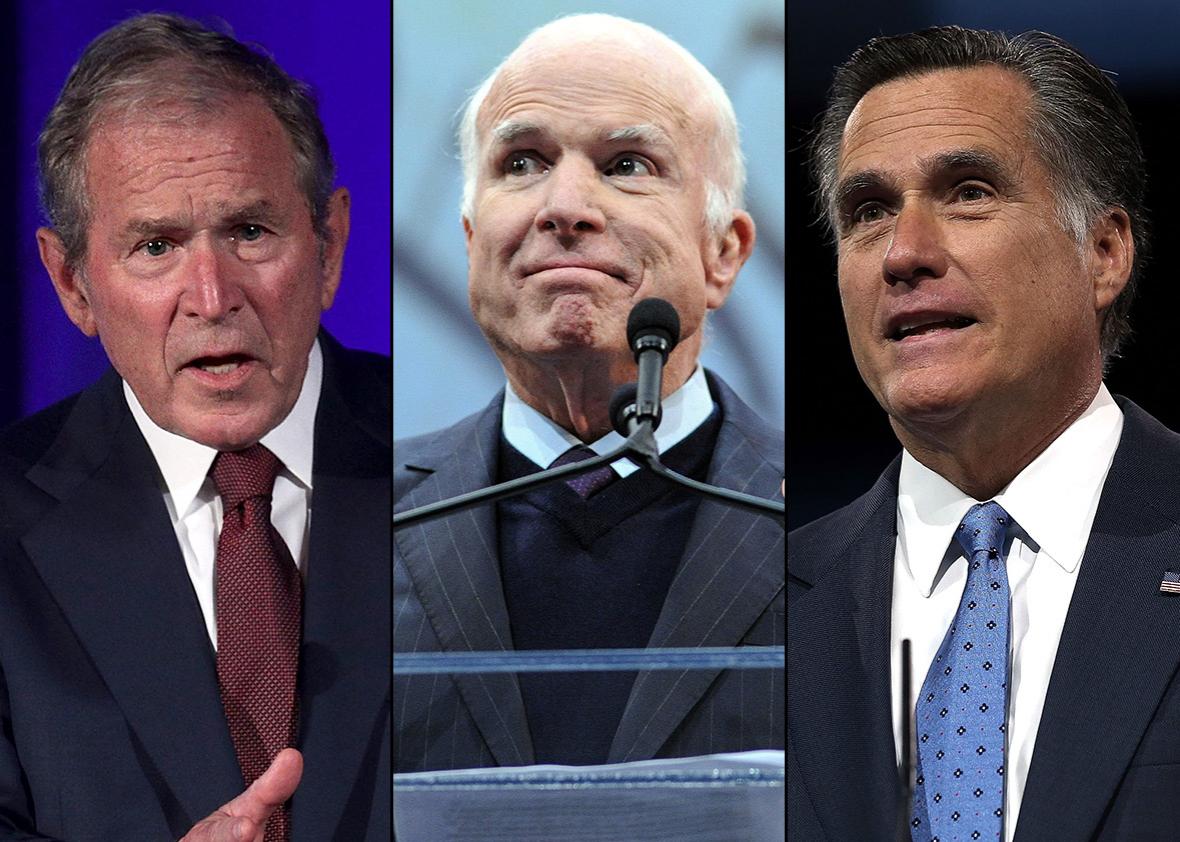

On Monday, Sen. John McCain denounced President Trump’s philosophy, agenda, and conduct. On Thursday, former President George W. Bush did the same thing. Neither mentioned Trump by name, but their target was clear. They echoed former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney, who spoke out against Trump last year. These three indictments, issued by the men who represented the GOP in the four elections leading up to Trump’s, are more than ghosts of a dead party. They point toward an alternative vision of conservatism.

You don’t have to love Bush, McCain, or Romney to heed their words. You don’t even have to be Republican. Maybe you think that the Iraq war was worse than anything Trump has done, or that McCain is a blowhard, or that Romney is a hypocrite for sucking up after Trump was elected. But there’s going to be a conservative party in this country, and some kinds of conservatism are better than others. At its best, conservatism stands for morality and freedom. Trump stands for neither. We’ll be a better country if our conservative party listens to Bush, McCain, and Romney, not to Trump.

Trump speaks of Americans as a people who share a language, guard a border, and bleed the same blood. The white supremacists who marched in Charlottesville, Virginia, two months ago parroted him—and the Third Reich—by chanting “blood and soil.” McCain sees us differently. “We live in a land made of ideals, not blood and soil,” the senator argued.

Without mentioning anyone by name, McCain called the empty nationalism of Trump and Steve Bannon “spurious” and “unpatriotic.” The United States “wouldn’t deserve” to “thrive in a world where our leadership and ideals are absent,” he said. Victory for our country, at the expense of its values, would be worthless.

Bush, too, spoke of “the DNA of American idealism”:

Our identity as a nation—unlike many other nations—is not determined by geography or ethnicity, by soil or blood. … We become the heirs of Thomas Jefferson by accepting the ideal of human dignity found in the Declaration of Independence. We become the heirs of James Madison by understanding the genius and values of the U.S. Constitution. We become the heirs of Martin Luther King Jr. by recognizing one another not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.

That recognition is what distinguishes American patriotism from the patriotism of other countries. Here, national identity and national values are supposed to be synonymous.

In international affairs, this means that America must stand for human rights. Freedom is “the defining commitment of our country,” said Bush. We must speak “for dissidents, human rights defenders, and the oppressed.” McCain, too, spoke of liberating people from tyranny through “the international order we helped build.” You can argue that Bush and McCain pursued this objective rashly in Iraq. But Trump doesn’t make that argument. He dismisses human rights as a priority altogether. Our big mistake in Iraq, Trump has often said, is that we didn’t seize its oil.

The fundamental difference between Trump and the previous three GOP nominees isn’t that they misjudged Iraq. It’s that they believe in moral constraints, and he does not. “We don’t covet other people’s land and wealth,” McCain said four months ago, alluding to Trump’s lust for Iraqi oil. In his speech last year, Romney said of Trump: “He calls for the use of torture. He calls for killing the innocent children and family members of terrorists.” That’s one reason why Bush, McCain, and Romney recoil from Trump’s embrace of Vladimir Putin. Russia and China are trying to undermine “the norms and rules of the global order,” Bush pointed out. Trump would help them do so.

When you define America by its ideals, they affect how you think about immigration. Trump thinks his job is to protect the people already here. That’s a normal assumption, if you live in an ordinary country. But America isn’t ordinary. It’s “the land of the immigrant’s dream,” said McCain. Bush lamented that his countrymen, possessed by “nationalism distorted into nativism,” have “forgotten the dynamism that immigration has always brought to America.” Even Romney, who once spoke of self-deportation, protested that Trump “scapegoats” Mexican immigrants.

The debate between blood, soil, and ideals doesn’t end with immigration. It colors how we view citizens who are already here. Understanding America as an idea “means that people of every race, religion, and ethnicity can be fully and equally American,” said Bush. “It means that bigotry or white supremacy in any form is blasphemy against the American creed.” To Romney, this is personal. While Mormons see themselves as Christian, they know what it’s like to be treated as a religious minority. Three times in his speech, Romney condemned Trump for slandering and vilifying Muslims.

To Trump, the idea of an American creed is foreign. He sees Americans as a team competing against “the Chinese,” “the Persians,” and other rivals. In speeches, he reads scripted words about how we’re all one people, regardless of color. But in unscripted moments, he has no compunction about casting suspicion on Muslims, Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, and Seventh-day Adventists. He identifies with the “very fine people” who rally on behalf of Confederate statues, even when the rally ends in racist violence.

In the absence of ideals, conservatism simply defends old arrangements. It shields prejudice and injustice. That’s the peril of Trump’s pledge to “make America great again.” After the crisis in Charlottesville, he defended Confederate monuments by invoking “culture” and “heritage.” But heritage can mean more than slavery, states’ rights, or cotton. The Constitution is part of our heritage. So are the words of the Declaration of Independence, even if they were dishonored for another century. What makes America great is its struggle to be greater, and the job of a principled conservative party is to explain how our inherited values can guide us. In his speech, McCain praised the United States not just for winning World War II, but for what it has done since: “We made our own civilization more just, freer, more accomplished and prosperous than the America that existed when I watched my father go off to war on Dec. 7, 1941.”

A country of ideals is stronger than a country of blood and soil. Because it’s less prone to internal strife over religion or ethnicity, it’s better able to defend itself. In that spirit, Bush challenged Trump to stop downplaying Russia’s efforts “to feed and exploit our country’s divisions.” But the greater threat lies within. A country built on values can lose them. Trump “cheers assaults on protesters,” Romney warned in his address last year. “He applauds the prospect of twisting the Constitution to limit First Amendment freedom of the press.” The danger of Trump, and a ruling party that follows his path, isn’t that America will lose to China. It’s that we’ll win, but we’ll no longer be America.