Tom Price has now returned to Georgia, presumably flying commercial. Scott Pruitt is under investigation by the EPA’s inspector general for frequent private jet travel to his home state of Oklahoma. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, a billionaire, tried to book a military jet to fly himself and his wife, Louise Linton, to Europe for their honeymoon. And there’s Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, who appears to be asking that taxpayers subsidize travel that combines the glorious trifecta of work, exclusive fundraisers, and ski trips.

In a Trump administration rife with double-dealing—the president himself owns a pay-to-play hotel just down the street from the White House, where diplomats and lobbyists know they must be seen—his Cabinet secretaries’ penchant for private jets has struck a special nerve. And it’s not just the profiteering—the way the president cashes in each time he drags the Secret Service to a Trump property for another golfing vacation. It also aggravates that sore place that airports and air travel, as measuring sticks of economic anxiety, have come to occupy in American life. Private jets are out of reach for even wealthy Americans. Federally regulated airports and big airlines are widely loathed by the rest of us. Skirting the latter in favor of a cushy jaunt on the former has struck even members of the executive branch as a gesture of intolerable superiority.

All this is best captured in a memo released when Price resigned at the end of September, at which point budget secretary Mick Mulvaney dutifully reminded his colleagues of the undemocratic implications of private jet travel. “With few exceptions,” he wrote, “the commercial air system used by millions of Americans every day is appropriate, even for very senior officials.” That was what Trump thought, too. Price—whose history of self-dealing was well-known at the time of his confirmation—was a “fine man.” But even for this president, the private jet reports were “not good optics.”

This is an ironic twist for a president who sold his alleged business acumen to Americans in front of a Boeing 757, which served as a gargantuan prop at his campaign tarmac rallies. Trump Force One, as his fans call it, is not a typical private jet. It’s a repurposed commercial airliner that would have ferried more than 200 passengers in its prior life as a Danish and then Mexican passenger plane. It’s less a luxury transportation vessel than a flying apartment.

Trump is obsessed with air travel. He even briefly got into the airline business himself, purchasing Eastern Air Shuttle and its rundown fleet of 727s in 1988. As Barbara Peterson recounted in the Daily Beast in 2015, he made terrible business decisions, like trying to add ceramic sinks to the bathrooms and brass handles to the exit doors, heavy additions in a business where shedding weight is paramount. (He did try to shed weight via an unwise attempt to cut the cockpit crew from three pilots to two). But he wanted the planes, and their attendants, to have “the look of old money.”

Regardless of his bad business acumen and poor taste, Trump had been so accustomed to pancake layers of luxury that the prestige of the presidency left him visibly disappointed. The longtime Maryland presidential retreat Camp David, he told a European journalist, “is very rustic, it’s nice, you’d like it. You know how long you’d like it? For about 30 minutes.” More recently, he allegedly called the White House a “dump.”

He is quite literally banking on his own presidency—renting rooms to foreign diplomats and domestic lobbyists, doing disaster recovery while wearing a USA hat he then sells online, injecting his own corporate priorities into American diplomacy, and refusing to disclose how much money he would save under his tax plan. But it’s telling that the crassness of his own millionaire Cabinet—lunging for private jet travel with the unseemly eagerness of hungry guests scarfing down the canapés—is the scandal that seems to have caught on with the public and brought real consequences. Price spent more than a million taxpayer dollars on private air travel while health care foundered in Congress. Even Mnuchin—whose personal fortune should have made him less sensitive to the temptation—is alleged to have booked a private jet trip to Fort Knox just for the frisson one gets from watching a solar eclipse from atop a mountain of gold. Trump was famous for being rich before he became president; flying around on private planes is part of his shtick. Members of his Cabinet, by contrast, seem like gauche arrivistes, riding their boss’s coattails at great taxpayer expense.

Catherine Rampell reports that this problem is not a new one. It was also prevalent in the Roman Empire, where politicians and soldiers routinely abused their travel privileges, stoking the resentment of provincial villagers and earning rebuke from their supervisors. She quotes one such edict from an imperial governor of Egypt circa 133-137 A.D.:

I have learned that many soldiers, traveling through the countryside without a diploma, unjustly demand boats, baggage animals, and men, sometimes taking things by force, sometimes receiving them from the local governors as a favor or service. As a result, private citizens suffer insults and abuse, and the army is accused of greed and injustice. Therefore I command once and for all that the local governors and their lieutenants furnish none of the things given for escort to anyone without a diploma, neither to those going by boat nor those traveling on foot. I shall forcibly punish anyone who, after this proclamation, is caught either taking or giving any of the things specified.

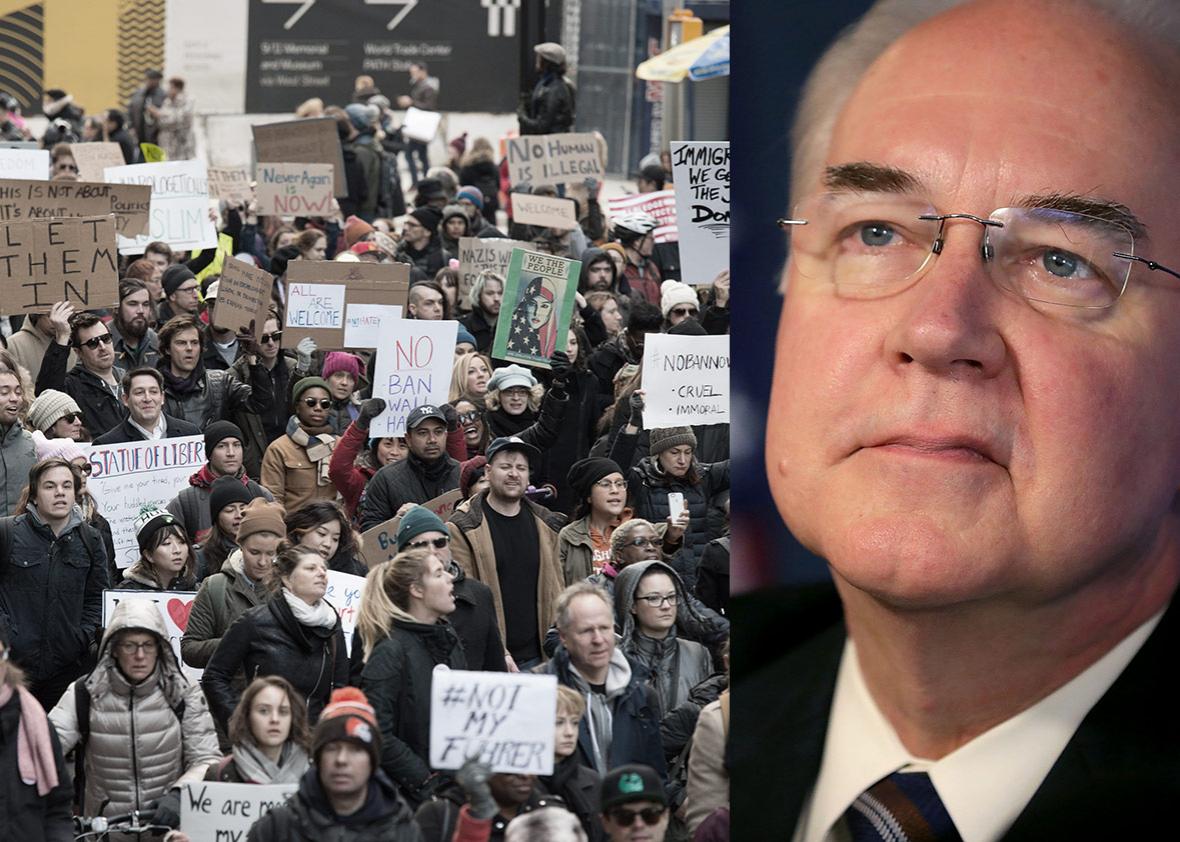

These recent travel scandals serve as a kind of privileged rejoinder to the one great spontaneous and sustained street protest of the Trump administration, what in some quarters has been called the Airport Revolution. At the end of his first week in office, the president rolled out a constitutionally infirm and openly bigoted travel ban, one so poorly drafted that his own acting attorney general refused to enforce it. (Sally Yates was subsequently fired for her impudence.) As border patrol officers clumsily tried to enforce Trump’s edict to turn away lawfully admissible travelers at airports around the country, thousands of Americans started showing up at airports around the country, blocking arrivals terminals and flooding streets and baggage claim areas. Nobody was more surprised than Trump, who insisted that the rollout was going “nicely” even as protesters, lawyers, and elected officials swarmed the nation’s airports to sing the national anthem, offer aid to stranded travelers, and demand that lawful visa holders be released from detention.

By that evening, a court had ruled against the travel ban, which not only singled out Muslim-majority countries but also favored Christian refugees seeking to enter the U.S. Since then Trump has attempted the same move twice more, lightly rinsing his directive for racism. Never again, though, has there been an attempt to turn away travelers en masse at airports. That’s in no small part because Americans came together to demonstrate that we are not a country—at least, we haven’t been and shouldn’t be a country—that allows such a thing to happen. The anti-Trump resistance has been searching for a second coming of the Airport Revolution ever since.

There is a poetic symmetry between these two scandals—the rich escaping the airport, refugees trapped inside—that makes them look like two sides of the same coin. Consider too that airports are the place where Trump’s draconian security measures—from proposed laptop bans to invasive facial recognition technologies to proposals for privatizing airport security and unprecedented sweeps seeking out illegal immigrants—seem to run aground. Perhaps this is the reason Americans who’ve grown steeled to the routine kleptocracy of Trump’s America can even now evince shock at a Cabinet secretary taking a private jet: Despite its indignities and iniquities, commercial air travel remains the great leveler, making harried travelers of us all. It’s at once a privilege we still afford those seeking sanctuary and a punishment we like to see meted out to the aristocracy.