Congress returns from its summer vacation this week with a long list of straightforward legislative tasks it needs to complete to keep the country’s trains running on time.

You should be terrified.

In addition to reauthorizing various federal agencies and programs, Congress’ most pressing tasks will be funding the government and raising the debt ceiling by the end of the month. If the former doesn’t happen, we’ll face the first government shutdown since 2013; if the latter doesn’t happen, the creditworthiness of the United States will go to the dump, and with it, the economy.

At the moment, Hurricane Harvey seems to have taken some of the fire out of certain actors’ desire for brinksmanship. And the need to pass a disaster relief package has provided congressional leaders with some potent tactical options for moving the rest of the agenda through with it. The only thing that could change this sudden détente is … the brief passage of time, when our nation’s fine legislators and president forget about Harvey and decide they want to fight each other to the death again.

These are some of the key variables that will determine whether Congress can get through the month smoothly, or at least smoothly for Congress.

Will President Trump agree to delay his fight for border wall money?

Our main man is sick and tired of the delays and wants his wall, and he needs the American taxpayer to pony up for it.

Two weeks ago at his Phoenix rally, Trump said that he would be willing to shut down the government if Congress did not appropriate wall money in the September funding fight. Harvey, though, may have given him an out from that threat: He can secure disaster funding from Congress and take that as his “win” for the month instead. This is what Congress, and members of his administration, seems to be urging him to do. Even the far-right House Freedom Caucus recognizes that shutting down the government over a pet project amid a still-unfolding national crisis in Texas would be poor stewardship of the country.

All signs point toward the White House agreeing to sign a three-month stopgap funding bill without wall money. The shutdown fight would be postponed, then, to December, when Congress will engage in a larger appropriations battle over the rest of the fiscal year’s funding. (Though a shutdown in December would still not be “fun” for the country, at least it wouldn’t be tied up with a far more dangerous debt ceiling fight.)

The only thing that could derail this defusing of tensions is Trump changing his mind in an instant. Who’s to say that on the day Congress plans to move its stopgap bill, Trump won’t tweet a veto threat at 6:30 a.m. because some dingbat on Fox & Friends suggested he might look weak? You can’t say that. I can’t say that. No one can say that.

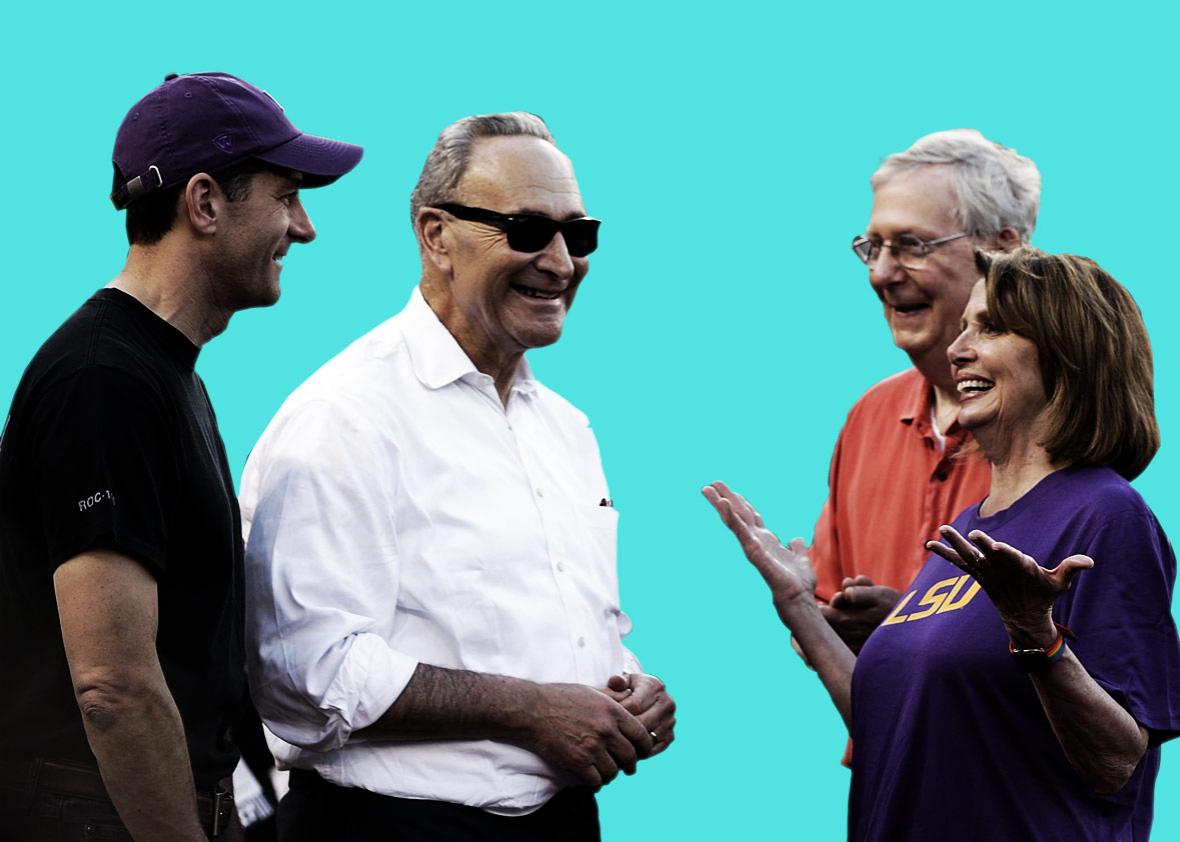

How seriously does Speaker Paul Ryan take Freedom Caucus threats?

The great thing about bipartisan legislation—such as either a “clean” stopgap spending bill, or a “clean” debt ceiling hike, meaning bills that aren’t mucked up with extra provisions—is that leaders don’t need to worry about appeasing irritating voting blocs within their caucus in order to get a majority of votes. When Speaker Paul Ryan was trying to pass party-line legislation to repeal Obamacare, he was left to the whims of the Freedom Caucus, and those guys know how to wield their leverage. If you have the votes of a whole other party to play with, you don’t need to worry about servicing 40 or so ideologues.

The only leverage those ideologues can wield, then, is threatening the speaker’s job.

Some Freedom Caucus members have threatened that if Ryan were to move a “clean” debt ceiling bill to the floor—i.e., one without corresponding reforms or spending cuts, like the most conservative in his party want—he might not be able to rely on the Freedom Caucus’ support for his job. Freedom Caucus Chairman Mark Meadows, in an interview with the Washington Post last week, warned leaders against logrolling Harvey relief and a debt ceiling hike into the same package, which leaders are very much thinking about doing. “The Harvey relief would pass on its own,” Meadows said, “and to use that as a vehicle to get people to vote for a debt ceiling is not appropriate.”

Ryan could bring a clean debt ceiling bill (and whatever’s attached to it, like Harvey aid) to the floor and likely pass it with the aid of Democrats’ votes. It would save him a lot of drama, but it would hurt his standing among conservatives. It’s his choice to make.

Will Democrats make demands?

We sort of assume that Democrats won’t go out of their way to be annoying on these must-pass bills. Usually if a “clean” bill, for either a continuing resolution or a debt ceiling increase, is on the table, they’ll vote yes. It’s not in their nature to push for brinksmanship, especially on the debt ceiling.

Two things, though.

Democrats understand that they have leverage on the funding bill. If there’s a shutdown, voters will most likely lay blame on the unified governing party for incompetent management. And though shutdowns suck, they’re not the end of the world. So Democrats have all the incentive to make demands of their own, at the very least to apply countervailing pressure against Republican demands.

Breaching the debt ceiling would be more akin to the end of the world, and Democrats are more hesitant to wield it as leverage because they understand that. But they also don’t want their votes to be taken for granted. And reasonably enough. Typically the governing party is the one that sucks it up and provides most of the votes for raising the debt ceiling. If Speaker Ryan comes to Democrats asking for a bailout because he can’t get his party in line, it makes good sense for Democrats to demand something in return.

In my conversations with Democratic aides this week, they’re keeping their powder dry, saying that they’ll make decisions on how to play this once Republicans come forward with an offer. One point they make is that they don’t want to provide free votes to lift the debt ceiling knowing that Republicans then will immediately pivot to blowing up the deficit via tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations. I don’t know exactly what they can extract via this messaging—get Republicans to promise … not to pursue their signature legislative goal of tax cuts?—but they will at least try to create the appearance that their “yes” votes can’t be assumed. Still, it seems difficult to imagine that Democrats would really try to play hardball over the debt ceiling in the end. They’re Democrats!