Want to listen to this article out loud? Hear it on Slate Voice.

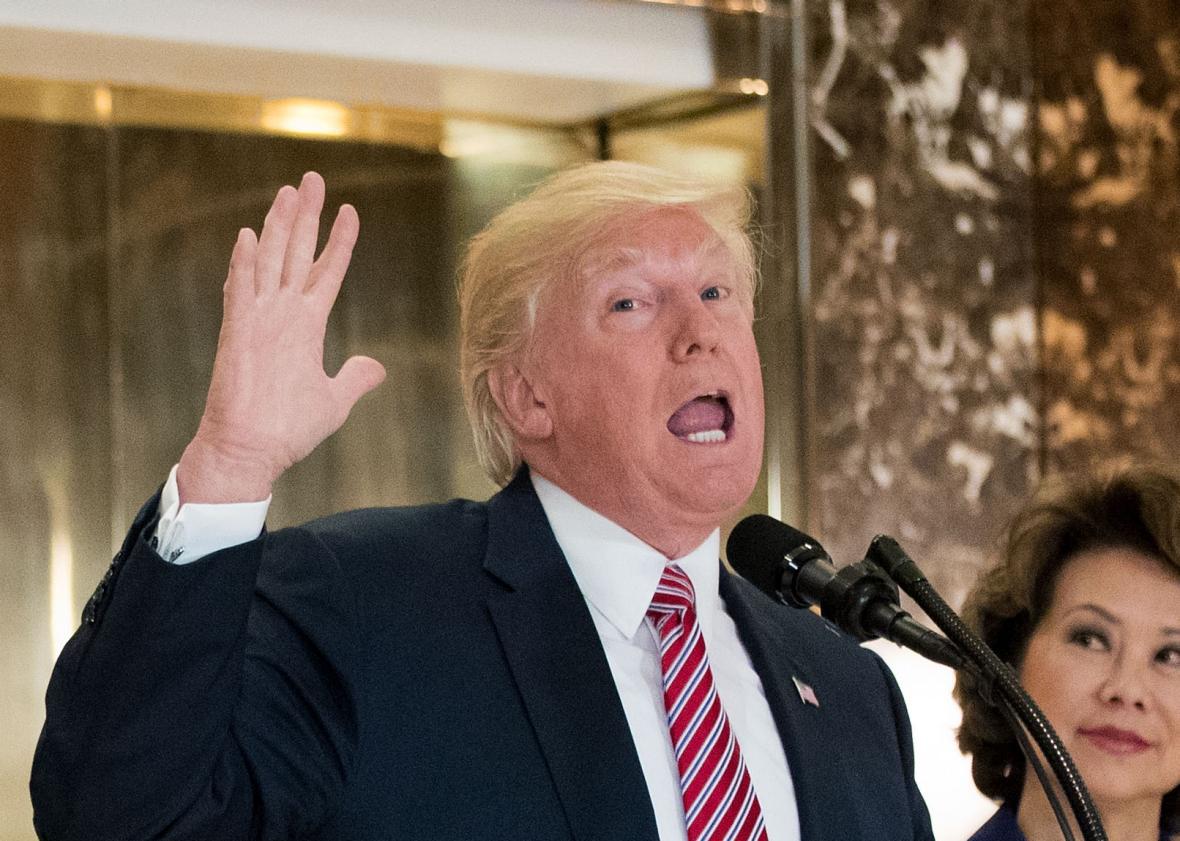

Donald Trump’s press conference on Tuesday afternoon, a defense of his own words and actions after this weekend’s deadly Charlottesville protests, was crazily unhinged even by Donald Trump standards. “What about the alt-left that came charging at the—as you say, the alt-right?” he asked, badgering a roomful of stunned reporters. “Do they have any semblance of guilt?” He also noted that there were “some very fine people on both sides,” an odd way to recap a rally in which a white supremacist killed a peaceful protester.

Trump, who has always loved an unnecessary wall, spent much of his time on Tuesday drawing conceptual borders. “Not all of those people were white supremacists, by any stretch,” the taxonomizer in chief explained. “Those people were also there because they wanted to protest the taking down of a statue, Robert E. Lee. You look at some of the groups and you see—you know it if you are honest reporters, which in many cases you are not—but many of the people were there to protest the taking down of the statue of Robert E. Lee. This week it’s Lee. I noticed that Stonewall Jackson is coming down. Is it George Washington next week, and Jefferson the week after?”

There is a meaningful distinction, he suggested, between a white supremacist and someone willing to march alongside white supremacists to preserve a white supremacist symbol. That’s a very fine-grained contrast for such an unsubtle man! And yet Trump sees no difference between Robert E. Lee, who committed treason to enshrine a system of human bondage in law forever and ever, and George Washington, who owned slaves but also helped invent the United States. It’s hard not to grasp the line separating the father of our country from a man who sought to destroy it, unless you’re a simpleton or a racist or … I’ll admit I’m fresh out of plausible descriptors here.

Trump’s defense of statue lovers was likely motivated in part by the protesters who gathered in Durham, North Carolina, on Monday night to topple a Confederate monument. The bronze plinth, erected in 1924, valorized a young soldier in the Southern army. It said on its base: “In memory of the boys who wore the gray.” The crowd looped a yellow nylon rope around the soldier’s neck and tugged, sending him careening headfirst into the grass, where men and women spat on him, kicked him repeatedly, and posed next to his crumpled form. Chants of “No Trump, no KKK, no fascist USA” soaked the summer air.

The spectacle of a mob having its way with a flimsy, puckered scrap of metal felt at once shocking and cathartic, a communal rejection of bigotry and an instance of everyday Americans stepping up where the government had fallen short.

Unlawful! Trump might have thought. Obscene! It is not surprising that the president would identify with antiquated images of white supremacy resting uneasily atop their pedestals. Our 45th president has much in common with these shoddy Confederate icons, relics that veil their hateful message in fake visions of a glorious past.

As multiple outlets have already pointed out, most of the roughly 1,500 Confederate monuments across the country were built decades after the Civil War ended. They were mass-produced cheaply in Northern factories between 1900 and 1930, then installed throughout the South to beguile nostalgic whites into supporting Jim Crow segregation. Often, as the historian Lola Arellano-Fryer writes in Hyperallergic (drawing on research by Sarah Beetham), these mail-ordered, anonymous effigies stood in “parade rest,” “a pose assumed by soldiers during ceremonial occasions.”* They were formed from bronze or cast zinc, known euphemistically as “white bronze,” and—because not much care went into their assembly—anchored only lightly to their plinths, making them easier for protesters to drag down.

Perhaps we should grant Lost Cause memorials the same reverence that their primarily Yankee manufacturers did. Durham’s soldier and Charlottesville’s Lee are bargain-bin racist tchotchkes, ensconced in our cities as tributes to a past that never was.

As the Republican nominee, Trump promised to return the nation to those utopian, non-existent days of yore. His vow to Make America Great Again weaponized nostalgia, using it to mask his fundamental immorality and incompetence. The president shares an aesthetic with the shabby, militaristic, ideologically rotten monuments he spent Tuesday afternoon defending. Let them all fall together.

*Update, Aug. 16, 2017: This article has been updated to acknowledge Sarah Beetham’s important work on Lost Cause sculptures, which informed the Hyperallergic piece used as a source. (Return.)