On Tuesday, President Donald Trump took a reprieve from the chaos engulfing his administration, traveling to Youngstown, Ohio, to commune with his fans and supporters in a campaign-style Make America Great Again rally. The event was typical Trump fare: exuberant and improvisational, with the occasional feel of a tent revival. And Trump brought his greatest hits, blasting Democrats, the news media, and other opponents for the crowd’s enjoyment.

The president also addressed immigration, and there his rhetoric took a darker turn. Trump has always described unauthorized immigrants in harsh, disparaging terms. But here he went further, spinning a lurid and explicit tale of extreme violence against innocent people.

“You’ve seen the stories about some of these animals,” said the president.

They don’t want to use guns, because it’s too fast and it’s not painful enough. So they’ll take a young, beautiful girl—16, 15, and others—and they slice them and dice them with a knife because they want them to go through excruciating pain before they die. And these are the animals that we’ve been protecting for so long. Well, they’re not being protected anymore, folks.

It’s easy to file this under Trump’s usual anti-immigrant demagoguery, specifically his preoccupation with crime committed by Hispanic immigrants. Recall his presidential announcement speech, where he assailed the Mexican government for sending criminals and “rapists” to the United States, as well as his (and Attorney General Jeff Sessions’) recent fixation on MS-13, a gang with origins in Central America. In a June rally in Iowa, the president stated that they “like to cut people,” and on Thursday, he mentioned them in a tweet: “Big progress being made in ridding our country of MS-13 gang members and gang members in general. MAKE AMERICA SAFE AGAIN!”

Despite the connection to those earlier statements, the Youngstown riff was different. It was especially detailed and graphic. And while the racial content of this kind of rhetoric has always been clear—the immigrants are always nonwhite, the victims are typically white—this was unusually explicit. Trump wasn’t just connecting immigrants with violent crime. He was using an outright racist trope: that of the violent, sadistic black or brown criminal, preying on innocent (usually white) women. Even considering his 1989 jeremiad against the Central Park Five—where he demanded the death penalty for the five black and Latino teenagers wrongly convicted of raping a white woman—the Youngstown rhetoric was sensational and excessive.

What it wasn’t, however, was unique. Rhetorically, Trump’s Youngstown speech recalls the openly racist language found in the early 20th century among white reporters, pamphleteers, and politicians who expressed the prejudices of the era. In Southern newspapers, for example, writers described the alleged crimes of black offenders with gruesome and sensational detail, usually to justify lynchings and other forms of extrajudicial violence. “A miserable negro beast attacked a telephone girl as she was going home at night, and choked her,” reads a 1903 report from a newspaper in Greenville, Mississippi. The writer of a 1914 pamphlet titled “The Black Shadow and the Red Death” spun terrible tales of black crime, including one where “cocaine and whiskey” led a “half-drunken negro beast” to kill a “little school girl” with a “pretty head.”

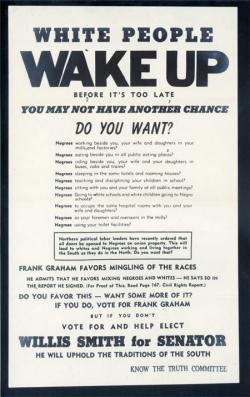

Politically, what President Trump was doing in Ohio has a clear antecedent in the racial demagoguery common in the Jim Crow South. Rather than campaign on what they would do for voters, Southern politicians fanned flames of race hatred. This “nigger baiting”—labeled as such by observers at the time—was how they built emotional connections with their audiences and tarred their (often equally racist) opponents as unacceptable proponents of racial equality. “You people who want social equality vote for Jones. You men who have nigger children vote for Jones,” declared South Carolina Gov. Coleman Livingston Blease in his 1912 re-election campaign against state Supreme Court Justice Ira Jones, blasting his opponent as a supporter of rights for black Americans.

Creative Commons

Lawmakers like James Vardaman in Mississippi and “Cotton Ed” Smith of South Carolina earned national notoriety for their vicious advocacy of white supremacy on the campaign trail. This style of politics did not end as the 20th century progressed; in 1958, Alabama Attorney General James Patterson ran for governor and won—beating a fresh-faced George Wallace—as a staunch opponent of civil rights, backed by the state’s Ku Klux Klan. In two re-election races, one in 1984 and the other in 1990, North Carolina Sen. Jesse Helms ran race-baiting campaigns. Against then–Gov. Jim Hunt, he distributed literature warning of black registration drives and black political figures such as Jesse Jackson. And against Harvey Gantt, the black mayor of Charlotte, Helms ran one of the most breathtakingly racist ads of the modern era.

Trump isn’t yet running for re-election, but he is in dire political straits. According to FiveThirtyEight’s aggregate measure of his popularity, just 38.5 percent of Americans approve of his presidency, compared with 55 percent who disapprove. He’s caught in a feud with his attorney general, there’s in-fighting among his senior staff, and he’s facing backlash from within the armed services on account of a cynical attempt to stoke anti-transgender bias for political gain. It’s possible, perhaps even likely, that the president’s riff in Youngstown was just another digression, a rant that emerged from the stew of resentments and prejudices that seem to form Trump’s psyche.

But the additional timing of his statement on transgender service members suggests otherwise. On Friday Trump will visit Long Island, where 15 members of MS-13 were arrested—a trip that would fit a political plan to demagogue Hispanic immigrants as imminent threats to white Americans, and white women in particular. Trump is aware that he’s flailing, and to rebuild support—to re-establish that bond with his voters—he’s turning to an old, crude, and dangerous rhetorical well.