To Democrats, the case against the Republican health care bill is simple. The Congressional Budget Office has found, on more than one occasion in assessing more than one version of the proposal, that it will leave far fewer Americans with insurance coverage than under the Obamacare status quo. Republicans have countered that the CBO has been wrong before and that its assessment of the bill is way too harsh, mostly because it greatly overstates the effectiveness of Obamacare’s individual mandate. Let’s assume for the moment that Republicans are right and that the Better Care Reconciliation Act will cover more people than the CBO projects. In that hypothetical world, we would know one thing for certain: The GOP effort to replace Obamacare would also cost far more than the CBO projects.

Consider that Obamacare wound up costing considerably less than the CBO assumed when it was first proposed, mostly because it wound up covering fewer people than expected. Obamacare’s true believers weren’t exactly thrilled that the Supreme Court stepped in to make it easier for states to refuse to accept the Obamacare Medicaid expansion or that large numbers of healthy young people chose not to sign up for coverage on the exchanges. Nevertheless, both developments meant the federal government wound up spending fewer dollars subsidizing health coverage than would have been the case otherwise. If you care first and foremost about expanding coverage, this is small comfort.

As a general rule, most Republicans are not primarily motivated by a desire to expand coverage partly because conservatives are more skeptical about the benefits of doing so. The problem with Obamacare is that it made big government bigger. If it turns out the GOP’s Obamacare replacement doesn’t lead to a steep drop in federal spending, well, what was the point?

This underscores the problem facing Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell as he tries to corral 50 votes for the BCRA. Faced with moderate and conservative senators who are inches away from jumping ship, he’s being forced to plow the budgetary savings scored by the CBO into sweeteners like extra funding to combat opioid abuse or to help low-income households afford their coverage. Again, if the CBO is underestimating the number of people the BCRA will cover, the savings the BCRA will supposedly bring are already illusory. The more sweeteners McConnell throws in, the more likely it is that the bill will actually increase the deficit.

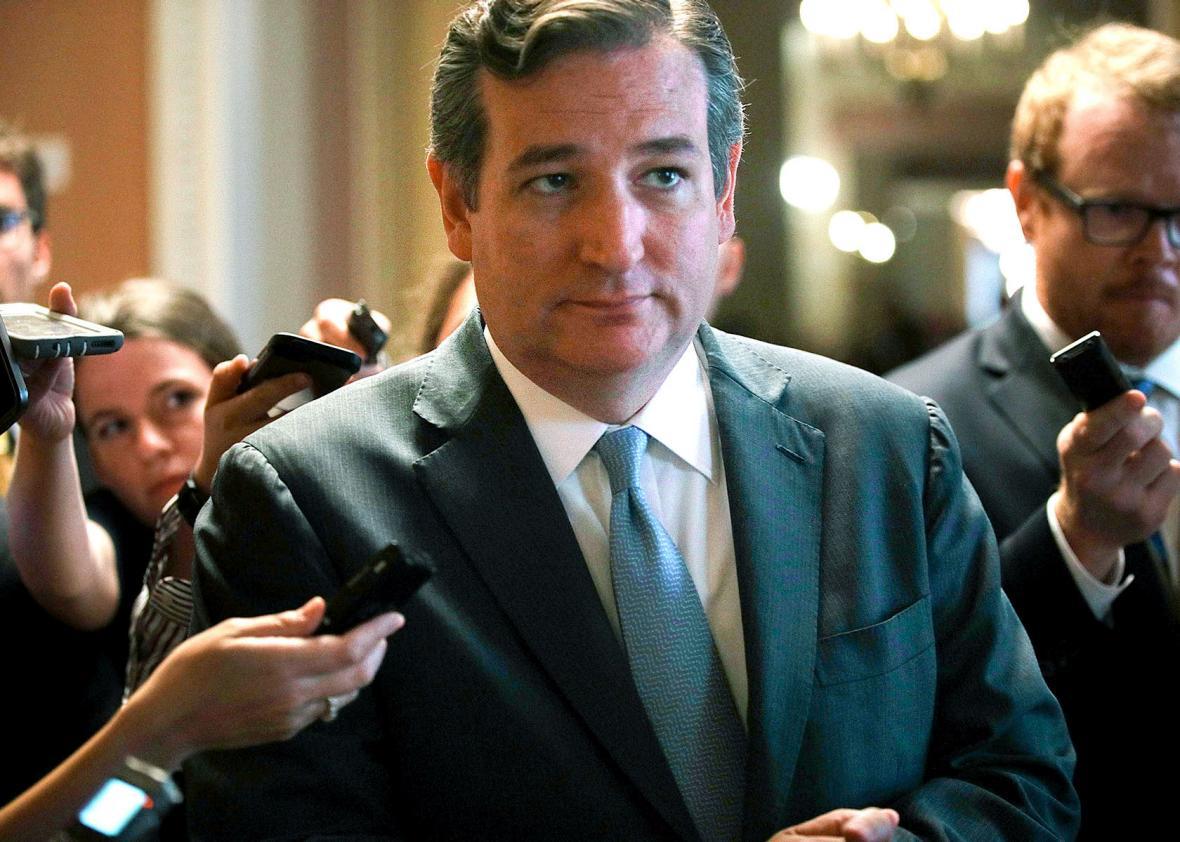

I see two ways forward for the GOP. The first would be to go all-in on Texas Sen. Ted Cruz’s “consumer freedom option.” The basic idea behind Cruz’s proposal is that as long as insurers sell Obamacare-compliant insurance policies, they’d also be free to sell non-Obamacare-compliant policies. McConnell has incorporated a version of Cruz’s proposal in the latest version of the BCRA, but it’s caused more confusion than anything else. The fear is that Cruz’s approach would lead younger healthier consumers to flee Obamacare-compliant policies for cheaper non-Obamacare-compliant policies, which would drive premiums on those non-Obamacare-compliant policies through the roof. Cruz is trying to allay the fears of GOP senators by telling them this isn’t so—that everyone would be included in a single risk pool. But it’s not clear how this would work in practice.

Republicans could just accept that Cruz’s consumer freedom option would fragment the risk pool. Over time, Obamacare-compliant plans sold on the exchanges would be a safety net for the poor and the sick, who’d receive the subsidies they need to afford their (expensive) coverage, while the rich and the healthy would buy unsubsidized non-Obamacare-compliant plans. There’s only one problem here, which is that the subsidies for the poor and the sick on the exchanges would have to be very large to ensure their coverage is affordable. The BCRA’s cuts to cost-sharing subsidies would have to be reversed. Short of that, Cruz’s safety net wouldn’t be much of a safety net at all. Over the long run, this safety net approach might save money, especially if the unsubsidized market succeeds in lowering costs and winning over a growing share of consumers. But it’s also possible this approach will cost just as much money, if not more. Either way, a deregulatory approach wedded to a reasonably strong safety net could bridge the gap between GOP conservatives and moderates.

The second way forward would be to give up on uniting Senate Republicans to pass a bill through reconciliation and instead try to woo enough Senate Democrats to win a filibuster-proof majority. Over the past few days, South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham and Louisiana Sen. Bill Cassidy have been touting their Graham–Cassidy amendment, which would preserve almost all of Obamacare’s taxes and then block grant the money to the 50 states to expand insurance coverage and otherwise shore up their insurance markets. In theory, liberal states could push further in the direction of single-payer while conservative states could embrace more market-friendly approaches.

It’s hard to imagine that Graham–Cassidy would pass muster under the rules of budget reconciliation, as it does much more than just tweak how the federal government spends money. Moreover, Graham–Cassidy is exceedingly vague in its current form, and it’s not at all clear what it would do to federal Medicaid spending, which is one of the most contentious aspects of the current health policy debate. It is, however, a politically palatable approach that dovetails with the conservative fondness for federalism. And its vagueness on Medicaid might help peel off a handful of red-state Democrats. For example, Republicans could adopt the “blended rate” approach to Medicaid spending first proposed by the Obama White House—this would be less effective at reining in federal Medicaid spending than the per-capita caps proposed in the BCRA, but it would also be less polarizing.

Honestly, neither of these ways forward are all that promising. It just so happens that McConnell is running out of options.