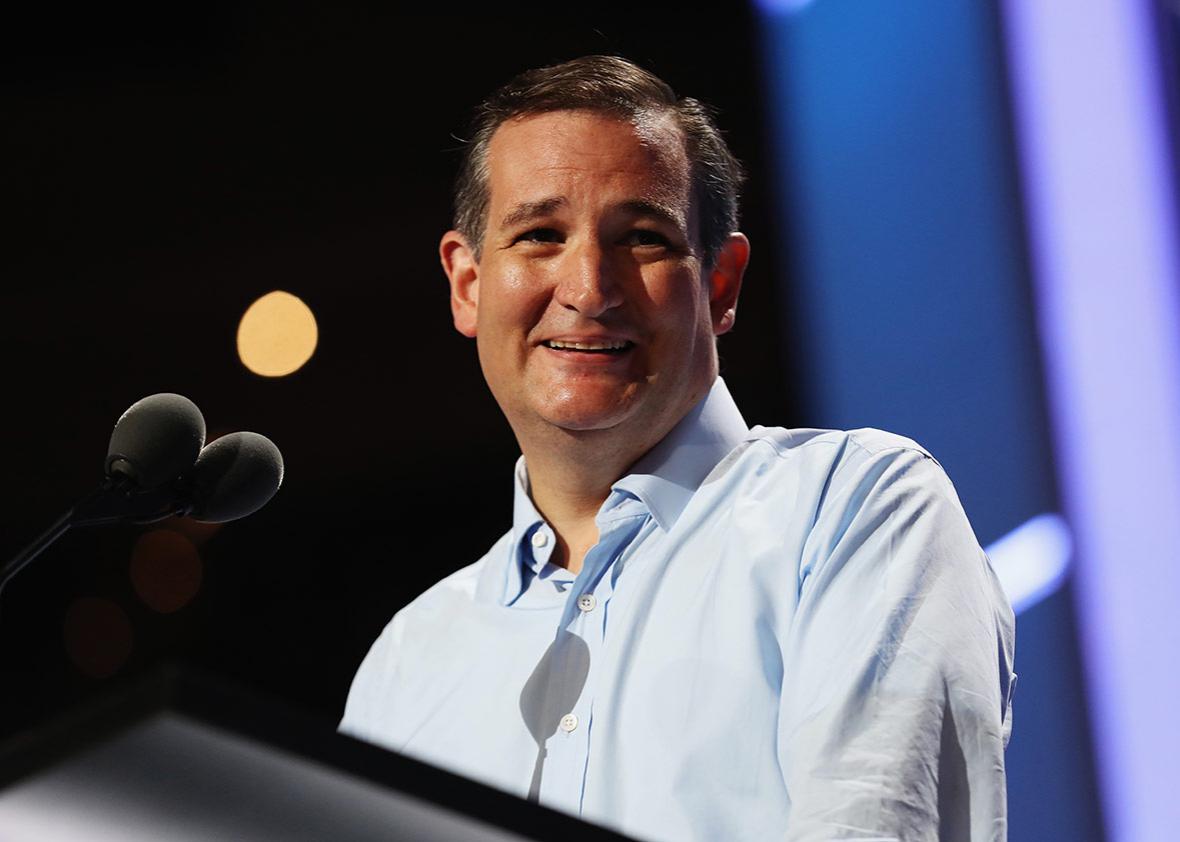

The key, now, to passing the Senate health care bill is winning over the votes of at least Texas Sen. Ted Cruz and Utah Sen. Mike Lee. The key to winning over Cruz and Lee is to include Cruz’s “Consumer Freedom” amendment in the bill, which would allow insurers to sell individual market plans that don’t comply with Obamacare’s regulations so long as they also sell at least one plan in the same market that does. And the key to getting Cruz’s amendment in the bill is to ensure that it won’t scare away more votes than it gains.

The Cruz amendment, as currently proposed, would cause too many moderates to flee, since it would undermine pricing protections for those with pre-existing conditions. Because young and healthy people would opt for the cheap, skinny, noncompliant plans, the risk pools for Affordable Care Act–compliant plans would fall out of balance, and premiums could spiral out of control as only the sickest people signed up for them. Though people making up to 350 percent of the federal poverty line (about $40,000) would be insulated from those premium increases with the aid of federal subsidies, those above that line who wanted compliant plans might have to pay, say, infinity dollars in premiums. The Cruz amendment, in short, sets up a classic adverse selection problem that could price those with pre-existing conditions out of the market.

But since this amendment is what Cruz and Lee have named as their price, Senate leaders have to find a way to let them have it—but with some adjustments to ensure that it doesn’t scare off moderates, vulnerables, and really any senators concerned about sustainable insurance markets. Resolving the conundrum Cruz’s amendment presents is now a central debate among Republican senators as they round up members for a vote next week.

One option that’s gaining steam, because it sounds like it could work in the abstract, is being pushed by South Dakota Sen. Mike Rounds. Though nothing’s been put to paper yet, the idea would be to link the prices of the compliant and noncompliant plans by a ratio to prevent the ACA plans from spiraling in cost while the “Cruz plans” remain nice and cheap.

“I talked to Sen. Cruz a couple of weeks ago about it and told him I would support it as long as there are provisions built into it so long as there is a ratio, a specific ratio, between the least expensive plan and the most expensive plan that any insurance company offers,” Rounds told reporters Monday afternoon. “And if [insurers cut the price on a cheaper] pool, they have to cut the price on the most expensive pool as well.” In other words, Rounds wants to keep the sicker pools tethered to the healthier pools, so insurance companies couldn’t keep premiums low for the plans healthy people want to buy while allowing premiums to skyrocket for the Obamacare plans sick people need.

The idea quickly gained traction among desperate Senate leaders trying to count votes. When I saw Senate Majority Whip John Cornyn in the hallway shortly after speaking to Rounds, he mentioned that he had also just been speaking to Rounds and seemed quite taken with his proposal.

“He said he thinks that doing something like that would be workable, you could offer lower-cost policies, but they would be connected to the higher-cost policies,” he said.

So would Rounds’ idea be something the GOP leadership would look at?

“Believe me, we’re looking at all angles, all options,” he said. By Tuesday, other members of the Senate leadership, including Missouri Sen. Roy Blunt and South Dakota Sen. John Thune, were speaking highly of it.

It remains to be seen if moderates will like the Rounds idea, and it’s tricky to gauge how well it will work before it’s committed to paper with specifics. I called health care expert Larry Levitt, senior vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation, to get his thoughts. He said the most glaring obstacle seems to be that that it would be difficult to link such unlike products operating under their own set of rules. Tethering highly regulated plans to wholly unregulated plans could be like tethering a hot-air balloon to Jell-O.

“You have two pools with, potentially, completely different populations and completely different benefits,” he said. “So kind of linking those premiums together would require a pretty significant regulatory apparatus.” Cruz, who wasn’t very forthcoming when I asked him about the idea on Monday, might not care for a change to his amendment that comes with a significant regulatory apparatus attached.

Another approach to containing the costs of the regulated pools, Levitt said, would be to transfer money from low-risk pools to high-risk pools. This is similar to the “risk-adjustment” transfers that currently occur under Obamacare, but doing it between regulated and unregulated plans would be harder.

“The way risk adjustment works [under Obamacare] is that each insurer gets a score based on the risk of its population,” Levitt said, but they’re offering plans with the same benefits. So “how do you assign a score,” to use one hypothetical, “to one plan that covers prescription drugs and another plan that doesn’t?”

Senate leaders have sent the current iteration of the Cruz amendment to the Congressional Budget Office to be scored. If CBO finds that the amendment would skyrocket premiums for the ACA-compliant pools, leaders will have to either dramatically subsidize those with pre-existing conditions or come up with a fix that contains costs, like the Rounds idea—or whatever else anyone can come up with in a few days’ time. The former would amount to throwing money at a policy error. Since “throwing money at policy errors” is the unofficial slogan of the United States government, it can’t be ruled out. Especially since the policy fix, as with all health care issues, is still elusive.