OK, everyone: James Comey gave his testimony. He did it. It’s over now. Time to move on. Good? Good. Because while that was going on, Senate Republicans moved closer than ever to garnering the support they need to pass a health care bill.

This doesn’t mean that no serious disputes remain. Those disputes, however, seem to be of a second order, with broad agreement on the underlying structure of the bill.

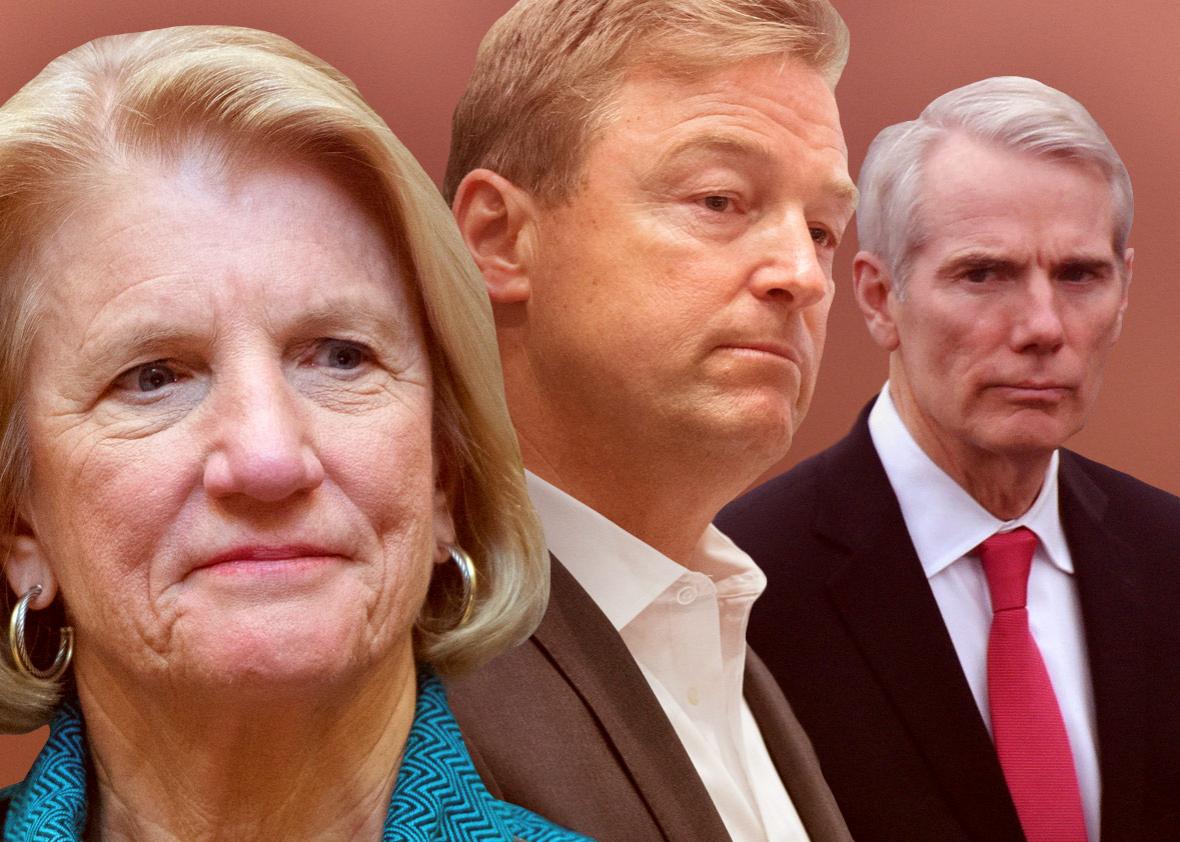

Like the House, the Senate intends to cut Medicaid. Unlike House members, though, senators are at least sensitive to the impression that they’re looting Medicaid for as much money as they need to fund tax cuts. While the House-passed American Health Care Act would abruptly end the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion in 2020, the Senate will likely take a more palliative approach. Leadership reportedly wants to phase out the Medicaid expansion over three years, beginning in 2020. The senators from Medicaid expansion states that have been most wary of rolling it back, including Ohio Sen. Rob Portman, West Virginia Sen. Shelley Moore Capito, and Nevada Sen. Dean Heller, are asking for seven years. But they still seem on board with the premise of rolling it back.

Another dispute involves the growth rate that would be applied to the new Medicaid system. Like the House, the Senate intends to convert Medicaid from its current open-ended federal match rate structure to one of per capita spending caps or block grants, either of which set finite amounts to federal Medicaid spending. The question is by which inflation measure these set amounts will grow. The House bill uses the medical component of the Consumer Price Index, with higher rates for certain classes of beneficiaries. Conservatives would prefer a slower growth rate, like standard CPI—a proposal Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney made in President Trump’s recent budget proposal—while Sen. Heller says he wants one in line with projected medical spending. Senate Majority Whip John Cornyn told Talking Points Memo that for now, they have this item “marked ‘TBD.’ ”

These may sound like small issues, but they’re not—especially the growth rate question. A seven-year phaseout of the Medicaid expansion might dull the pain more than a three-year-phaseout, but the Medicaid expansion will be phased out either way. If senators opt for a growth rate considerably slower than projected medical inflation, Medicaid could eventually wither on the vine.

But do these sound like items that might tank Congress and the president’s signature legislative item, on which they’ve already spent five critically important months? Or does it sound like senators are just working through the final details? As Sen. Capito—who’d previously not been comfortable with rolling back the Medicaid expansion—told the Washington Examiner this week, the Senate GOP is “getting down to the nitty gritty.”

If Capito thinks they’re “getting down to the nitty gritty,” that means there’s consensus on the underlying structure.

Though some senators may not like the idea of tying off the Medicaid expansion and overhauling Medicaid’s structure in a way the Congressional Budget Office says will remove millions of people from the health care roll, they’ll apparently do it in order to pass a bill. Any remaining disagreement will revolve around the finishing touches.

There is still vigorous debate over the ACA’s health insurance regulations, too, and which ones the Senate version bill will allow states to waive. Essential health benefits? Community rating by health status? How much more insurers can charge old people than young? Some conservatives may want all of these regulations to be optional; some moderates may not want any of them. They might settle somewhere in the middle.

(There is also a technical question about whether certain anti-abortion language can pass under Senate reconciliation rules. Of course there is! It wouldn’t be a piece of must-pass legislation if there weren’t a news cycle about how Abortion Provisions Could Doom Must-Pass Bill. They’ll figure this part out.)

Who knows what the final combination of these elements will be in the Senate’s proposal? Perhaps a five-year Medicaid phaseout, the same growth rate as the House bill, and waivers on age rating and essential health benefits but not the community ratings that impact people with pre-existing conditions. Or a three-year Medicaid phaseout, a higher growth rate, and waivers on community rating, age rating, and essential health benefits, with more money spent upfront to stabilize insurance markets over the next two years.

But by all accounts, it really is a matter of finding that combination that hits the sweet spot. The structure is in place, and senators are beginning to fall in line. The House bill was never dead on arrival in the Senate; it was just going to get a touch-up. Trumpcare is on the move.