Prior to Tuesday’s Republican caucus lunch, South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham was despondent about health care reform’s chances of passing the Senate this year.

“I don’t think there will be” a bill passed in 2017, he said on Monday. “I just don’t think we can put it together among ourselves.” He continued Tuesday morning. “We’re stuck. We can’t get from there to here.”

Graham wasn’t the only senator preparing to entomb the effort. North Carolina Sen. Richard Burr told a local news station that he didn’t see the Senate passing “a comprehensive health care plan this year.” And Wisconsin Sen. Ron Johnson suggested that the Senate’s first priority should be a bill to stabilize insurance markets.

But senators’ reactions following the Tuesday meeting were considerably more optimistic. According to North Dakota Sen. John Hoeven, party leaders used that meeting to present “goals and then a number of different ideas on how to achieve them.” South Dakota Sen. Mike Rounds described it as “one of the best discussions we’ve ever had.” Even if they still have serious sticking points, Sen. John Boozman of Arkansas said, he’s “optimistic in that everybody wants to find a solution.”

Even Lindsey Graham appeared to have turned a 180 on his outlook.

“Promising, very promising,” Graham told reporters of the meeting as he was leaving.

Was he shown a single plan, or a menu of options for getting to a plan?

“A promising menu of options.”

So was there a PowerPoint of the menu or just chatter?

“A promising PowerPoint,” he said, tight-lipped about specifics.

If the goal on Tuesday was to relay bland happy talk to counter headlines from Monday like the one in Politico saying, “GOP Senators Offer Downbeat Predictions on Obamacare Repeal,” Senate Republicans may have achieved that. They have, at the very least, demonstrated a will from within the caucus to express a desire to finish this effort.

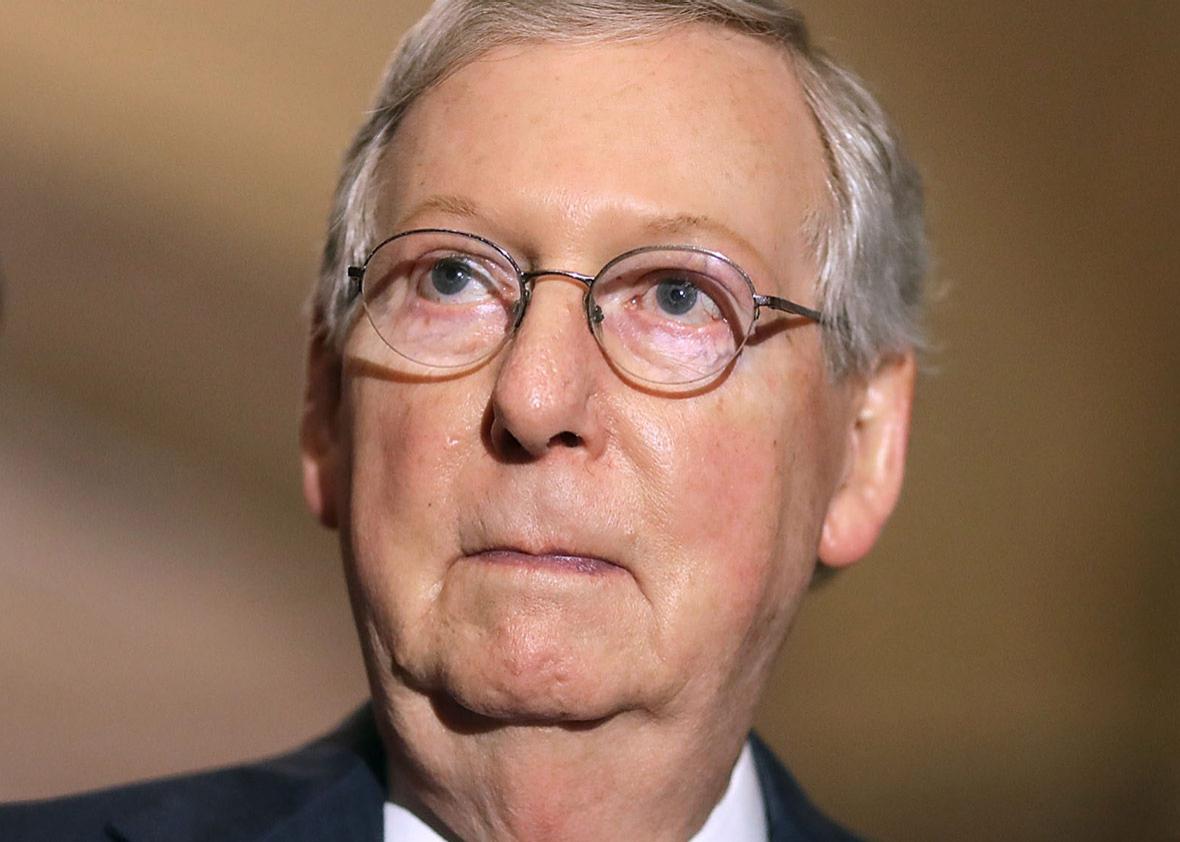

“We are getting closer to having a proposal,” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said at his press conference following the lunch, “and we’ll bring it up in the near future.”

As the exhausting House process to pass the American Health Care Act showed, the will to pass legislation can paper over a lot of fundamental differences. It can even get people to vote for a bill that they know is bad for their constituents and their careers. That the will appears to exist justifies Tuesday’s happy talk. But it does not reconcile differences that still exist and are not much closer to resolution.

It seemed at first like great news for the bill’s chances that Sen. Bill Cassidy, an outspoken moderate on health care, liked what he saw in the presentation at Tuesday’s meeting of the health care working group.

“Yes,” he said, when a reporter asked him if what he saw looked like a bill he could support, adding that “it’s very cognizant on pre-existing conditions.” If Cassidy liked the proposal, that was potentially a major development in ushering it toward a vote.

But just as with the writing of the House bill, every policy shift to win over one bloc threatens losing the other. If Cassidy liked what he saw, there would be problems elsewhere in the conference.

Axios reported that the presentation, which was later shared with the full Republican caucus during its regular Tuesday lunch, made a “firmer” recommendation on state deregulatory waivers than it did on some other issues. Like the House bill, the Senate proposal would allow states to waive the Affordable Care Act’s essential health benefit coverage requirements, as well as loosen the ratio of what older people can be charged relative to younger customers. The Senate bill would not, however, allow states to waive community rating by health status, which bars insurers from charging sick people more than healthy ones. The Washington Examiner reported, too, that the Senate was considering allowing the ACA’s Medicaid expansion to linger past the 2020 deadline set forth in the House bill—and that a program to auto-enroll people into coverage against catastrophic losses was still on the table.

Cassidy added that policies to stabilize health insurance markets in the short term would be rolled into the legislation. About “$15 billion a year for the first couple of years” would be appropriated to stabilize markets, which he said was close to what the actuarial company Milliman expected would be required. On top of that, Cassidy said, there was an “attempt” to appropriate the money for the ACA’s cost-sharing reductions, the payments the federal government makes to insurers to mitigate deductibles for low-income people. (The Trump administration’s ambivalence about whether it will continue to make these payments, which are subject to an ongoing legal dispute, has contributed to the cratering of certain states’ health insurance markets.)

In short: To the extent the bill is moving in any direction, it’s moving toward the center, making the sort of changes aimed at getting the likes of Cassidy on board and—at the very least—preventing the likes of Graham from preaching the bill’s death in public.

But just because Cassidy gets on board doesn’t mean that, say, Sens. Susan Collins or Lisa Murkowski, who have had few good things at all to say about this reform framework, are coming around. More problematically, the closer the bill moves to the center, the further away it moves from the bloc of conservative senators intent on pressing their leverage.

While Sen. Rand Paul’s vote is not quite “irretrievably lost” on the bill, as Graham had described it earlier, Paul’s office staff did not sound particularly enthusiastic about what they had just seen. “Sen. Paul remains optimistic the bill can be improved in the days ahead,” a spokesman said, “and is keeping an open mind.”

An aide to another conservative senator told me that the outline presented Tuesday had moved “further away” from the senator’s goals. I asked on which areas specifically: regulations? Medicaid?

“All the issues,” the aide said.

Tuesday’s presentation presented the moderates, the skeptics, the vulnerable members—in short, all of those who do not like legislating on health care and want this thing to just go away—with reason enough to stay on board. Happy talk, though, is not the same thing as an announcement that fundamental differences within the caucus have been reconciled.