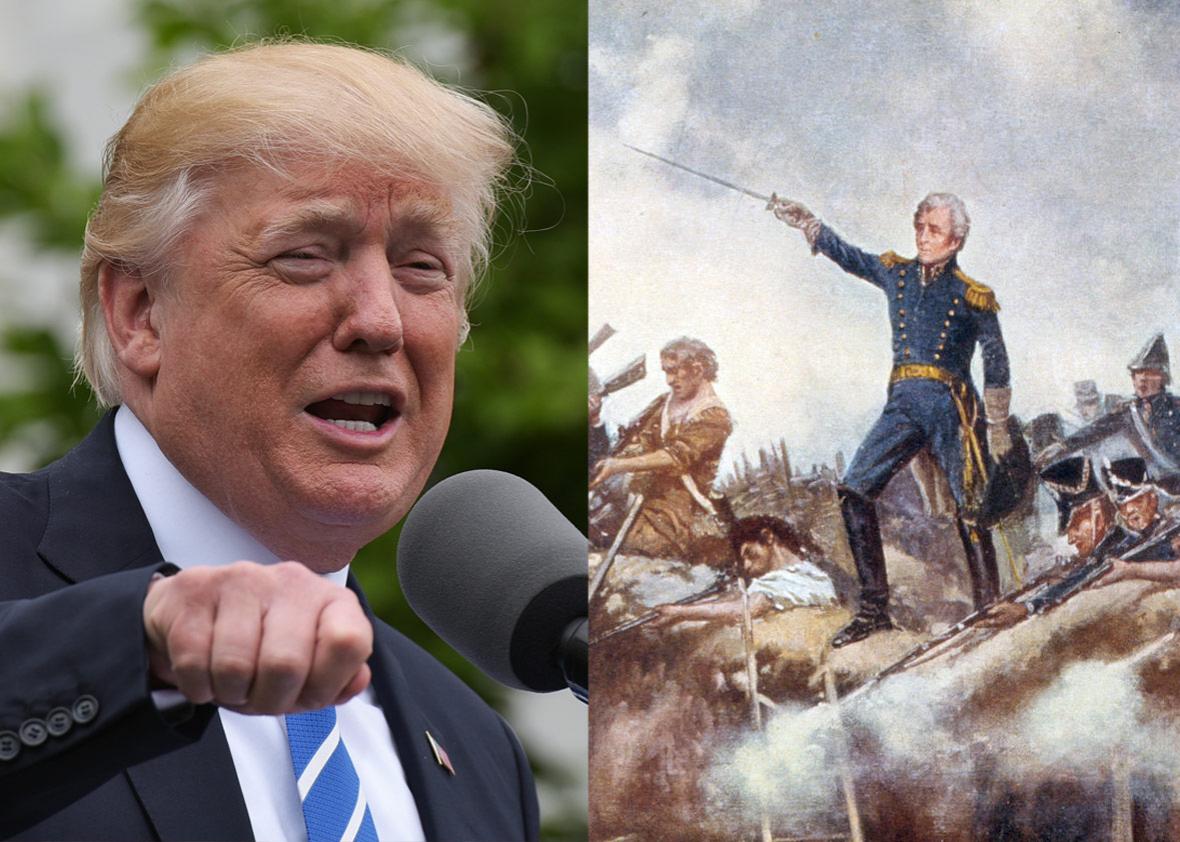

On Sunday, during an interview with conservative writer Selena Zito, President Trump channeled his inner Harry Turtledove with a small bit of alternative history. “I mean, had Andrew Jackson been a little later you wouldn’t have had the Civil War,” said the president. “He was a very tough person, but he had a big heart. He was really angry that he saw what was happening with regard to the Civil War, he said “There’s no reason for this.’ ”

The president concluded his riff with a question: “The Civil War, if you think about it, why? People don’t ask the question, but why was there the Civil War? Why could that one not have been worked out?”

There are too many threads to untangle from this dense knot of incoherence, from Trump’s claims about Jackson’s character and priorities to his ignorance of the Civil War and its causes, which he projects on unnamed “people,” seemingly unaware that this subject is among the most studied and debated in American historiography. Trump’s attempted alternative history is so remarkable that it’s tempting to ignore it as yet another bizarre claim from a president defined by his deep and abiding ignorance.

Then again, like so many Trump utterances, this one reveals something about the president. Several things, in fact. From Trump’s statement, we gain insight into his view of presidential leadership, his understanding of politics (broadly defined), and his sense (or lack thereof) of the fissures and moral conflicts in American society. For all the incoherence, in other words, Trump’s musing was actually useful, giving us a window into his mind and reminding us, as observers, that the most powerful office holder in the country is also entirely ignorant of the nation’s history.

But first, let’s address the facts of the president’s digression. Historians know what caused the Civil War, and the answer is as straightforward now as it was in 1861, despite generations of argument meant to muddy the waters: Slavery.

“One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest,” observed Abraham Lincoln in his second inaugural address, given as the war was drawing to a close in March 1865. “All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.”

The tensions that led to this point didn’t just emerge ex nihilo in 1861. Instead, they stretch back to the founding, when slaveholding elites—including key founders like Thomas Jefferson and George Washington—sought to preserve an institution that afforded them wealth, opportunity, and immense privilege. The end of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, along with rising demand for cotton, supercharged slavery in the first decades of the 19th century, entrenching its presence in the old South while opening new opportunities in slave-exporting states like Virginia. At the same time, this entrenchment drove a new politics of expansion, as planter aristocrats—backed by a burgeoning class of small landowners with modest investment in human bondage—demanded more land on which to ply their trade in human flesh.

This combination of shared economic interest and worldview made the planter class and its aspirants one of the most cohesive political units in early American politics, with an incredible hold on the levers of state and national power. They dominated Southern state governments and held disproportionate influence in the House of Representatives thanks to the Constitution’s Three-Fifths Compromise. “In 1815, they had held the presidency for twenty-two of the [previous] twenty-six years, and they would control it for all but eight of the [subsequent] thirty-four,” wrote historian Daniel Walker Howe in What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848.

The economic prospects of slavery and slaveholders only grew with the country’s acquisition of territory. The Louisiana Purchase opened vast regions to enterprising planters and merchants. Within 20 years of Jefferson’s diplomatic coup, Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana had been admitted to the Union as slave states. Likewise, successive presidential administrations—from Jefferson to Monroe—fought to capture Florida from the Spanish, partly out of concern for the nation’s southern border, and partly to stop the flow of black Americans to the territory, which had become a safe haven for escaped slaves and Native Americans fleeing oppression in the United States.

These years of growth and expansion strengthened the commitment to slavery from Southern elites. In 1820, Southern lawmakers stood unified against a proposal from New York Rep. James Tallmadge to ban the importation of slaves to Missouri as a condition of its statehood, and to mandate eventual emancipation for all children of slaves born in Missouri after it attained said statehood. Some slaveholders, including an elderly Jefferson, invoked the nation’s founding, blasting the proposal as an infringement on the constitutional equality of white Missourians. Others cited the need for a valve to drain excess slave populations from states like South Carolina—where enslaved blacks were nearly a majority of the total populace. Still others argued that the South needed as many markets for slavery and slave trading as possible, and Tallmadge’s proposal would have a dangerous precedent for the institution. Not least of all, gradual emancipation in Missouri would upset the balance of free to slave states, threatening planter power in the long-term at the level of Congress and the Electoral College.

Eventually resolved in a compromise that allowed slavery in Missouri but prohibited it in all Louisiana Purchase territories north of state’s southern border, the Missouri Controversy presaged future sectional tensions between an increasingly powerful South and a resentful North. Indeed, during one of the heated floor debates over Tallmadge’s proposal, Georgia Rep. Thomas W. Cobb warned that the New York lawmaker had “kindled a fire which all the waters of the ocean cannot put out, which seas of blood can only extinguish.” He was right. By the 1840s, planter elites would come to embrace slavery as a “positive good,” the term coined by John C. Calhoun, Southern statesman, slaveholder, and political theorist. Sectional tensions reached a fever pitch in the 1850s, following the South’s aggressive bid to secure the political future of slavery, and exploded toward the end of that decade with the formation of the Republican Party, the election of Abraham Lincoln, and the South’s decision to leave the Union rather than see potential limits placed on slavery’s expansion.

Which brings us back to Andrew Jackson, Donald Trump’s apparent inspiration, and a frequent reference point for the new president. Jackson—who found his success on America’s frontier, fighting in the War of 1812 and settling in Tennessee—was a planter with substantial slave holdings. For that reason, his sympathies lay with the Southern elites. As president, Jackson was an aggressive advocate for the economic interests of the planter class. His policies of Indian removal—covering Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and parts of Tennessee—opened new lands for white settlement, cotton cultivation, and the expansion of slavery. Jackson backed Southern efforts to suppress the circulation of anti-slavery literature, and fought hard to open foreign ports to American cotton exports.

At the same time, Jackson was a rigid unionist—an unyielding believer in popular sovereignty as expressed through democratically ordained leaders like himself. While Jackson’s democratic vision was unabashedly patriarchal and white supremacist, he had no love for the secessionist impulse of Southern political foes, which plagued his administration in its final years. A dispute over tariffs that fell hardest on South Carolina planters metastasized into a full-blown dispute over national power, when the most radical slaveholders advanced arguments for secession. Attempting to steer a course between extremists on one hand and his own unionism on the other, Calhoun—then Jackson’s vice president—advanced a theory of nullification, or the rights of states to nullify federal law it deemed unconstitutional.

In late 1832, as the tariff dispute advanced, South Carolina lawmakers passed an ordinance declaring the offending tariffs unconstitutional and forbidding enforcement within the state’s borders, effectively attempting to nullify federal law. Anticipating federal resistance, the state legislature raised a force of 25,000 militiamen, and Calhoun—a leading voice for nullification—resigned his position in Jackson’s government.

Jackson responded by condemning the nullifiers, reinforcing garrisons in the state, and threatening retaliatory violence, warning one South Carolina congressman that “if one drop of blood be shed there in defiance of the laws of the United States, I will hang the first man of them I can get my hands on to the first tree I can find.” Jackson’s larger argument was that national sovereignty was inviolable, and that “Disunion by armed force is treason.” Jackson’s congressional allies granted him power to deal with the crisis, and Kentucky Sen. Henry Clay—a frequent adversary of the president who had just lost the race for president on the National Republican Party ticket (not to be confused with the GOP)—crafted a compromise on tariffs that would defuse the crisis. Other Southern states declined to join this fight against the federal government; from his Indian Removal policy to his obvious support for white supremacy and slavery, most Southern leaders saw an ally in Jackson.

While nullification died as a viable strategy in the wake of the compromise and the resolution of the crisis, secession lived on, stoked by Calhoun and other “states-righters.” Jackson did predict that this wasn’t over—that, in the future, the radicalized planters of South Carolina would seize on “the negro, or slavery question” to advance their anti-union interests. Which is what would happen, nearly 30 years later.

Contrary to Donald Trump’s view, Jackson wouldn’t have said “what is the reason for this?” The answer, again, was plain. It was slavery and all the interests and disputes tied up in the institution. From Missouri to Nullification to the fierce battles over the Mexican War and the strife of the 1850s and last-ditch efforts to avoid conflict, slavery was the defining domestic concern of the antebellum United States, the dilemma that consumed the energy of the nation’s most able lawmakers and statesman, up until tensions exploded in open warfare. Donald Trump is apparently ignorant of all of this, but his alt-history musings aren’t necessarily unreasonable. Given what we know, what would Andrew Jackson have done in 1860 and 1861? Could it all have been “worked out,” to borrow the president’s words?

If you believe that slavery constituted an irrepressible moral and political conflict in the United States, then a war of some sort was likely inevitable. But that doesn’t mean it couldn’t have been postponed. There’s a case to make that a President Jackson in 1861 could have done just that, by bolstering the planter class and its search for new territories and new markets. This, in fact, was a live option in the timeline as it exists; unionist Democrats like Stephen Douglas, Lincoln’s chief opponent in the 1860 election, sought to preserve the United States through alliance with slaveholders and maintenance of a pro-slavery status quo. As chairman of the Senate committee on territories, Douglas helped craft the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which effectively undid a key provision of the Missouri Compromise (banning slavery in territories north of that state’s southern border) and organized two new territories—Kansas and Nebraska—that could choose to be slave or free. An almost unambiguous win for Southern slaveholders, Kansas-Nebraska would help push the sectional crisis to its breaking point. Likewise, as a presidential candidate, Douglas stood against Lincoln’s talk of a “house divided.” To talk about the end of slavery, he argued, was “revolutionary and destructive to the existence of this Government.” As Douglas declared in one debate, “I would not endanger the perpetuity of this Union. I would not blot out the great inalienable rights of the white men for all the negroes that ever existed.”

It is easy to imagine a President Jackson in 1860 who followed Douglas’ path. Who, in keeping with his sympathies and beliefs about Americans democracy, forestalled war by advancing the interests of slaveholders and Southern elites even further than Douglas proposed, opening new territories to the expansion of slavery, and organizing the nation’s foreign policy around new markets and opportunities for slave-produced commodities. Jackson may well have prevented the war, at the cost of 4 million black Americans, held in bondage.

That gets to the rub of it all. Trump isn’t wrong to think there was a deal that could have prevented the Civil War. There was. But the price of that deal was the maintenance of slavery; in fact, the strengthening of a monstrous system of violence and exploitation.

That this wasn’t obvious to President Trump—that, judging from his continued tweets on the issue, it still isn’t—is as revealing as it is troubling. It suggests a worldview in which everything can be resolved by deals, where there are no moral stakes or irreconcilable differences, where there aren’t battles that have to be fought for the sake of the nation and its soul. Slavery had to be eradicated, and war was the only option. Any deal that was achievable would have been an immoral maintenance of an abominable status quo.

Likewise, Trump seems to see presidential leadership as a game of dealmaking, where the best and most effective presidents are those that make the most “deals.” But this just isn’t true. Dealmaking and negotiation are part of the job of the presidency, but they have to happen with a purpose in mind; with an idea of the good within reach. Simply striking a deal for the sake of a deal is a recipe for terrible missteps or outright capture by antagonistic interests. Trump’s amoral and opportunistic approach may pay dividends in the world of real estate, but it can bring disaster in government, obscuring real challenges, alienating potential allies, and bringing bad outcomes.

Above all, Trump’s musings are a reminder that his ignorance isn’t an act or a performance. The president of the United States isn’t just inexperienced; he is profoundly unknowledgeable about his country and its history, as uninterested in the challenges of the past as he is the dilemmas of the present. He knows nothing of the world around him, other than the selected information he receives from his advisers, which then gets restated to us, the public, in often-garbled form.

This ignorance isn’t just embarrassing; it’s also a threat to our collective and institutional well-being. A president who knows nothing of the past will likely blunder in office; a president who knows nothing of history will likely repeat the worst mistakes of his predecessors; a president who all but relishes his ignorance will, at some point, lead us all into disaster.