On a Saturday afternoon in mid-March, Sean Spicer ran an errand at the Apple Store. There, arms laden with various chargers, he encountered a hailstorm of questions—far more aggressive than any he’d fielded in his weekday job as White House press secretary.

“How do you feel about destroying our country, Sean?” asked Shree Chauhan, an education policy worker who’d spied Spicer in his off-duty blazer and jewel-toned sport shirt and seized the opportunity to live-stream accosting him on Periscope. “Do you feel good about the decisions you’re making? Do you feel good about lying to the American people?”

Spicer parried the onslaught with a wan smile and mumbled non sequiturs. (At one point he muttered, “Such a great country that allows you to be here”—possibly an allusion to Chauhan’s skin color. She is Indian American and was, in fact, born here.)

The whole incident offered a glimpse into how a trained spokesman reacts when faced with untrained and unanticipated queries. Spicer didn’t look smooth and prepped. He got flustered.

Chauhan later wrote that she’d viewed her encounter in the wild as an opportunity “to get answers without the protections normally given to Mr. Spicer.” Which is sort of a strange thing to say, given that Spicer is in no way protected from facing questions. He spends most of his afternoons getting peppered with questions—it’s like the main thing he does.

Still, you get what she means, right?

There’s something about the pretense of the James S. Brady Press Briefing Room, where Spicer plies his trade. The pomp of the White House seal, the stately traditions of the West Wing. The self-imposed, collective restraint of a professional media corps—even in the age of Trump, not a no-holds-barred Shree Chauhan among them.

Since Jan. 20, Spicer’s press briefings have become must-see TV for 4.3 million Americans, many of whom tune in desperately hoping for the thrill of a confrontational moment. All the liberals I know are now press critics, screaming into their laptops, suggesting cleverly phrased questions the reporters should be asking instead of the apparently toothless ones they’re asking instead. My boss thinks the press should take off the gloves and attack! My colleagues want to ban multipart questions! And my friends seem to know exactly how they’d break Spicer, if only they could get inside the room.

Well, I got inside the room. I spent several weeks attending White House press briefings at the start of the new administration, camping out in the back, jammed against the wall, at one point with a Daily Mail reporter sitting on my feet. I wondered: Are we doing these all wrong?

* * *

White House press briefings have always been, on some level, silly.

“Day in, day out,” says a person who worked in a past administration and was closely involved in its briefing process, “they’re of precious little value. If a White House wants to get news out, a press briefing is not the venue it’s going to use. As a result, press secretaries mostly play defense. They’re trying not to make news or be pinned down.”

Quick, name a newsmaking moment from a pre-Trump press briefing—any administration, any press secretary. C.J. Cregg doesn’t count. Having trouble? That’s because pretty much nothing of import has ever emerged from a press secretary’s mouth.

Yes, Richard Nixon’s much-loathed mouthpiece, Ron Ziegler, famously dismissed Watergate as a “third-rate burglary” from the podium, excused his own exposed untruths as newly “inoperative,” and stuck with Nixon until the bitter end. But Ziegler was the comic relief of the Watergate saga. He color-commentated on events that had accelerated beyond him. None of the reporting that brought Nixon down happened in the briefing room.

Before Spicer came along, the most notable briefing brouhaha of this century took place on Sept. 26, 2001, when Ari Fleischer—the first press secretary of the George W. Bush administration—told terrorized Americans that “they need to watch what they say, watch what they do.” The remark got seized on by left-wing columnists as an Orwellian threat. But in context it was harmless. (Ted Koppel said so at the time, and Christopher Hitchens agreed five years later in a column for Slate.)

On the vast majority of days, the briefing is a weird Kabuki ritual in which little of worth is revealed. Reporters sit in the 49 seats—or, if you’re like me or one of the other schmoes, stand against the wall or in a rear corner—and endure several minutes of Spicer’s prepared, pro-Trump propaganda, in hopes that he’ll call on them once the Q&A time starts. The TV correspondents up front are aiming to provoke a colorful exchange that they can edit into a network news snippet or a viral social media clip. The print folks are largely resigned to getting reaction quotes, not new details. I suspect the real reason some outlets are there is simply for the White House dateline or the visual of the North Portico in the background of the stand-up shot.

Briefings are often—as the Ziegler example underscores—a means of obfuscating the truth. Which is, in itself, a reason to engage in the process. The daily briefing creates an iterative record that helps us read Oval Office tea leaves. Carefully crafted press secretary sound bites will suddenly change a little or go out of fashion. Arguments get added or dropped. Themes get stressed with more or less urgency. These are useful clues to understanding the behind-the-scenes machinations.

But perhaps the briefing’s greatest value is symbolic: The White House steps into the arena each day and engages with the press. “The idea is that they believe in their policies, so they’ll stand up and defend them. Interlocutors will present challenges in that room, and they will be answered,” says one White House reporter. “But every single aspect of that has been undermined by the Trump administration.”

* * *

Alex Wong/Getty Images

Some critiques of Trump’s press relations have been overblown. Access has in many ways been terrific so far—and that’s not even counting the gush of leaks. Trump invites reporters into the Oval Office more often than Obama did, and correspondents can randomly encounter the president and his senior aides while loitering in a nearby hallway—an area known as “upper press” that George Stephanopoulos, for instance, kept closed off to journalists during the Clinton administration. Trump also held a wide-ranging press conference a month into his administration where, for better or worse, he let loose. (Other parts of the executive branch have been much more worrisomely aloof. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has frozen out reporters almost entirely.)

There’s been fretting, most recently expressed in this New Yorker story about the briefings, that Spicer has shifted more questions toward right-wing organizations. It’s indeed dismaying that outlets controlled by Trump cronies like Rupert Murdoch and Christopher Ruddy have received favorable treatment. But while the New Yorker focused its ire on the execrable Gateway Pundit, that particular cretin hasn’t been given a single question. And the White House reporters from mainstream publications I’ve spoken to don’t seem to mind the overall mix of outlets Spicer’s calling on. On March 24, for instance, the Friday afternoon when the GOP health care bill disintegrated, you might have expected Spicer to cuddle up in the warm embrace of non-MSM outlets—yet his first five questions went to Reuters, Yahoo, the New York Times, the Associated Press, and Time.

Besides, with notable exceptions (including a couple of Skyped-in folks who’ve been nauseatingly chummy with Spicer), most questions from the right-leaning outlets have been legit. The Weekly Standard pressed Spicer on inauguration attendance claims; the Daily Caller and RealClearPolitics got tough on the bogus wiretapping accusations; even LifeZette asked a pointed immigration question in the first week. “It’s sometimes the questions from the right that Spicer has more trouble handling,” notes one correspondent, “just as the Obama administration sometimes had more trouble with the attacks coming from the left.”

Spicer has pulled occasional lame shenanigans, like excluding individual outlets from a gaggle or switching off briefing room cameras on a whim. These actions lie somewhere on the spectrum between encroaching autocracy and dick move. If anything, they’re efforts to distract and make the media a part of the story, as Trump did so effectively during his campaign and has continued to do with his “FAKE NEWS” tantrums. The press has an obligation to push back on behavior like this, and it’s done so, but we’re not in 1984 territory yet.

The real problem in the briefing room isn’t the kind of questions getting asked, who’s being allowed to ask them, or how they’re phrased. It’s the posturing of the press secretary and the brazenness of his lies. Consider that, during contentious moments in past administrations, press secretaries managed to remain collegial from the podium. Even deferential. Take a look at Dana Perino in 2007, defending Dick Cheney’s weird refusal to admit he was part of the executive branch. Perino is passive. She makes no attempt to control the room. Reporters bark out questions without raising their hands and (correctly) expect that she’ll respond. At one point, a reporter actually yells out “Yeah!” in solidarity with a colleague’s query. The balance of power lies in the seats, not at the lectern.

Or check out Jay Carney in 2013, putting a jolly face on the stumbling rollout of the Obamacare web site. He patiently back-and-forths with a single dogged reporter, ABC’s Jonathan Karl, dozens of times over a four-minute span. Carney’s attitude is waggish but jovial, never crossing into anger. Even defending President Obama’s “red line” statement about Syria, again in 2013, Carney is somber and respectful as he dodges roundhouse punches from Karl and from CBS’s Major Garrett. In all cases, the confidence and entitlement are on the side of the questioners.

Now watch Spicer’s press briefings over the administration’s first few months. You’ll notice the tonal difference is shocking. Spicer’s an alpha bully, often raising his voice in a threatening manner when a reporter touches a nerve. And the idea of a long, Carney-like give-and-take with Jonathan Karl is unimaginable. Whenever he’s under fire from a reporter who’s on a roll, Spicer simply cuts things off midquestion and calls on someone else. “He likes to Gatling-gun around the room,” says one White House correspondent. “He rarely lets a questioner build up rhetorical momentum.”

Spicer’s go-to move when he’s been cornered is to flip the script and recite a litany of media sins. He likes to couch these as “interesting” observations he’s made. Responding to a question, for example, about whether White House staff would know if Rep. Devin Nunes had checked onto White House grounds, Spicer wrapped up a long, nonresponsive media-crit digression by noting, “I think that that is interesting how no one seems to really cover the fact that a senior Obama administration with high-level clearances talked about the spreading of classified information for political purposes and no one seems to care.”

Whenever the corps does nail Spicer dead to rights, he has a fail-safe fallback: His words are ultimately meaningless. He’s an intermediary. He purports to represent the beliefs of a man whose first principles might flip upon viewing a Fox and Friends segment. Spicer can’t hope to capture the shifting, dispersing fog of Trump’s conceptual framework. At best, he can convey Trump’s id. And hope not to be contradicted later that evening by Trump’s tweets.

After Trump alleged that there were 3 to 5 million illegal votes cast in the general election and Spicer was confronted with the stark reality that there were not, he curled into a middle-man crouch: “The president does believe that,” Spicer said, distancing himself from Trump. “It’s a belief that he’s maintained for a while, a concern that he has about voter fraud.” A few weeks later, Jonathan Karl slyly countered this move by forcing Spicer to own Trump’s wiretapping accusations, asking if Spicer “personally believed” that Obama had tapped Trump Tower. Spicer again pulled the maneuver: “I get how that’s a cute question,” he said with a half-sneer, “but I’m not here to speak for myself. I’m here to speak for the president.”

Sometimes the intermediary acts more like a marionette. “You watch him get notes during the briefing,” says the person who worked for a past administration, referring to the Sharpie-scrawled slips that aides hand to Spicer at the lectern and that many theorize are coming straight from Trump, “and he reads them out loud immediately. We would never have done that! Read a statement from the podium that you’ve never seen before? No fucking way! You need to understand the limits of it, know exactly how to phrase it, sit down with the people involved. If you haven’t worked out the statement for yourself at some level, you’re just a mouthpiece, and that’s a bad place to be.”

The thing is, wanting to craft the statement in advance, wanting to take the time to pore over it and get it right would mean feeling it’s important for the White House to deliver some careful approximation of truth. What’s so disquieting about Sean Spicer is what’s so disquieting about President Trump: Neither cares about that.

* * *

Carlos Barria/Reuters

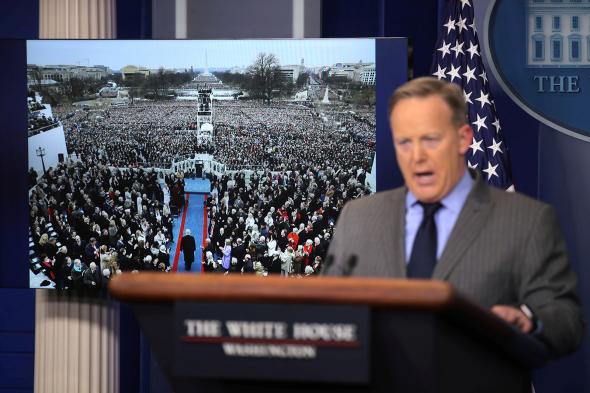

The complete disregard for truth—even the purposeful dissolution of it—was plain to see on the now-infamous opening Saturday of the administration, when Spicer summoned reporters to the White House so he could treat them to an impromptu address about the inauguration crowd size. Nothing formal. And no questions allowed. Spicer just wanted to lie to their faces for six minutes.

“People around D.C. didn’t know who that was. Where was the old Spicer?” asks one White House reporter. “He was not dealing with reality. You’re thinking, What did I just witness? There’s the seal behind the podium. Is this real?”

It sure was, and it hasn’t let up. Trump keeps belching out obvious untruths (millions of illegal voters; Obama wiretapped Trump Tower), and Spicer then defends them even when faced with clear contrary evidence.

It’s infuriating. It’s tiresome. And it means the press corps is forced to treat Spicer like a fibbing toddler. They repeat the same questions over and over, in carefully tailored variations, so as to eliminate the possibility of childish semantic outs.

Here are some, but by no means all, of the follow-up questions reporters asked about Trump’s wiretapping claims during a single briefing session on March 6, the Monday after Trump’s batshit tweets.

Q: So explain this to me, then. You’re talking about not using anonymous sources. What is, then, the sourcing for the president’s tweet on Saturday morning?

Q: And does he believe it’s a FISA warrant. Is it some other—of surveillance?

Q: So he doesn’t know?

Q: But what sources?

Q: Sean, does he not know whether—what kind of surveillance it was?

Q: But when he published his tweet did he know what kind of surveillance?

Q: A clarification here. You’re talking about the president wanting to go to Congress, specifically on the wiretapping question, but this is information that is held by the executive branch. So why would the president, if it’s information the executive branch has—?

Q: I’m just wondering when you said that it’s pretty clear that there was some sort of intelligence or wiretaps and that that’s why we need to move forward with an investigation, is that based on people speaking on the record or anonymous sources?

Q: Thanks. Sean, doubling back to something we talked about earlier. President Trump accused President Obama of criminal conduct. One, can you tell us what his source was for that accusation? Two, can you tell us, unequivocally, that he was basing that on more than a talk radio report and a Breitbart article about that talk radio report?

Q: So maybe it was just based on the talk radio report?

Q: This morning, Kellyanne Conway went on Fox News and she said, “He’s the president of the United States. He has information and intelligence that the rest of us do not.” So that seemed to be referring not to these news reports you’re talking about but to specific, tangible evidence. So what can you tell us about what that evidence is, where it came from? And then secondly, if he has this evidence, why is he asking Congress to investigate?

Q: But I was saying, was there an on—you were being asked was there an on-the-record comment in advance of the president’s tweets to which he was basing his information? Did he have anything better than anonymous sources?

Evidenced here is precisely the sort of tenacious burrowing that my lefty friends so often claim is absent from the briefings. It’s the surgical prosecution they always plead for, dreaming of an “OH SHIT” moment. Yet the cumulative force of this interrogation did not move Sean Spicer to drop to his knees, clasp his hands, and beg Jim Acosta for forgiveness. And having watched nearly every briefing Spicer’s done—either live or on my laptop—I’m here to tell you it’s utter fantasy to imagine anything would.

* * *

Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

“I think it’s good to occasionally poke the bear,” one correspondent tells me, when I ask him about confronting Spicer. “It might make Sean think about it driving home in his car when he’s alone. He’s not going to be the press secretary forever, but he’s going to have to live with what he’s said and how he’s behaved.”

But other correspondents find it less useful: “Sean has made a series of calculations that I don’t understand,” says one. “I guess existentially, you want someone not to be able to sleep at night if they’ve lied to you. But how he feels doesn’t affect how we do our jobs.”

So maybe ask yourself: What exactly do you want from the White House press corps?

Do you wish Major Garrett would rise to his feet and shriek, “Sean Spicer, you are a keg-shaped liar!”?

Perhaps you’d like Mara Liasson to clamber on her seat and yell, “Mr. Press Secretary, you’re a prole-gapping disgrace to the republic!”?

In other words, do you want conflict for conflict’s sake, producing heat but little light? Do you want the media to engage in a Trumpian manner, on Trump’s terms, granting you a dazzling show of resistance? That’d be entertaining, for sure. But I doubt it would provide what you’re really looking for, which is confession, self-flagellation, and remorse.

Instead, the press shows up each day to force the administration to present its case, which is often built on conspiracy theories and horseshit evasions. The reporters dutifully record the lies, as they always have, and keep pressing for the truth beneath, as they always have. That’s the simple value here. It’s the same old drudging, frustrating process, no more or less revealing than it’s been in the past—but more important now than ever. “We will continue to do our job and the truth will reveal itself,” promises one White House correspondent. “Lies collapse under their own weight. Liars eat themselves.”

At Spicer’s first officially scheduled briefing, Jonathan Karl (seated in that same front-row spot from which he’d once grilled Jay Carney) posed a sort of meta-query, in the wake of Spicer’s chilling opening gambit two days before. “Before I get to a policy question,” Karl began, “just a question about the nature of your job. Is it your intention to always tell the truth from that podium? And will you pledge never to knowingly say something that is not factual?”

Spicer at first claimed he’d be truthful. Then he danced around a bit. Eventually he turned the accusation back on the press. Karl got his answer.