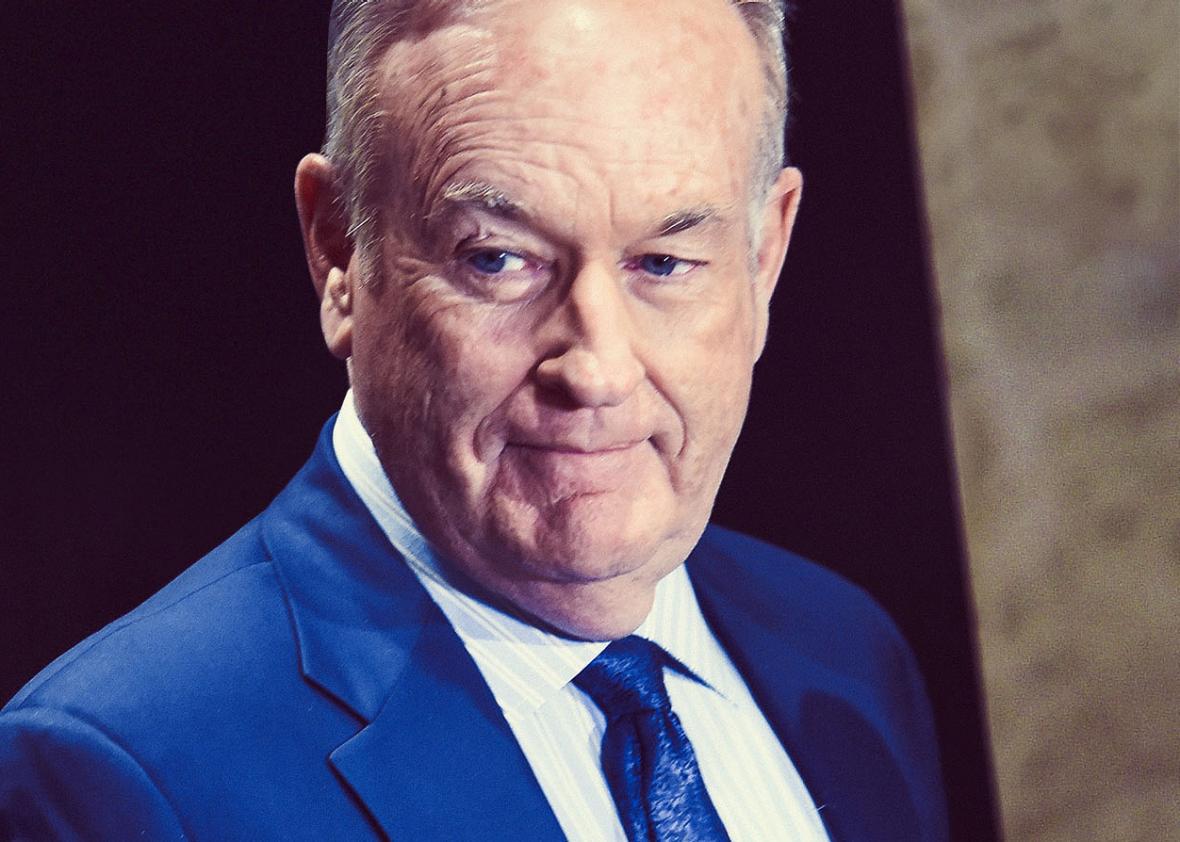

Bill O’Reilly and the Fox News Channel have negotiated an exit deal for the highest rated host in cable news. Thanks in part to vigorous reporting on numerous sexual-harassment allegations against him, a number of advertisers pulled spots from The O’Reilly Factor, which has now aired its final episode. As the most-watched host on the most successful cable channel of the past two decades, O’Reilly came to represent a style of in-your face conservatism that had previously been associated primarily with talk radio. O’Reilly’s uniquely aggressive personality and instinctual skills in front of the camera go a long way toward explaining his success. But he also tapped into the right-wing id in a way no one had before, captivating his viewers with his unbridled egotism and stoking their resentments. It was a playbook that won him a huge audience—and, to judge by Donald Trump’s eerily similar appeal to voters, a legacy that will outlast his grip on the 8 p.m. time slot.

When The O’Reilly Report began in 1996—the show didn’t become what O’Reilly referred to as “The Factor” until 1998—it was your typical anti-Clinton offering from Fox News, with many of the same preoccupations of other conservative programs in the second half of that decade. (White House scandals, mainly.) Over his first several years on the air, O’Reilly made an effort to appear reasonable. He declared that he was not a Republican, but an independent; he refused to support the death penalty; he talked about the value of environmental protection; he said that he understood both sides of the debate on issues such as gun control and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict; and he took immense pride—which manifested itself as smug self-satisfaction—in his supposedly nonpartisan, down-home common sense. This posture may have been dishonest—O’Reilly was a registered Republican who was happy to demagogue issues like gay rights when it suited him. But the gap between O’Reilly and robotic partisans such as Sean Hannity was noticeable, and the posture fit with the “fair and balanced” ethos that Fox News was then making an effort to pretend to uphold.

O’Reilly’s minor heresies during his first decade on the air were ultimately less indicative of the future direction of his show than the passions that always consumed him. These were not the same passions of the Club for Growth crowd. O’Reilly was naturally in favor of tax cuts and smaller government, and after 9/11 he became predictably jingoistic, offering full-throated support for the Iraq war and a tough line on terrorism. But even then it was clear that the traditional Republican platform never really motivated him. The idea of O’Reilly spending more than 30 seconds talking about supply-side economics was unfathomable; Limbaugh and Hannity would do so constantly. Instead, what motivated O’Reilly were two kinds of resentment.

The first was typical of the cultural conservatism of our age, and generally consisted of free-floating anger at any figure or institution that didn’t uphold what O’Reilly called “traditional values.” A college professor would call America a fascist country, or a retailer would announce that it would greet customers with “happy holidays” rather than “Merry Christmas.” O’Reilly would rant and rave; he would call for people to be fired; he would bemoan that America was becoming less religious and less white. (One of his many silly books was called Culture Warrior; the latest is Old School.) Sure, Limbaugh and Hannity would occasionally focus on culture instead of politics, but for O’Reilly, it was what fueled the show, and what really got him exercised. (Much was made of his Levittown upbringing and disdain for snobby elites.) Even better, he didn’t appear to be faking it in the way one often suspects of certain right-wing hosts. All of the details that have leaked out about O’Reilly—from the harassment claims to the violent way he behaved toward his ex-wife—strongly suggest that he was not playing a character when he fumed on the air.

But the aspect of The O’Reilly Factor that always shocked me was a different kind of resentment, which took the form of the anchor’s unrepentant solipsism. It’s simply impossible to overstate how much of each night’s show was consumed by O’Reilly’s own grievances. He skirmished with everyone from Matt Lauer to Rosie O’Donnell to Al Franken, and those fights would invariably become the topic of the day on his show. He spent countless hours talking about himself—usually as the victim of various conspiracies. (Frequently, George Soros was the conspiracy’s prime mover.) He would drone on about the New York Times and how it was out to make him look bad. It was endless, and it was exceptionally boring—to everyone except his legions of viewers and fans.

I never really had a theory for how this supposed man of the people got away with talking about nothing but himself. Then Donald Trump came along. Here was another rich guy who built a following speaking up for the working man. Like O’Reilly he seemed entirely driven by resentment: at President Obama, at the media, at the people who doubted him. And like O’Reilly, he spoke almost entirely of himself. His stump speeches were shocking, in part, because they were rarely about anything other than Donald Trump. When I would see him talk to a bunch of working-class voters in the Midwest and appeal to them by describing his own battles with CNN, I was surprised. But not as surprised as I would have been if I hadn’t been watching O’Reilly all these years.

I have no idea if Trump—a compulsive Fox News watcher—consciously modeled aspects of his personality (or at least the ones that are conscious constructions) on O’Reilly. (They were friendly with each other well before Trump began his run for the presidency.) But if we had been paying closer attention to just how O’Reilly managed to succeed, Trump’s rise would perhaps have been a bit less of a shock. Neither man’s appeal was primarily about something like “economic insecurity”; it was about group identity, and the cultural resentments that each man expertly cultivated. When your viewers (or voters) feel the same resentments, and come to view you as one of them, anything and everything becomes forgivable, and your trials and tribulations, however foreign, somehow become relatable.

Whatever Trump took from O’Reilly, it seems clear that the Donald’s unlikely political rise emboldened the Factor. In recent months, O’Reilly has become a conspicuously more Trumpist figure. The racism and misogyny have been dialed up; the hard edge on issues like immigration, on which he had once tried to equivocate, have been emphasized; and his partisanship is now so obvious as to be a punchline.

In 2016 and 2017, as both O’Reilly and Trump battled accusations of misconduct, it’s been hard not to see them as twinned: bigoted, sexist dinosaurs from the past. Each man went to extreme lengths to defend the other, and you sensed that this wasn’t only because they share the same audience but also because they have so much in common, that they really do see themselves in one another.

Which is why it was initially so exhilarating to hear that the O’Reilly era has ended, at least on Fox: Finally we are seeing the downfall of a true symbol of reaction and misogyny. But satisfaction these days has a tendency to give way to despair. An even larger symbol (and transmitter) of these ugly ideas is sitting in the White House. O’Reilly’s time has finally come, but the forces he helped unleash on American culture remain ascendant.