The American Health Care Act appears not long for this world. No one wants to vote for Trumpcare in its current form—not conservatives, not moderates, not anyone. Republicans might be complaining about the assumptions the Congressional Budget Office used to produce its atrocious score, released on Monday, and top leadership might be pretending like there’s nothing to see there. But rank-and-file do seem to recognize, as Arkansas Sen. Tom Cotton put it Tuesday morning, that the CBO score is “directionally correct.” More people will be uninsured; older, low-income people will be wholly priced out of the market; and premiums will still increase, albeit at a slightly slower pace on average.

Trade-offs in health care legislation are to be expected. But for what are they trading here? Tax cuts for the wealthy don’t appear to be enough this time around. This is a bad bill with no clear benefits for members to sell to their constituents. Members know that, and that’s why it has to change.

But how? GOP leadership is going to have to figure that out and soon.

Senate Republicans on Tuesday continued to take issue with the CBO’s calculation that 24 million people will lose insurance by 2026, saying it applies too much weight to the effect of Obamacare’s individual mandate. There’s a case for that—in the short term. But there two far more glaring and less dismissible problems in the eyes of would-be backers: The bill appears to go out of its way to destroy older, low-income people for sport, and it doesn’t lower premiums.

The first problem likely means the bill’s refundable tax credits are going to have to be altered once again—and ironically, altered in a way that brings them closer still to those offered under the Affordable Care Act. (Some conservatives have already panned the bill as “Obamacare Lite,” so this might not play so well with them.)

The leaked AHCA draft dated Feb. 10 called for purely age-based tax credits rather than the income-based credits Obamacare offers. Rank-and-file members soon began to notice that this meant millionaires were getting the same tax credits as low- and middle-income people. The current version was altered to means-test from the top, gradually phasing out the tax credit after a certain income. There is, however, no means-testing added from the bottom to help lower-income people. And so yesterday’s CBO score showed that, say, a 64-year-old making $68,200 would receive the same tax credit as a 64-year-old making $26,500, requiring those poorer 64-year-olds to pay more than half of their income in premiums should they want insurance.

That was bad, and senators know it.

“Older, low-income people are the most in jeopardy in the plan,” Missouri Sen. Roy Blunt, a member of the Senate leadership, said Tuesday. “We need to look at the least well-served in a new marketplace: is there a way to shift some of the opportunity of systems towards them? I think we can do that.”

South Dakota Sen. John Thune, a fellow leadership member, said that “there are things we can do to tailor the tax credit in a way that makes it more attractive to people, and more helpful to people, on the lower-end.” And after leaving a caucus luncheon with Vice President Mike Pence, North Dakota Sen. John Hoeven confirmed that re-jiggering the tax credit more favorably towards older, low-income people was one of top priorities discussed.

Hoeven also alluded to another discussion underway on how to bring down those premiums: trying to squeeze more market deregulation into the reconciliation bill. He said that leaders were talking to the Senate parliamentarian “to see what else” they could do.

Regulatory changes, like eliminating essential benefits requirements for qualifying health plans or allowing insurers to sell across state lines, could have the sort of dramatic effect on lowering average premiums that is ostensibly the entire goal of the Republican health reform effort. (You’d also get what you pay for with cheap, low-value plans, but that’s a discussion for another piece.) Leadership has said that Senate rules don’t allow for these changes to pass under reconciliation. But without them in the bill, there’s no big-ticket benefit—like significant average premium reductions—to help members sell this act as worth the paper it’s written on.

“The most troubling aspect of the CBO report,” Sen. Ted Cruz said Tuesday, “was its projection that under the House bill premiums would continue to rise next year and the year thereafter. That is unacceptable.”

“The only way to drive down premiums is to repeal the crushing insurance mandates that are driving premiums through the roof,” he continued, “and to do so immediately.” He said these needed to be done “now.”

I asked Cruz if leaders were more open to pressing Senate rules now. He said that it was a “subject of active negotiation.”

As I wrote on Monday, the House bill is already incoherent on Senate rules: It includes some items that appear more like regulatory than direct budget reforms into the bill while not including other, similar measures.

Speaking on Hugh Hewitt’s radio show on Tuesday, Cotton appeared to agree.

“I simply don’t understand why the House bill has tried to repeal—it tries to repeal some of the regulations of Obamacare, it modifies some of the other regulations, although it doesn’t repeal them, and then it leaves others in place on the grounds that they can’t be touched through this process,” Cotton said. “I don’t see why that is a consistent view.” Cotton thinks that members should “take a bolder stance about the number of those regulations that can be included inside this process, because those regulations clearly have a huge budgetary impact.”

Politico reported on Monday night that the White House was discussing this very possibility with House conservatives.

It would seem that at least trying to include all of these items, and thus giving members more high-priority reform items in the bill, would be worth a shot. If the parliamentarian advises they be stripped out, then they strip them out and are back where they started. Or they overrule the parliamentarian.

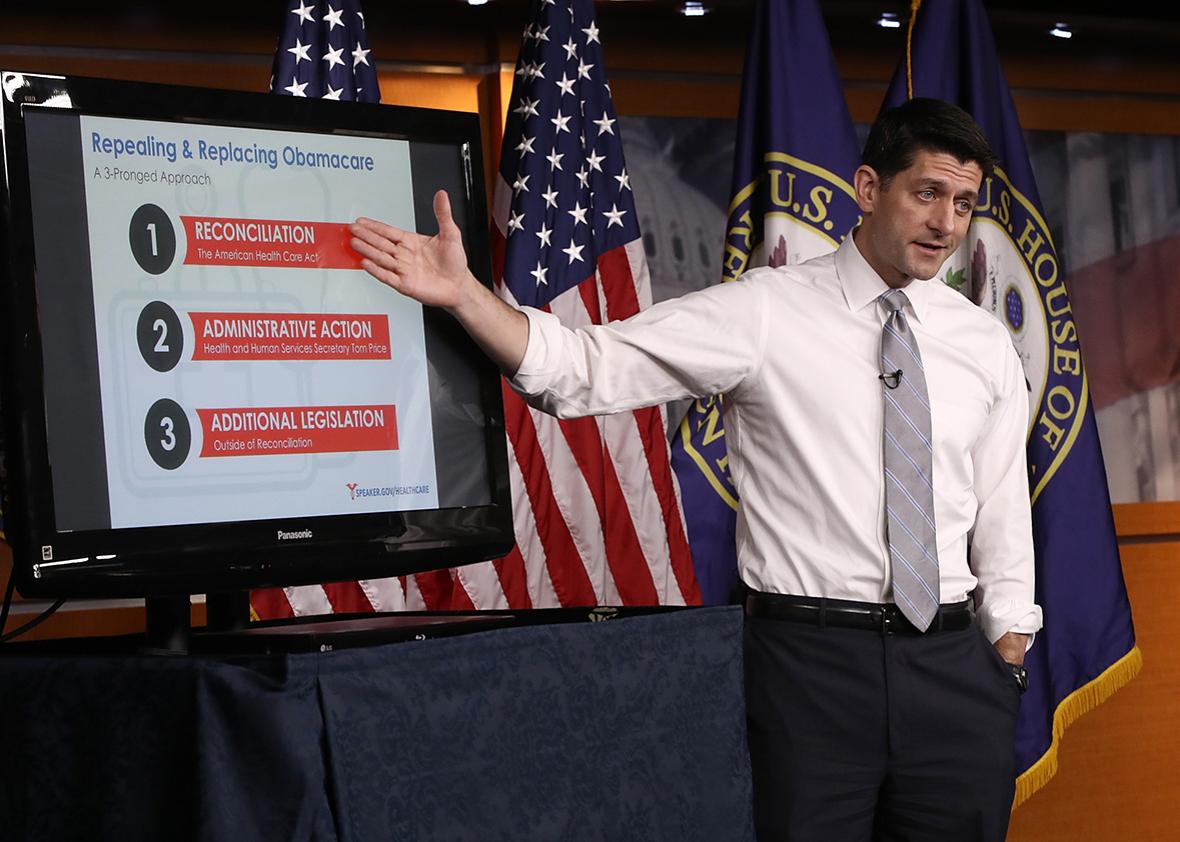

Parliamentary hardball would seem especially vital given the flimsiness of the talking point leaders are currently using to explain why they can’t fully reform the health care system in this bill: the three-step plan. “There is no three-step plan,” Cotton said, giving a succinct explanation of why that’s just “spin.”

Step one is a bill that can pass with 51 votes in the Senate. That’s what we’re working on right now. Step two, as-yet unwritten regulations by Tom Price, which is going to be subject to court challenge, and therefore, perhaps the whims of the most liberal judge[s] in America. But step three, some mythical legislation in the future that is going to garner Democratic support and help us get over 60 votes in the Senate. If we had those Democratic votes, we wouldn’t need three steps. We would just be doing that right now on this legislation altogether. That’s why it’s so important that we get this legislation right, because there is no step three. And step two is not completely under our control.

Passing this bill as-is would screw congressional Republicans almost as much as it would screw the older people who voted them into office. A tweak here or there won’t get the party the votes it needs. Leaders will have to try a different approach, perhaps one that allows them to meet any of their stated health care goals.