The American Health Care Act is in trouble, not least because the Congressional Budget Office issued a devastating report that projects that 24 million fewer people would have health insurance by 2026 if Ryancare is enacted versus if Obamacare remains intact. Because I’m not a fan of Ryancare, I suppose I should be glad the CBO likely helped drive a stake through its heart. But the CBO’s scorekeeping is a double-edged sword. Yes, it’s helpful to know how much new legislation might cost over time. It would be even more helpful, though, to give more thought to how new legislation might work over time.

When we debate the virtues of Obamacare, we tend to focus on the many ways the legislation increased the number of Americans with subsidized medical insurance. That’s fair enough, as the chief motivation behind the law was to reduce the number of uninsured people in the United States. To achieve that goal, Obamacare had to make it through Congress. The Democratic policymakers who designed the legislation had to overcome both Republican opposition but also skepticism from centrist Democrats who were wary of creating a new, budget-busting entitlement.

One way or another, advocates of coverage expansion felt they needed to prevent “sticker shock”—the political fear that comes when a new spending program costs a scarily large amount of money. And so, as Ezra Klein and Sarah Kliff of Vox remind us, Democrats imposed a number of artificial constraints on Obamacare, the most important of which was that they needed the CBO to report the new law would not increase the budget deficit over its first 10 years. Indeed, if Democrats could claim that Obamacare meaningfully reduced the budget deficit, they’d have a powerful argument to make to the wavering centrists in their own party, and they’d have a shield against Republican charges of fiscal recklessness.

In the end, Democrats succeeded in getting a favorable CBO score for their coverage expansion bill. One reason why is that they included a number of new taxes to help pay for it, most of which Republicans now intend to repeal. But that wasn’t the only thing Democrats did. Consider the Community Living Assistance Services and Supports Act, an obscure program that was originally part of Obamacare before getting abandoned in the fall of 2011, not long after it was signed into law. In When Bad Policy Makes Good Politics, University of Montana political scientist Robert P. Saldin makes the case that CLASS was a crucial part of why Obamacare made it through Congress despite the fact that just about everyone knew it was completely unworkable and destined to be abandoned.

The idea behind CLASS was a noble one. A growing number of older Americans need long-term care, but only a small handful have the resources to pay for it. CLASS aimed to tackle that problem by creating a new long-term care insurance program that would be voluntary, charge extremely low monthly premiums, and be open to just about any employed person. After paying into the system for five years, those who signed up would be eligible for benefits. The problem with CLASS, as Saldin carefully explains, is that “far too few people would be paying into the program to cover the costs of those receiving benefits.”

So, why was CLASS folded into Obamacare? Because it helped juice the Affordable Care Act’s CBO score. Since those who signed up for CLASS coverage wouldn’t be eligible for benefits for five years, that meant the program would generate nothing but revenue for half of the CBO’s 10-year budget window. To be clear, the CBO was entirely aware of what was going on, and the agency explicitly called out the fact that the CLASS program would prove extremely costly in the long run in its analysis. That caveat didn’t really count for much politically, however. All that mattered was that the all-wise, all-knowing CBO had declared that CLASS was deficit-improving. As Saldin writes, “the irresistible appeal of CLASS wasn’t because it was seen as an important step in addressing America’s long-term care challenge; rather, it was because of the money it brought to the Affordable Care Act.” When CLASS was eventually abandoned, hardly anyone batted an eyelash. But without CLASS, the case for Obamacare would have been harder to make.

Obamacare’s champions were hardly alone in working the CBO process to make expensive policies look cheap. Saldin cites the Bush tax cuts as a sterling example of how this particular game is played. By making reductions in tax rates “temporary,” the George W. Bush administration and its allies in Congress made the resulting drop in revenue look much smaller than if those tax cuts had been deemed permanent. Of course, Republicans who backed the Bush tax cuts had no intention of allowing them to lapse. Medicare Part D, also championed by the Bush White House, is another example. Like in the case of CLASS, the program’s costs were expected to balloon after the 10-year budget window had passed.

There are lessons in all of this for policymakers whether they’re on the left or the right. It’s a truism in life that when the outcome you want depends on acing a test, you’re going to do whatever you can to ace that test. Democrats and Republicans both see a CBO evaluation as a test they need to ace, but it’s too often seen as a substitute for learning the material—or in this case, tackling a policy challenge.

With Obamacare, Democrats wanted to expand coverage in a politically sustainable way. By devoting so much effort to getting a good CBO score, they might have made that goal more difficult to achieve. For example, Klein and Kliff note that many Democrats now believe that Obamacare would have been on much firmer ground had it devoted more money to premium subsidies at the expense of a “worse” CBO score. Nevertheless, Democrats did succeed in passing Obamacare, and Republicans are discovering how difficult it will be to repeal and replace it. If Obamacare remains the law of the land, future Democrats will have an opportunity to build on it.

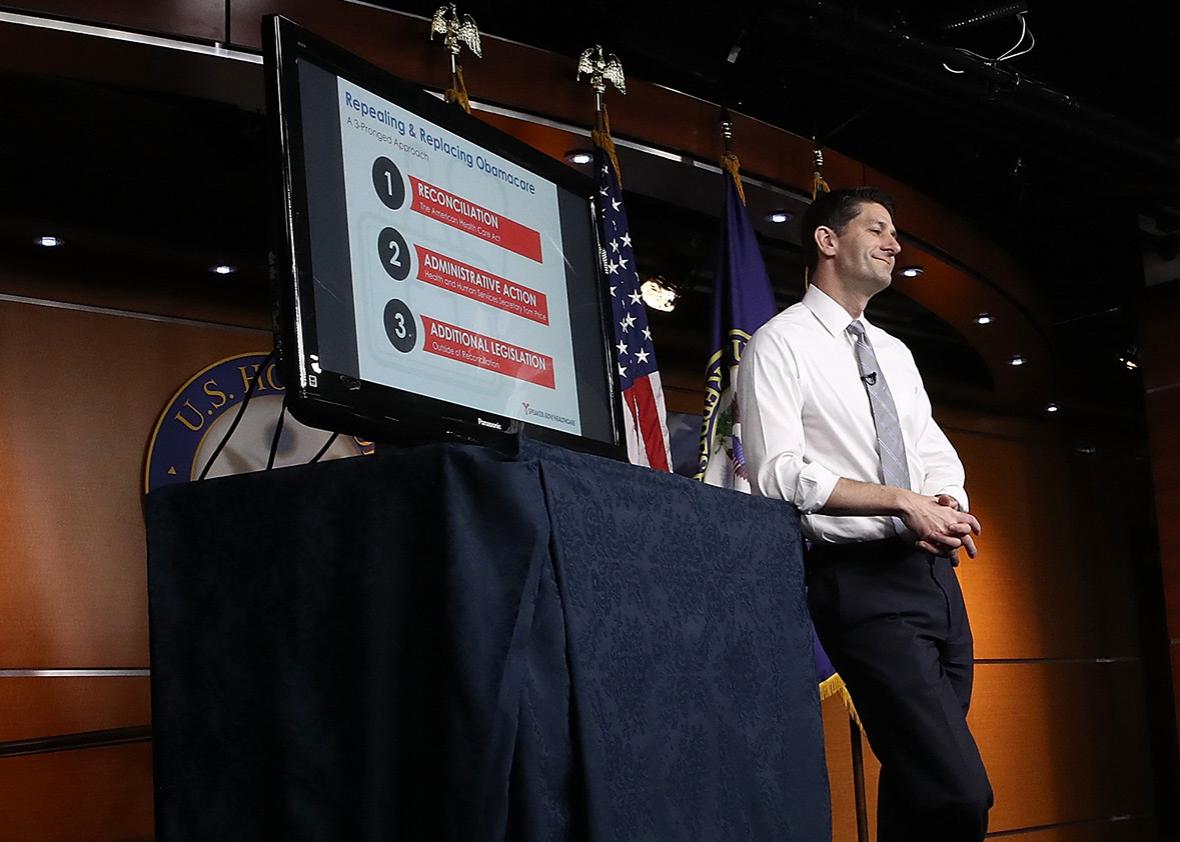

Republicans face a different challenge. They were inevitably going to stand accused of caring too little about the number of people who’d be insured by their Obamacare replacement, but they failed to tweak the legislation with that critique in mind. The result is that the AHCA is unlikely to be signed into law, and Republicans will have nothing to build on.

If this all sounds very cynical, well, that’s because it is. The fault here lies not with the CBO, which does the best it can with its narrowly circumscribed role. It’s with all of us, on the left and right, who fixate on making the numbers look good and pay little heed to how a policy is actually going to work.