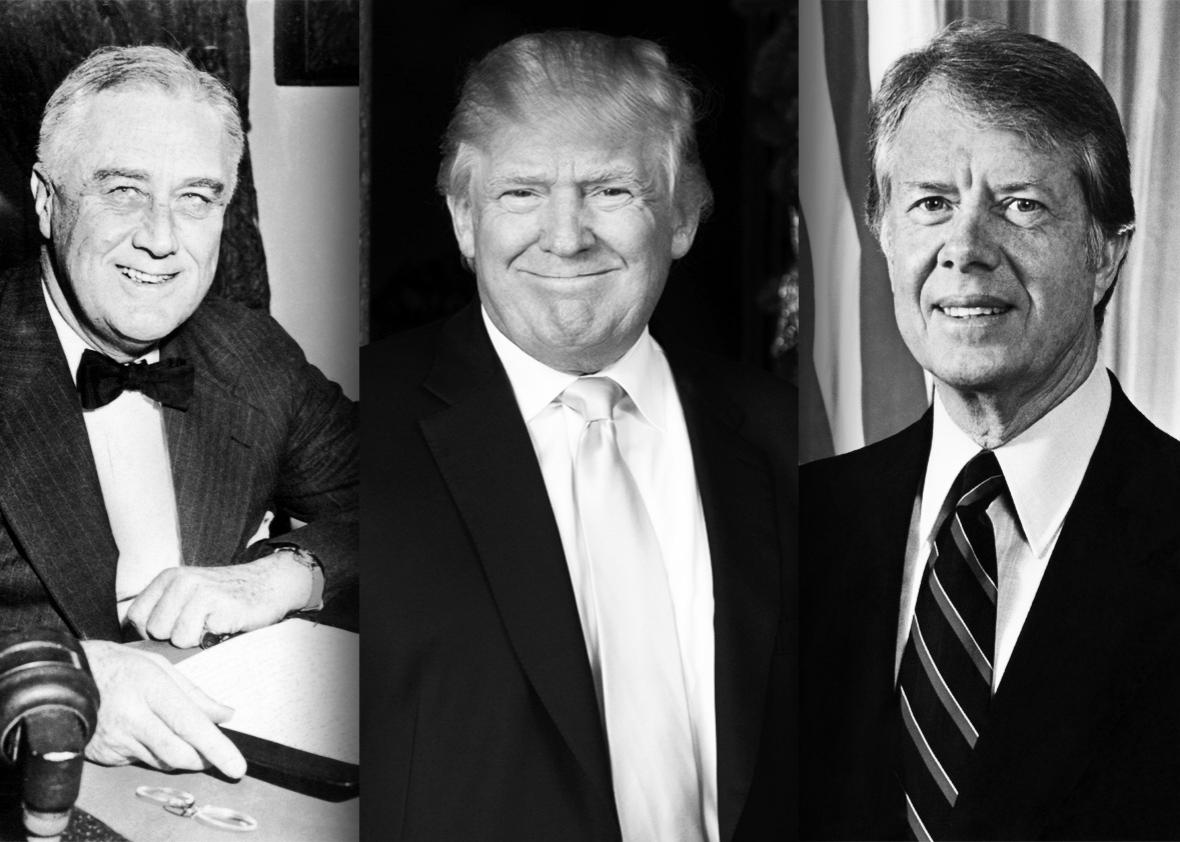

Is Donald Trump going to be a transformative president, in the mold of Franklin Delano Roosevelt or Ronald Reagan? Or will he be more like Herbert Hoover or Jimmy Carter, a president whose failures pave the way for a transformative successor?

A number of thinkers on the left, including Jack Balkin of Yale Law School, have been asking that question since Trump’s victory in November, drawing on political scientist Stephen Skowronek’s influential “political time” thesis. The basic idea is that there is a recurring pattern in presidential history, which starts when a transformative presidency creates a new political order out of the ashes of an older one (think the transition from Hoover to FDR). This transformative president is typically followed by a loyal disciple (Harry Truman, for example), and then by a president of the opposite party who has little choice but to operate within the existing political order (Dwight Eisenhower). As long as a given political order persists, power rotates between presidents who are devoted to the reigning political orthodoxy (John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson) and those who resist that orthodoxy but can’t quite dislodge it (Richard Nixon). Skowronek’s cycle ends with a president who seeks to uphold a political order that is on the verge of collapse due to internal conflicts and contradictions that grow ever more difficult to reconcile. In the cycle that began with FDR, the unlucky president left holding the bag was Carter. The Georgia governor tried to keep together a New Deal coalition that united Northern liberals and Southern conservatives via his idiosyncratic mishmash of Christian moralism and technocratic wonkery, but he instead triggered intense intra-party opposition, up to and including a formidable primary challenge from Ted Kennedy. These “disjunctive” presidencies inevitably fail and pave the way for the next transformative presidency.

In an interview with Richard Kreitner in the Nation, Skowronek said he believes we are coming to the end of one of his cycles, a conservative political order that began with Ronald Reagan, continued with George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush, and was resisted by Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. That leaves Trump as another Carter, who will try and fail to paper over the deep divisions plaguing Republicans. The Trump-as-Carter thesis is obviously comforting to liberals, as a disjunctive Republican presidency presumably means a transformative Democratic one is soon to come. That’s not the only possibility, however. There is a chance—a remote one, to be sure—that Donald Trump will remake American politics.

Whether or not Trump becomes a transformative president, he clearly ran a transformative campaign. Trump’s great political insight was that a vast chasm separated the existing Republican coalition and the Republican coalition that existed in the minds of party activists, donors, and elected officials. Essentially, elite Republicans saw their party through the lens of makers and takers. Republicans build businesses, pay taxes, and provide for their families. Democrats, in the view of GOP elites, are always on the lookout for free stuff while Republicans are the “leave-us-alone” coalition, a group of Americans that want the government to get out of their way.

It should go without saying that this characterization of the GOP is misleading in the extreme. Many reliable Republican voters are older Americans who rely heavily on Social Security and Medicare, and who haven’t paid federal income taxes in years. Others are working- and middle-class people living in small towns and exurbs, who benefit directly or indirectly from safety-net programs. When Mitt Romney spoke dismissively about “the 47 percent,” at least some of these voters got the impression he was talking about them. This is the kind of intra-party tension Skowronek identifies, and that brings political regimes to an end.

At the height of the Reagan era, when America’s electorate was younger, and when the unionized working class was still more or less intact, the class-based theory of the Republican coalition made a good deal of sense. By the 2010s, however, it should have been clear that it was losing its salience. In 2012, the Democratic presidential candidate won a larger share of the vote among households earning $250,000 or more, the first time that had happened since 1964, when Barry Goldwater’s loose talk about tactical nukes terrified ritzy Republicans into voting for Johnson. Democrats won this rarefied constituency in 2016 as well. This is not to suggest that Republicans and Democrats suddenly switched places. Rather, over the course of the Obama years, the Democrats evolved into a barbell party, representing affluent educated voters at the top of the income distribution and nonwhite working-class voters at the bottom. Republicans evolved into a party of white middle- and working-class voters, plus tax-averse ultra-wealthy types who set the party’s agenda without providing much electoral punch. While rich Republicans remained wedded to the rhetoric of makers and takers, their party had become a cross-class coalition that included makers and takers alike.

Enter Trump, who rejected the maker vs. taker concept and replaced it with one pitting nationalists against globalists. This new distinction fit the sensibilities of the new GOP electorate. If makers vs. takers is about the rich vs. the poor, nationalists vs. globalists is about winners vs. losers. On one side you have the regions that have profited most from global economic integration, and on the other you have those that have been hardest hit. Regardless of class status, people living in regions devastated by import competition might be skeptical about a “globalist cabal.” People who felt as though they were better off than their parents—middle-class adults raised by immigrant strivers, upwardly mobile black Americans facing less intense discrimination than their parents did, high-achieving children of the meritocracy—tended to be less receptive to Trump’s message than those who felt worse off. And as sociologist Andrew Cherlin argued in a New York Times op-ed published in August, it wasn’t just low-income whites in the Rust Belt who feared middle-class stability was slipping away from them. Trump also appealed to better-off older whites alarmed by the (seemingly) diminished prospects of their children and grandchildren. Something similar could be said of at least some of the black American voters who voted for Obama but who chose not to vote for Hillary Clinton.

Trump’s transformative campaign hardly ended in a landslide. As much as Trump and his devotees hate to hear it, he lost to Hillary Clinton by a wide margin in the popular vote. But by moving beyond makers and takers, Trump introduced the possibility of a new cross-class politics, and of a transformational presidency.

A Trumpist, nationalist party could embrace the safety net, and perhaps even selectively expand it. If globalism has exacerbated domestic inequality, nationalism could endeavor to ameliorate it, by tightening labor markets, encouraging productive business investment in the domestic economy, and creating pathways to upward mobility that don’t necessarily require a college education. One can imagine a party built around the white middle class growing more ethnically expansive, by bringing growing numbers of native-born Hispanics into the fold, especially those living outside ethnic enclaves and in fast-growing, low-cost suburbs. FDR pulled off a similarly ambitious feat in his era. Might Trump pull off the same feat in ours?

Probably not. Thus far, Trump has done nothing more than introduce the possibility of a new nationalist politics. Even if the president-elect himself were to wholeheartedly embrace the idea of a unifying, wealth-creating, inequality-reducing nationalism, it’s not clear it would matter all that much. To implement a transformative agenda, Trump would need true believers to staff his administration and to do battle with his intra-party rivals. There are a number of intellectuals who could, in theory, lead the way. The trouble is that it’s hard to imagine any of them allying themselves with Trump. Robert Atkinson of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation has made a compelling case for a national productivity strategy that avoids crude protectionism. Michael Lind of New America has been thinking about how to better the lives of working-class families in the age of globalization for years. And then there are the critics of unchecked globalization on the center-left, such as economists Dani Rodrik and Michael Spence, who acknowledge that there is a place for a responsible economic nationalism, yet who see Trump’s chauvinism as disqualifyingly retrograde. And it’s hard to blame them.

Suffice it to say, none of these thinkers enjoy wide influence among Republicans in Congress, let alone Trump’s inner circle. So far, Trump is staffing his administration with pretty much the same Reaganites who would have served under Jeb Bush, his favorite globalist foil. You could say that Trump won a premature political victory. Republican voters were ready for a cross-class, nationalist appeal, but today’s elite Republicans, who cut their teeth in the makers and takers era, appear to be completely uninterested in giving it to them. And the president-elect himself hasn’t been acting particularly transformative. Trump’s personnel decisions in the past two months suggest he intends to do nothing more than layer a candy-covered nationalist shell over the chocolate-covered peanut that is Reaganism. Add a few well-timed, angry tweets and a few bread-and-circus-like gestures, like the Carrier deal, and you’re good to go.

We may very well have a transformative nationalist president in our lifetime, who will draw on ideas from the right and the left. It’s just not going to be Donald Trump.