On its face, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act was a mere update of the 1793 fugitive slave law, written to enforce the Fugitive Slave Clause in the Constitution. And defenders of the act, a key part of the Compromise of 1850, framed it as a constitutional obligation. “Every member of every northern legislature is bound, by oath, like every other officer in the country, to support the Constitution of the United States; and the article of the Constitution, which says to these states, they shall deliver up fugitives from service, is as binding in honor and conscience as any other article,” argued Massachusetts Sen. Daniel Webster in his epic “Seventh of March” speech urging the chamber to adopt the compromise.*

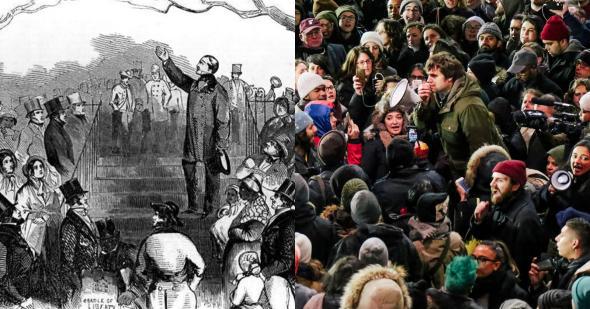

Webster wasn’t wrong—if the Constitution meant anything, it meant Northern states had to comply with the Fugitive Slave Clause. And if they wouldn’t, then Congress would make them. But he badly misjudged the politics of a strengthened Fugitive Slave Act. The new law deputized their officials as slave-catchers and punished resisters with stiff fines and jail time, and Northerners reacted with fury. Blacks and their white allies did everything in their power to nullify the law, from legal challenges, protests, and organized flight to Canada to outright armed resistance. “We must trample this law under our feet,” declared abolitionist Wendell Phillips.

The slave South wanted this law. But what it didn’t understand—what it didn’t anticipate—is that it would galvanize and energize opposition to slavery. It would turn people who were uncomfortable with slavery into outright opponents and turn mere opponents into radical abolitionists. The South and its defenders won the fight to make Washington a tool of slave power. In the process, however, it hardened its adversaries and grew their numbers.

President Trump’s travel and refugee ban—effectively, his long-promised “Muslim ban”—isn’t the exact moral equivalent of the Fugitive Slave Act, though future Americans may treat the administration’s order with the same contempt and bewilderment as present-day Americans do that law. But politically, it has had a similar effect. The cruelty and capriciousness of the ban, evidenced by stories of detained children, separated families, and frightened refugees, has supercharged liberal opposition to the Trump administration. Its arbitrariness—the sloppy, haphazard way in which it was drafted and implemented—has alarmed moderate observers. And its clear roots in anti-Islamic bigotry, by way of White House figures Stephen Bannon and Stephen Miller, led the acting attorney general (since fired) to announce her intent not to defend the order in court.

In the aftermath of the election, Donald Trump faced a fragmented field of opponents: cautious Democrats, frustrated activists, and a divided grassroots still struggling to build a common front. Now, he stands opposite an increasingly unified opposition, energized by weekly protests that draw tens of thousands of people—if not far more—nationwide. Trump may have delivered on his promise to keep refugees and Muslim immigrants off American soil. But now he must contend with furious opponents who will not bend or compromise.

The determined anger of grassroots opposition is evident from the behavior of Democratic officeholders, who witnessed nationwide protest against the order and acted accordingly. Over the weekend, this meant joining protests, giving statements of solidarity, working on behalf of stranded refugees and green card holders, and announcing plans to challenge the order. “We are a state that is opening and welcoming to everyone. I’m very concerned about the ramifications of this new executive order,” said Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, who instructed state Attorney General Mark Herring to look into “all legal remedies” to assist those affected in Virginia airports. Other Democratic governors, both moderate and liberal, took similar steps.

Likewise, after flirting with some cooperation with the Trump administration, Senate and congressional Democrats have adopted a stance reminiscent of Tea Party legislators. But while the latter opposed ordinary and routine parts of government, the former stand against questionable and broadly unqualified Cabinet nominees. On Tuesday, for example, Democrats on the Senate Finance Committee skipped key votes in order to stall confirmation of President Trump’s nominees for the Department of Treasury and the Department of Health and Human Services. Their reasons? Evidence that neither nominee had been honest with the committee, misleading members on allegations of insider trading and foreclosure practices. Democrats on the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee voted unanimously against Trump’s controversial nominee for secretary of education. Betsy DeVos is a flashpoint for opposition to Trump, such that even red-state Democrats are at risk of backlash if they support her confirmation. It is why North Dakota Sen. Heidi Heitkamp has announced her opposition, despite representing a state that voted for Trump over Hillary Clinton by a rough 2-to-1 margin.

Democrats are taking a similarly strident approach to Alabama Sen. Jeff Sessions, the president’s nominee for attorney general. Sessions has a long history of opposition to expansive civil rights laws, and recent reporting suggests he was a driving mind behind Trump’s immigration order. Indeed, Sessions is notable for highly restrictionist views that include praise for the 1924 immigration law, known as the Johnson-Reed Act, whose chief author, notes the Atlantic’s Adam Serwer, declared it was intended to end “indiscriminate acceptance of all races” by excluding Southern and Eastern Europeans, Africans, and Middle Easterners and barring all Asian immigration.

If there is an unanswered question in all of this activity, it is the position of House and Senate Republicans. Will they back the president, even as he undermines their standing and gives lie to election-year statements of principle? His popularity with their voters suggests a solid yes, as does Paul Ryan’s stalwart support of Trump, all in service of reduced taxes and sharp cuts to the social safety net. But while this solidarity worked before—it helped Republicans win full control of government—it may also leave them vulnerable if the rising tide against Trump becomes a wave.

None of this was inevitable. As recently as last week, key Democrats were strategizing the ways in which they would oppose Trump—or work with him to preserve political capital. The refugee ban has changed the board and the stakes. Now, working with Trump means collaborating with racist and exclusionary policy. It means bolstering a White House that has shown its contempt for law and procedure. And it means standing against a firestorm of anti-Trump anger among the people who send them to office.

“We went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs and waked up stark mad Abolitionists,” said New England philanthropist Amos Lawrence about the Boston slave riot of 1854, part of the yearslong wave of resistance to the Fugitive Slave Act. Between the mass protests, the fortification of “sanctuary cities,” and the all-out opposition of sympathetic lawmakers and lawyers, Trump’s refugee ban has had a similar effect on the Democratic electorate and its representatives. It is impossible to say, at this stage, how this fight will resolve itself. But we can say, at least, that we have entered a new, heated, and ultrapolarized era of politics, with deeply uncertain consequences for our government and our way of life.

*Correction, Feb. 1, 2017: This article originally misquoted Daniel Webster as saying “bind” instead of “binding” in his speech. (Return.)