A decade ago, Barack Obama was already contemplating his presidential legacy. I know because I talked to him about it in 2006, during a long interview for a now-defunct men’s magazine. In a reflective mood after finishing his second book, his suit coat off and necktie loosened, the 44-year-old freshman senator opened up about his political ambition.

“My attitude about something like the presidency is that you don’t want to just be the president,” he told me. “You want to change the country. You want to make a unique contribution. You want to be a great president.”

Obama described visiting the Washington Hilton and walking down a long corridor decorated with pictures of all America’s presidents. “You go through, and you think, who are these guys? There are, what, maybe 10 presidents in our history out of 40-something who you can truly say led the country? And then there are 30 who just kind of did their best. And so, I guess my point is, just being the president is not a good way of thinking about it.”

In his final days in office, I’ve been remembering the bar Obama set for himself that summer afternoon and wondering whether he feels that he cleared it. Will Obama be remembered as a top-10 president, one who changed the country? Or as one of the perhaps admirable but not-quite-transformational others?

During his race against Hillary Clinton in 2008, Obama articulated the same distinction in a way certain to annoy her and her husband by saying that “Ronald Reagan changed the trajectory of America in a way that, you know, Richard Nixon did not and in a way that Bill Clinton did not.” Obama aspired to be a kind of liberal Reagan who would not just change policy but embody the emergence of a diverse and progressive society.

Jonathan Chait’s provocative new book Audacity, hastily updated for Donald Trump’s unforeseen victory, makes the case that Obama’s substantive accomplishments are both momentous and likely to survive the authoritarian circus now arrived in town. Chait points to the president’s handling of the 2008 financial crisis, the passage of the Affordable Care Act, and the Paris Accord on greenhouse gas reduction, as well as less heralded changes around education, financial regulation, and economic distribution.

Chait’s case about the significance of Obama’s achievements is more convincing than his prediction about their durability. After votes in the House and Senate last week, Obamacare appears to be headed for straight-up repeal rather than face-saving modification. During the campaign, Obama said that if Trump were to be elected, eight years of accomplishment would go out the window. Afterward, Obama put it rather differently, telling David Remnick of the New Yorker that he had done “seventy or seventy-five per cent” of what he intended. “Maybe fifteen per cent of that gets rolled back, twenty per cent, but there’s still a lot of stuff that sticks.”

Alas, the earlier warning looks more accurate. But whether universal health insurance survives in some form, the larger question is the one Obama pointed to in his comments contrasting Reagan with Clinton. “Reagan put us on a fundamentally different path because the country was ready for it,” he said. To count as transformative, a president needs to synthesize the moment and mood of the country. Where Reagan channeled disenchantment with overweening government, Obama symbolized America’s transformation into a multiracial country.

That demographic change is inevitable, but Obama was a precocious avatar. America remains 62 percent white, according to the Census Bureau. Not until mid-century will minorities become the majority. As Chait persuasively argues, the headwinds Obama faced were mostly racial blowback. In many cases, Republican politicians and white voters abandoned policies they had long supported once they were endorsed by a black president.

Given the racially tinged opposition he faced, it’s hard to make the case that Obama could have accomplished a great deal more either by being tougher or more gentle. Yet for someone who saw himself as a political bridge, the inability to produce any durable consensus must count as a tremendous disappointment. His faith in transcending partisanship, in the face of all evidence, stands as both inspirational and somewhat naïve. Obama called his pre-presidential book The Audacity of Hope. His post-presidential might be titled The Triumph of Hope Over Experience.

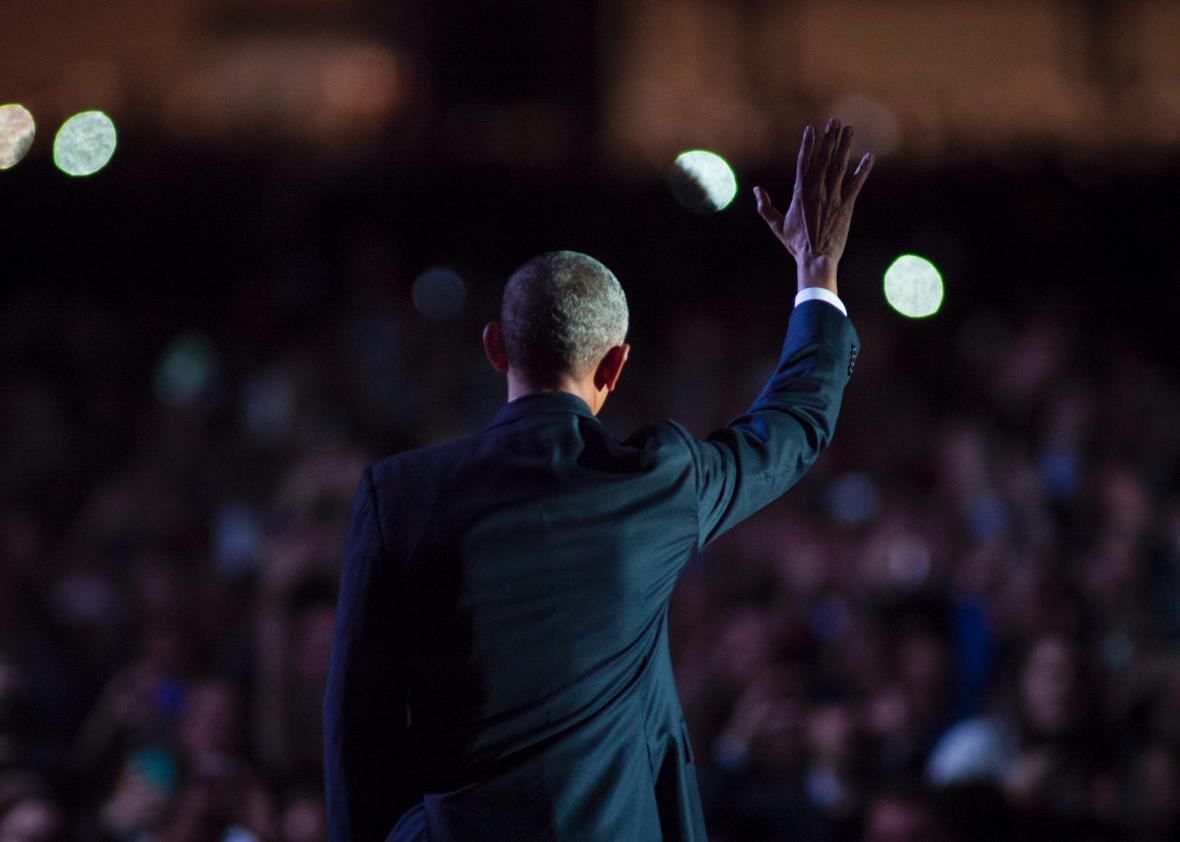

Ten years ago, Obama told me that establishing universal health care should be his party’s highest priority and that he worried about the lack of economic opportunity driving racial polarization. Listening to the powerful farewell address he delivered in Chicago last week, I was struck the remarkable consistency of his views and his approach. Despite the ways in which his worst fears have been borne out, he has remained rock steady in his calm application of reason, his respect for opponents who haven’t much respected him, and his methodical pursuit of common ground. Obama’s absence of bitterness is remarkable. He leaves a legacy of integrity, eloquence, and patient commitment in this dark hour of American politics.

___

A slightly different version of this piece appears in the Financial Times.