In the 1990s, Kellyanne Conway counseled corporations on what women want to buy and how to sell it to them. Among her clients was Vaseline, makers of the Kellyanne Conway of products. Petroleum jelly adds shine to lips and soothes delicate skin. It is glossy, softening, and relaxing. It exists to reduce friction, to make rough things easy and pleasant, to glamorize surfaces. It is also very, very slippery.

Cartoons often depict the highest-ranking woman in the White House as a lion tamer, the only soul capable of controlling a beast who would otherwise destroy us all. Saturday Night Live evinces more sympathy: Kate McKinnon plays Kellyanne as a hapless careerist in the thrall of forces greater than herself, swept into a position she doesn’t want and wracked with guilt at the damage she’s unleashed. On her day off, she dances down a staircase to make pancakes for her handsome lawyer husband and four cute kids, only to be dragged back into the fray by Trump’s itchy Twitter finger. When Steve Bannon enters the room, she recoils in horror. She is constantly burying her face in her hands.

The SNL Conway is a liberal fantasy, a vision of a secretly sane woman who can’t abide the vile creature she so vigorously defends. (Also see: Ivanka Trump.) In reality, Conway is close with Bannon—he reportedly accepted the Trump campaign CEO position in August on the condition Conway be hired as well—and they both share ties with conservative hedge fund manager and Breitbart investor Robert Mercer. On TV, her cloudless, near-psychotic self-confidence never wavers. Behold the beatific joy that suffuses her face when the hosts of The View ask her about Trump’s fat-shaming of Miss Universe Alicia Machado. “I’m sure that on your Twitter feed right now you have viewers discussing my looks and my intelligence,” she beams, apparently delighted at the thought. “I never knew how ugly and stupid I was until Twitter!”

Conway is no lion tamer, either. The president-elect’s senior counselor has not and will not moderate Donald Trump’s views. Rather, she markets his lies, evasions, and personal attacks better than he ever has himself, transforming his latest fetid PR squash into a horse-drawn carriage equipped with diamond-encrusted wheels and coachmen tipping Make America Great Again chapeaus. Conway, who appears to believe in nothing, is a Meryl Streep–caliber performer of true belief. Her conviction is as unshakable as it is ephemeral, at once adamantine and erratic. She’s a feminist and a mouthpiece for anti-woman policy, a bulldozer and a ballerina. She is a strategist who believes successful campaigns are about “values and vision, not just trying to make the other person look like he takes the wings off of butterflies” and an operative who, pressed on Trump’s ties to Putin, fires back, “What has the current president done vis-à-vis Russia for the past eight years that makes you proud?” She is a solid, a liquid, and an ignoble gas.

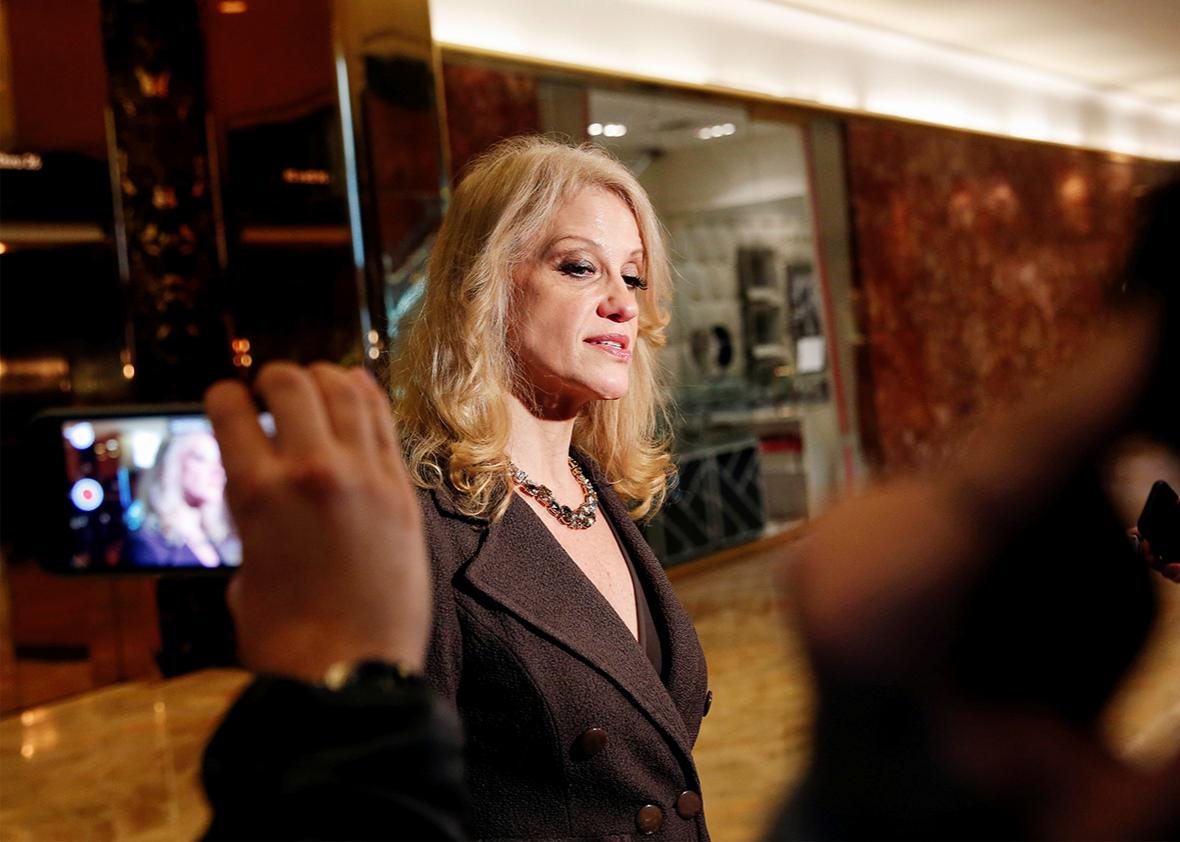

When Streep attacked Donald Trump at the Golden Globes, the president-elect’s fairy godmother shimmered into the picture. There she was, speaking to Chris Cuomo on CNN, rose lips and eye shadow matching her sparkly pink sweater, blond hair tousled in Glinda waves. She knit her brows and enumerated all the ways in which her boss had been mistreated by the craven liars in the press. “Why don’t you believe him?” Conway asked, looking genuinely sad and confused. Trump had not mocked a disabled reporter on the campaign trail, she insisted. (He clearly had.) “You can’t give him the benefit of the doubt on this, and he’s telling you what was in his heart?” Conway shook her head, dismayed. “You always want to go by what’s come out of his mouth rather than look at what’s in his heart.”

On Fox and Friends, Conway rematerialized with a different parry. In criticizing Trump’s mockery of the journalist, she said, Streep had “incited people’s worst instincts.” “The election is over. She lost,” Conway continued, echoing her curt dismissal of Hillary Clinton staffer Jennifer Palmieri, who was concerned about white nationalist Trump supporters. The stars “in their gazillion-dollar gowns” were “of a single, myopic mind of how they wanted the election to go.” “They lost,” Conway repeated.

Two televised statements in defense of the indefensible, each ridiculous and brilliant in its own way. While the Fox spot wins for sheer chutzpah—it’s surprising Conway didn’t suggest that the Southern Poverty Law Center track the rise in hate crimes since Streep’s Golden Globes speech—her remarks on CNN were more peculiar. They conjured the notion of a Trump Tower capsule where operatives practice living in a zero-reality environment. How are we supposed to know what the president thinks except by listening to what he says? Enter Kellyanne Conway to wave her wand and convince us that up is down—unless it’s Tuesday, in which case up is green, down is blue, and sideways is Mexico Will Pay for It.

Conway, who arrived at Mercer’s exclusive “Heroes and Villains” party dressed as Supergirl—her sidekick, Donald J. Trump, was costumed as himself—sees herself less as a fairy godmother than a fairy-tale princess, albeit one whose foot slips comfortably into whatever slipper she’s asked to try on. “Early in her career,” Ryan Lizza reported in an October New Yorker profile, “Conway was invited to [the law firm] Black, Manafort, Stone’s Christmas party, and, she said, ‘It was, like, What am I gonna wear? It was like Cinderella.’ ” In an interview last month, Conway said, “When I stand with all the Trump women … I feel like Cinderella before the ball.”

The Republican pollster and strategist comes by her I-ain’t-the-belle-of-the-inaugural-soirée routine naturally. Raised in the Garden State by a blue-collar single mother and two unmarried aunts, she was “not encouraged or allowed to complain or talk about what we didn’t have.” Thirty-five years later, she is smart enough to know that it’s bad form to talk about what she does have. She has been romantically linked to several marquee names in the GOP (including a former client and Sen. Fred Thompson), has graced the cover of society magazines, is married to a prominent lawyer with Roman numerals after his name, and lives in America’s second most expensive ZIP code. As an anonymous adviser told Lizza, former campaign manager Corey Lewandowski alienated the Trump children “because they thought [he] was becoming too familiar. … He started regarding himself as another Trump child.” Conway would never make that kind of gauche mistake. She knows her place, and she knows how to be all things to all people. (As a teenager, she was both the 1982 New Jersey Blueberry Princess and a champion blueberry packer.)

Conway is skilled at deploying feminine sweetness and light, as when she brightly observed that “Democrats became super-duper interested” in Russian hacking only after they lost the election. Grilled by Rachel Maddow or Whoopi Goldberg, she never gets angry—just “concerned” or “curious” or “disappointed.” (Her decorous language hasn’t stopped fans from compiling reel after reel of quips from “the comeback queen.”) She invokes retrograde ideas about gender when they suit her, telling Fox host Maria Bartiromo that she’s better equipped than most men to juggle her family and her career because “I don’t play golf and I don’t have a mistress.” She’s also labeled herself “a man by day.” And yet, after former Mitt Romney strategist Stuart Stevens made fun of her post-debate television appearances, Conway said his comment “smacks of misogyny.” And she’s dramatized her lonely ascent through the “male-dominated” poll business to become the first woman to lead a Republican presidential campaign—a career arc she insists reveals Trump’s pro-woman credentials.

Brought up in a household of female Catholics, and fervently pro-life, Conway founded a polling company in 1995 that works primarily with Republicans seeking to make their views palatable to women. Her clients have included Newt Gingrich, Mike Pence, the National Rifle Association, Steve King, the Family Research Council, and Todd Akin, who tested her public relations sorcery when he attested that the female body could “shut down” the seed of “legitimate rape.” Conway was a fixture on cable news panels during the ’90s, unraveling the mysterious psyche of the soccer mom and explaining why Florida conservatives hate trial lawyers. While Ann Coulter and Laura Ingraham cast themselves as provocateurs, ’90s-era Conway—who then went by her maiden name, Kellyanne Fitzpatrick—dispensed facts and figures, not opinions. In 2010, she teamed up with Democratic pollster Celinda Lake to write a book entitled What Women Really Want: How American Women Are Quietly Erasing Political, Racial, Class and Religious Lines to Change the Way We Live. In the introduction, the authors divide America’s second sex into archetypes: Feminist Champion, Suburban Caretaker, Multicultural Maverick, Senior Survivor. Each prototype gets her own worldview, a synthesis of political inclinations and consumer preferences. Conway’s job was not to judge, but to tally and illuminate—to help rather than to fight—an orientation that serves her well as she tries to temper the edges of the most bellicose man in American politics. Her Twitter bio, from which she lobs snippy witticisms at her opponents, reads, “Blessed. Fortunate. Ready to serve.”

Early in the 2016 election cycle, Conway served Ted Cruz. As recently as April, she criticized Trump on her ex-boss’s behalf, calling his personal attacks “fairly unpresidential.” When Cruz’s electoral fortunes fell, she jumped to Trump, stressing that both men represented an alternative to the Republican establishment. Conway has shown some signs that her loyalty has its limits. When Trump was reportedly considering Mitt Romney as secretary of state, she appeared on Meet the Press to bash the former Massachusetts governor as “nothing but awful.” The press wrote breathlessly of the counselor who’d “gone rogue,” though Conway protested that she had no intention of “boxing [her boss] in” and had been encouraged by Trump to go public with her views.

This, again, felt less like bold truth-telling than a shrewd performance of independence, a signal that Conway, no lackey she, speaks from the heart and deserves our trust. Conway has two jobs—intuiting and delivering what her employer wants, and intuiting and delivering what we want—and thus far she’s excelled at both. Her ultimate allegiance, as befits someone who got her start in commercial polling, is to a vision shaped by consumer desires: She has to convince both Trump and the American people that we’re living in the best of all possible worlds.

On Charlie Rose in 1996, Kellyanne Fitzpatrick looked pert and impeccable, her plucky spirit dancing across her expressive face. At the barest prompt from the host, she released a stream of melodious chatter on “at least three very solid indicators” that the American people would usher Republicans into Congress and a Democrat, Bill Clinton, into the White House. “We talk a very good game about change … in this country,” she said, letting viewers in on a secret, “but we still love incumbents.” We’ve “very much bought into Bill Clinton’s ideal of ‘don’t rock the boat.’ ”

I watched this clip and fantasized about shuttling this version of Kellyanne Conway 20 years into the future, so she could debate herself on the state of Clintonian ideals and the American people’s need for transformation. The old Kellyanne and the new Kellyanne share the same disarming smile and thread verbal needles with the same facility. Conway has always shined at her job, no matter which side of her mouth her words are rivering out of. Her constant inconstancy is almost comforting, in its way. Why demand moral coherence from a magic show? Vaseline will never give you an honest take on diaper rash. It’s too busy covering someone’s ass.