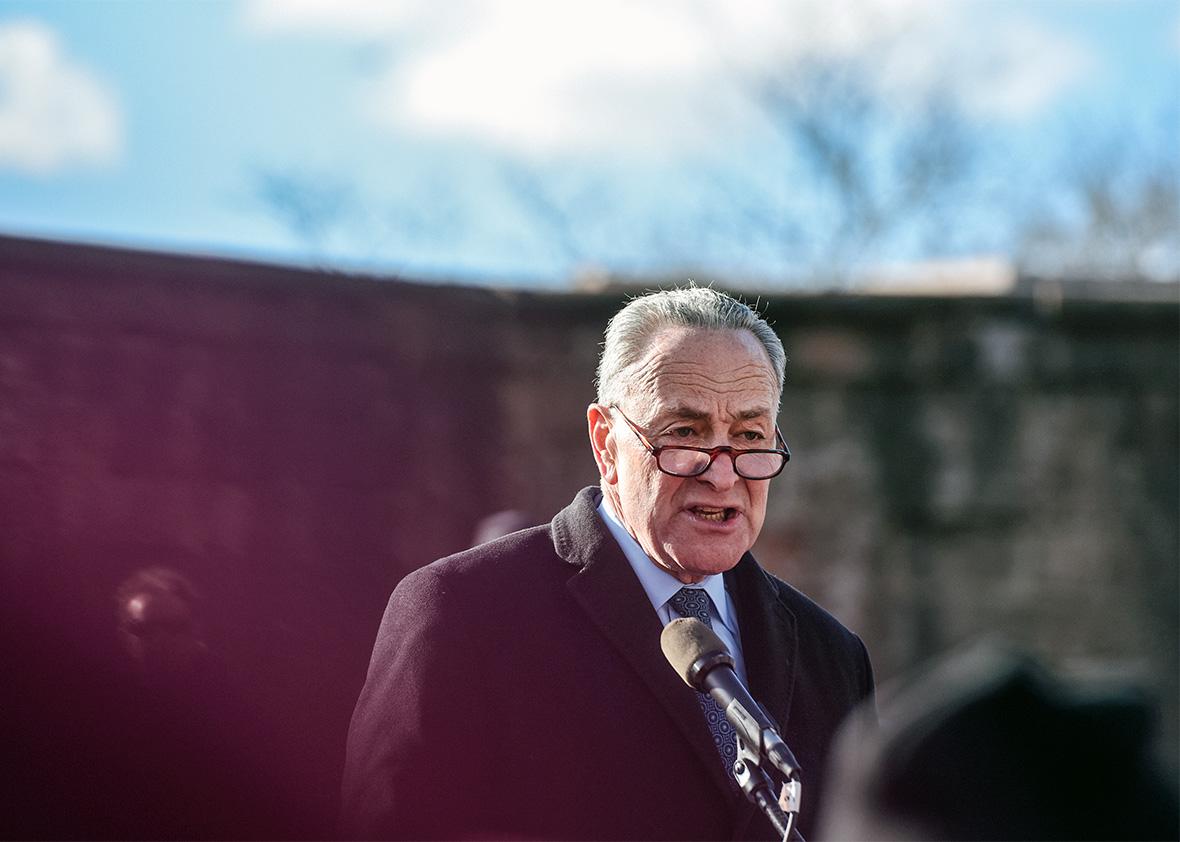

On Monday afternoon, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer announced, via Facebook, that he would oppose most of Trump’s Cabinet appointees. First, he reiterated earlier promises to vote against Betsy DeVos for education secretary, Rex Tillerson for secretary of state, and Jeff Sessions for attorney general. “Nothing will change that,” Schumer wrote, adding that he’d also resolved to vote against Mick Mulvaney for budget director, Tom Price for secretary of health and human services, Steve Mnuchin for treasury secretary, Scott Pruitt for head of the EPA, and Andy Puzder for secretary of labor. These men, wrote Schumer, “have repeatedly shown they will not put the American People or the Laws of our nation first, and I will vote against their confirmations.”

As soon as I saw Schumer’s announcement, I checked in with Elizabeth Zeldin and Hae-lin Choi, Brooklynites who are organizing a demonstration outside of Schumer’s Park Slope apartment on Tuesday to demand that the New York senator resist Trump more firmly. “It’s working!” Choi messaged me back, adding that she and Zeldin are “heartened but not mollified.” Their event—titled “What the F*ck, Chuck?!”—will continue as planned, though now the tone is likely to be one of encouragement as well as reproach. “Chuck Schumer, we, your constituents, are looking to you as Senate Minority Leader and our Senator, [to do] more, to do it stronger, and to keep up the tough fight ahead!” says the demonstration’s Facebook page. More than 3,500 people have said they’ll be there.

Since Trump’s election, progressive activists have been seething over Democratic collaboration with the new administration. True, Democrats have done more to oppose Trump’s nominees than Republicans did to stall Obama’s picks. But as many on the left see it, it’s a mistake to compare Obama—a popularly elected president who chose qualified people for his administration—to Trump, a minority president and despotic extremist. Among the Democratic base, “there is a huge amount of anger and disbelief,” says Ezra Levin, one of the authors of “Indivisible: A Practical Guide for Resisting the Trump Agenda,” a viral document by former Democratic congressional staffers that offers a blueprint for creating a Tea Party of the left. “The idea that we can treat this administration as if it is normal, as if it is not actively undermining democracy, is really inappropriate to the moment. And I think the base feels that.”

All over the country, grassroots organizations (many inspired by “Indivisible”) have been forming to insist that their representatives obstruct and oppose Trump at every turn. The “Indivisible” website lets people register their groups, and so far more than 4,000 have. MoveOn.org, the Working Families Party, and People’s Action have declared weekly Resist Trump Tuesdays; according to MoveOn, more than 10,000 took part in 200 rallies at congressional offices on Jan. 24. Democrats who haven’t resisted Trump strongly enough have had to face enraged voters. On Sunday, nearly 1,200 people showed up for a constituent meeting with Rhode Island Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, many demanding to know why he’d voted for Mike Pompeo for CIA director. “You are entitled to an explanation of why I have voted for some of the defense nominees,” Whitehouse said. “I will concede right off the bat that I may have been wrong.”

There has been particular pressure on Schumer. Many of his constituents were horrified when, in the wake of Trump’s election, the senator spoke optimistically of making a deal with the new president on infrastructure. They were appalled when, in his response to Sessions’ nomination, Schumer pointed out that they work out together in the Senate gym. “He’s in a very tough place,” says Zeldin. “I do not envy him right now. But as his constituents, we need to make sure he’s much more of a fighter than he’s been.”

Zeldin exemplifies the new wave of “Indivisible” activism. A 37-year-old from Brooklyn, she says that before Trump’s election, she could have counted the number of political rallies she’d attended on one hand. Afterward, she was desperate to do something and was inspired by the “Indivisible” guide’s advice to focus on your own representatives. Members of Congress, the guide says, “are enormously sensitive to their image in the district or state, and they will work very hard to avoid signs of public dissent or disapproval.” Zeldin had felt powerless in what she calls her “blue bubble.” Realizing she could do something useful in her own city “was super affirming and super helpful. I don’t have a red representative who might change his mind, but I do have a blue representative that is actually super powerful and has a lot of say if he chooses to use it.”

Eager to start something, Zeldin called Hae-lin Choi, an activist friend whose son had attended daycare with her daughter. Choi, who works for a union and is a member of Democratic Socialists of America, enlisted help from seasoned progressive organizers. They rallied outside of Schumer’s apartment for the first time on Jan. 10, in concert with Resist Trump Tuesdays. That rally drew around 300 people. It also turned out to be one of three demonstrations in a row outside Schumer’s home that week, all organized by different people and all demanding greater resistance to Trump.

Since then, rallies outside of Schumer’s house by various groups have become a fairly regular occurrence. Meanwhile, City Councilman Brad Lander has been holding massive anti-Trump organizing meetings at a Park Slope synagogue, Congregation Beth Elohim, where Schumer happens to be a member. (The most recent one drew 800 people.) Naturally, some attendees have focused on pressuring their neighbor, joining rallies outside Schumer’s home and office, calling his office incessantly, and delivering stacks of letters imploring him to oppose Trump’s nominees.

Schumer was clearly paying attention. On Jan. 26, he posted on the “What the F*ck, Chuck?!” Facebook page: “Appreciate hearing from everyone on this and on so many of the issues we will face in the weeks, months and years ahead. Wanted to share that on the upcoming vote confirming Betsy DeVos for Education Secretary, I will vote no and I will do it proudly.” Two days later, he was back on the page posting about his plans to vote against Tillerson. Commenters were pleased but urged him to do more. “Thank you – but we need you to oppose them ALL – especially Puzder, Mnuchin, Pruitt,” one said. “THIS IS NOT NORMAL. DO NOT GIVE TRUMP AN INCH!” For the moment, at least, it appears that he won’t.

“Our theory of change here is that the power that any individual local activist has is constituent power. The effective place for you to spend your energy is on whoever represents you,” says Levin. It’s a theory that’s looking better and better.