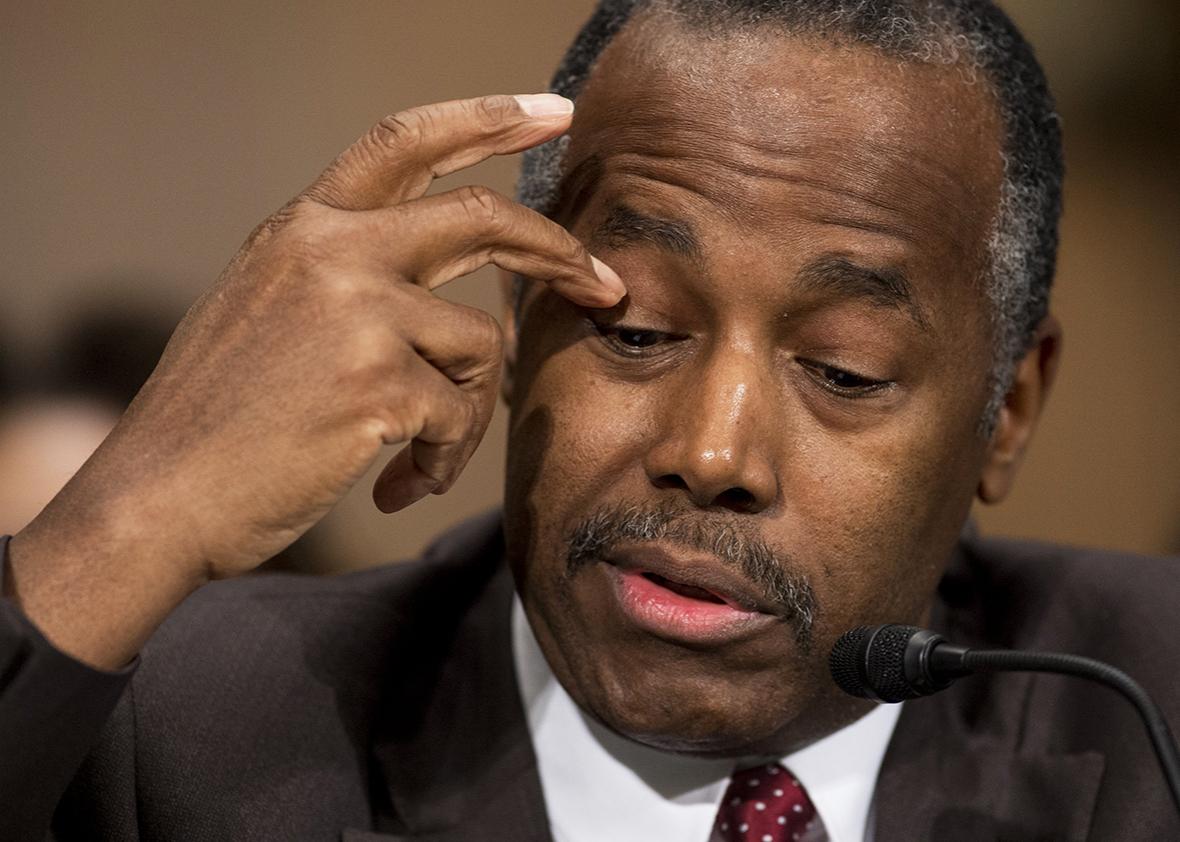

President-elect Donald Trump’s nomination of Ben Carson for Secretary of Housing and Urban Development was not on anyone’s Cabinet secretary bingo card. Best known for his achievements as a pediatric neurosurgeon and celebrated by social conservatives for his opposition to abortion and same-sex marriage, Carson has never devoted much attention to the wisdom of federal housing subsidies, federal efforts to promote racial integration, or any of the other issues at the heart of the HUD portfolio. Indeed, there were reports that Carson was reluctant to accept any Cabinet position. One cynical interpretation is that Trump sees “housing and urban development,” like “urban contemporary,” as a euphemism for “black” and that the sum total of Trump’s thinking about HUD was that he should name a prominent black ally as its head.

But who knows? Having won the GOP nomination on the strength of his outsider status, perhaps Trump believes that only an outsider can shake up HUD and ensure it does a better job of serving the American public. And as someone raised in subsidized housing in a high-poverty neighborhood in Detroit, Carson may bring a level of empathy and insight that will serve him well in his new role. That’s not the view of Carson’s critics on the left. Joan Walsh of the Nation, for example, warns that he might undermine HUD’s desegregation efforts and reverse the Obama-era push to broaden HUD’s focus from housing itself to the role housing can play in fostering opportunity.

What would it take to prove Carson’s critics wrong? Might he somehow manage to reconcile Trump’s nationalist credo with the priorities of urban reformers? Probably not. Voters in America’s big cities overwhelmingly rejected Trump, and it is hard to imagine that he, and by extension his HUD secretary, will expend much effort to win them over. Nevertheless, it is possible to imagine a housing agenda that would speak to Trumpist themes and better the lives of America’s working- and middle-class families.

To massively oversimplify matters, in the presidential election, Hillary Clinton did best in dense, populous cities and inner suburbs while Donald Trump did best in low-density outer suburbs, small metro areas, and rural America. And for the most part, America’s densest, most populous metros are also its most affluent and productive. There’s a case to be made that rising regional inequality has contributed to America’s decadeslong political polarization and to the discontent that fueled Trump’s victory. Carson might consider using HUD as a vehicle to do something for people living in America’s low-income regions, either by improving life in these places or by helping those who live in them move to better-off regions.

Since 1970 or so, there’s been a sharp divergence in the economic fate of regions where the average level of educational attainment is high and regions where the average level of educational attainment is low, as Berkeley economist Enrico Moretti documents in his 2012 book The New Geography of Jobs. There are many theories as to why this is the case. One of the more obvious is that highly educated regions are home to more innovative and productive firms, and these firms attract even more educated workers who in turn drive further productivity increases. Once you have a concentration of educated workers, businesses spring up that cater to their tastes and interests, which makes those regions even more attractive. Sure enough, regions that started out with a large share of college-educated adults in 1970 have attracted more and more of them over time.

It’s important to keep in mind that it’s not just the highly educated who’ve benefited from being surrounded by other highly educated people. To the extent that a high share of college-educated adults in a given metro area contributes to higher productivity levels, it will raise the productivity levels of all workers in said metro, including those with lower skill levels. If I’m a service worker in Palo Alto, California, every hour I save for a high-paid professional who hires me is worth more (in a strictly dollars-and-cents sense, mind you) than every hour I’d save for a lower-paid professional in Bakersfield. This higher productivity level translates into higher wages—richer people are willing and able to pay you more than poorer people for buying them the same amount of time.

Normally, you’d think that the persistence of a wage gap between America’s Palo Altos and Bakersfields wouldn’t last forever, because people would move from the Bakersfields to the Palo Altos until the wage gap disappeared. Not so. If anything, we’ve seen people moving from high-productivity regions to low-productivity regions rather than the other way around, as Ryan Avent observed in The Gated City.

What gives? In a brilliant new working paper, David Schleicher of Yale Law School explains that poor people in poor regions face two different kinds of obstacles: “entry limits” imposed by privileged regions and “exit limits” imposed by poor regions.

The “entry limits” are relatively straightforward. People have to live somewhere, and the most privileged regions have not, as a general rule, constructed anywhere close to the amount of housing they’d need to build to accommodate increased demand. What happens when you limit supply in the face of increased demand? Housing values soar, which is of course a very good thing for incumbent property owners. On one level, you could say that it’s not the federal government’s business if California homeowners vote for stringent land-use regulations that choke off increases in housing supply. Sure, they’re locking poor people out of the region and low-income Californians are four times as likely as other Americans to live in crowded conditions. But that’s their problem, right? Not exactly. Because low-income Californians have to spend such a high share of their incomes on housing, they’re more likely than low-income people elsewhere to be eligible for federal rental subsidies, which are paid for by taxpayers across the country. Moreover, there is good reason to believe that the entry limits imposed by productive regions are damaging America’s growth prospects.

Land-use regulations aren’t the only obstacle to families looking to move to higher-productivity regions, of course. This leads us to “exit limits.” Henry Olsen of the Ethics and Public Policy Center has called for “a new Homestead Act” that would address an equally vexing challenge, which is that America’s decentralized welfare state can make it hard for poor people to move. If you depend on Medicaid or federal housing vouchers, complicated eligibility rules can keep you tethered to your current home.

There is only so much even the most inventive HUD secretary could do about the entry and exit limits that keep so many poor Americans stuck in place. Schleicher surveys some of the more plausible policy changes, and though he allows for the possibility of a federal role, much of the action will have to take place at the state and local level.

A Trumpist HUD secretary could, though, make use of the bully pulpit. Railing against Silicon Valley and Hollywood elites that are building regulatory walls around their neighborhoods—all while railing against Trump and his allies for wanting to build a wall around the country—might make for the perfect Trumpist crusade.