When you win, you look strong, and right now, Donald Trump looks strong. He has the White House, and his allies in the Republican Party hold both chambers of Congress. The House is set to pass a sweeping agenda that would gut the safety net, and the Senate is set to confirm hard-right jurists to the federal bench, including to the Supreme Court.

If Democrats held a majority of governorships or state legislatures, the picture would look a little different. But they don’t. Over the eight years of Barack Obama’s presidency, the party has suffered historic losses at the state and local levels. Some of this was the result of poor party leadership from Obama and other figures in Washington; some was demographic, as the Democratic Party relies more on a young, diverse, and less consistent electorate; and some was the final leg of the South’s transition to an almost solid wall of red. Either way, Democrats are in dire straits, fighting a defensive battle against a newly invigorated Republican Party.

But we shouldn’t exaggerate the state of play. Neither Trump nor congressional Republicans are as strong as they appear. Both enter the field with severe disadvantages, and both risk overplaying the hands that they have. Democrats are on the defensive, but the conditions are there for pushback and resurgence.

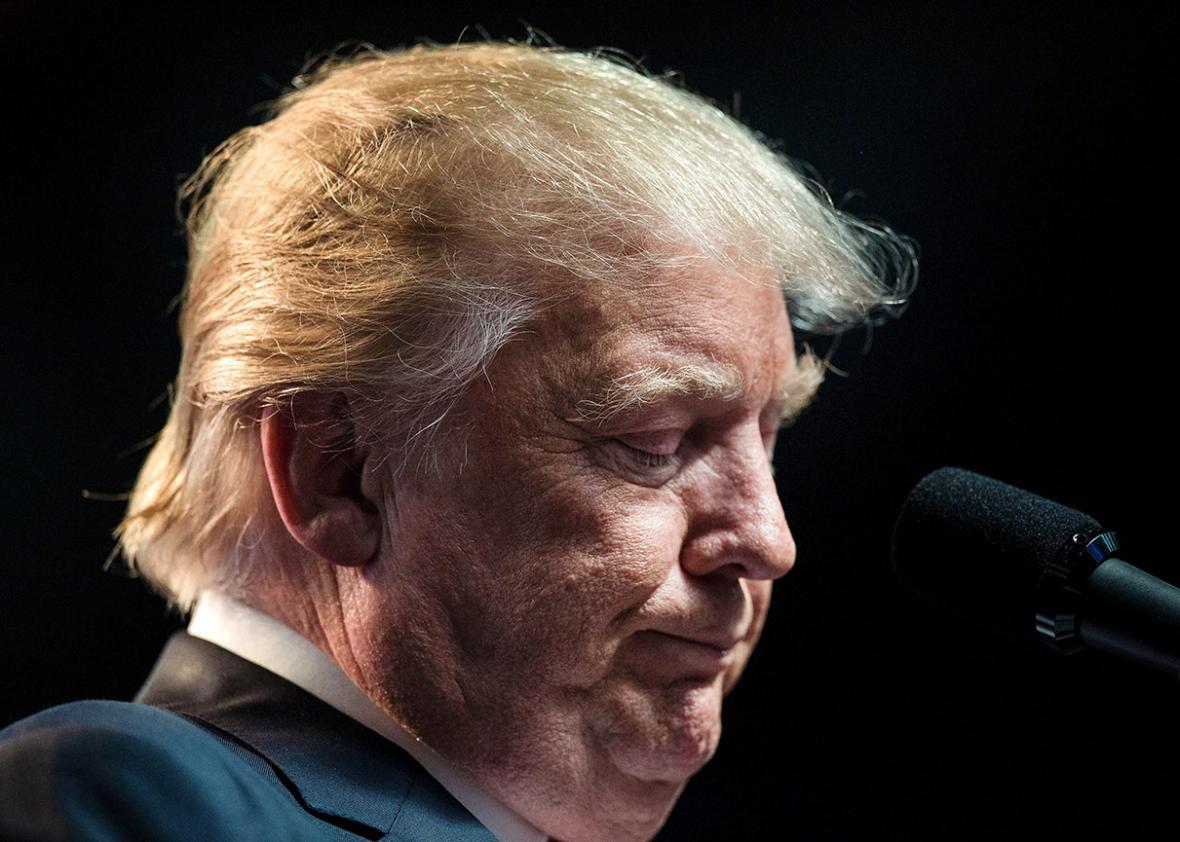

Consider Trump’s favorability rating. On Election Day, just 38 percent of Americans had a positive view of Trump, against 60 percent with a negative view. Now, with the glow of victory, his average favorable rating stands at 43 percent, while 49 percent view him unfavorably. For comparison’s sake, Barack Obama entered office in 2009 with a 68 percent favorable rating versus 21 percent unfavorable, while George W. Bush—the victor in a contentious election decided by the Electoral College—entered office with a 50 percent favorable rating. Trump is historically unpopular for an incoming president and shows no signs of improving. This, coupled with his substantial loss in the national popular vote, is a potent vulnerability. Democrats can credibly say that Trump lacks the “will of the people.” They can rebuff charges of obstructionism, and they can say, with little exaggeration, that the public is on their side.

To Trump’s personal unpopularity, you have to add the unpopularity of the Republican policy agenda. Citing Trump’s win as a victory for conservative governance, House Speaker Paul Ryan and the Republican majority are prepping a sweeping small-government agenda, including tax cuts and repeal of the Affordable Care Act. But there’s a problem. The 2016 election wasn’t fought over policy; it was a battle over values and priorities (it’s likely Hillary Clinton made a fatal strategic mistake in not making this a fight over policy). And throughout, Trump showed little interest in conservative policymaking or conservative ideas. He promised help for his supporters and “better deals” for the country, not a Ryan-esque agenda of lower spending and upper-income tax cuts. That agenda is hugely unpopular: Substantial majorities support greater taxes on high-earners, while a smaller majority backs a more active government role in reducing income inequality. And although Americans still disagree about the Affordable Care Act, most of them still reject repeal.

Intoxicated and emboldened by their near-miraculous victory, Republicans are rushing into the new year with a divisive and unpopular agenda, led by a divisive and unpopular president. Indeed, with no apparent plans for increasing manufacturing jobs or improving veterans’ health care, Trump shows few signs of delivering on his substantive promises. In all likelihood, he’ll offer rhetoric and scapegoats and stunts, while delivering little in the way of tangible gains. And all of this will exist against a backdrop of corruption and influence-peddling, as Trump refuses to disentangle himself or his children from their opaque and sprawling web of business interests.

None of this guarantees that Trump will lose support. Trump has a strong core of voters who, as we saw during both the primaries and the general election, refuse to abandon a figure who speaks for their resentments, their anger, and their frustration. But Democrats don’t need that core. They don’t even need the typical Trump voter (i.e., a Republican). All they need is the marginal Trump voter. The person who flipped from one side to the other. Who cast a ballot for Barack Obama, then turned around to vote for Trump. Who disliked both candidates but went with “change” instead of continuity.

We can argue about their motivations and beliefs. What is true, however, is that among those voters, Trump is not as strong as he looks. He’s vulnerable. If Democrats can mount an effective opposition—rallying in defense of core priorities, forcing confrontation and dramatizing the stakes of every battle, organizing at the local and state levels—they can capitalize on these glaring flaws. They are the weak spots that threaten the structural integrity of Trump’s political project and the fortunes of the Republican Party itself.