Since the election, the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, chaired by Utah Rep. Jason Chaffetz, has been clear about whom it intends to investigate under the new administration: Hillary Clinton, an unemployed resident of New York state’s charming Chappaqua hamlet. Regarding the president-elect’s many conflicts of interest, though, the oft-chatty Chaffetz and his staff have maintained an atypical public silence.

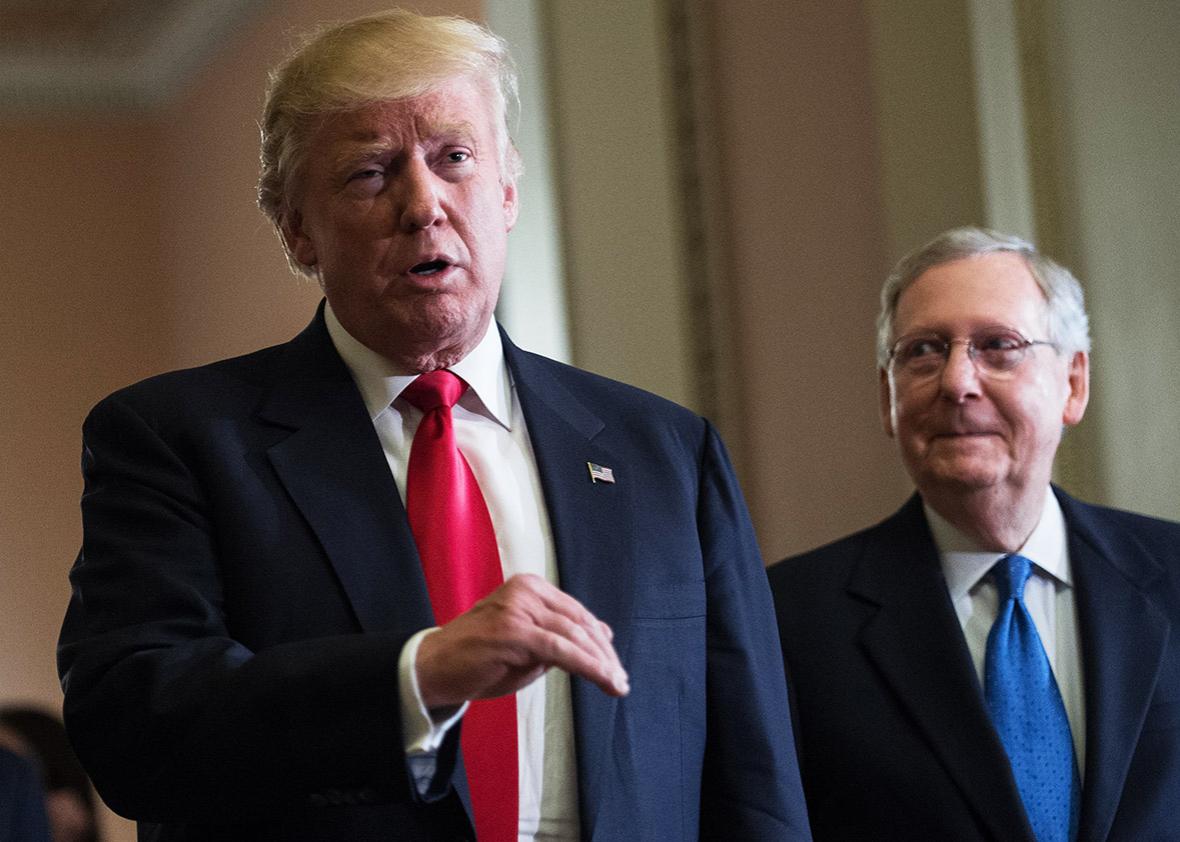

It may be that Chaffetz and other Constitution-worshipping members of the Republican Congress are still debating when to go public with their plan to nail the president-elect on the Emoluments Clause, to maximize damage. Then there’s another possibility: Donald Trump is the incoming Republican president, and Jason Chaffetz is a Republican. Most Republican voters like Trump, and even those who are wary of him at least want to give him a chance to back up his talk. Maybe the Oversight Committee will bend to pressure and hold a quick hearing on a Friday during the holidays. But it won’t hold serious hearings until Trump’s ethical baggage becomes its political baggage, and that probably won’t happen until Trump is already unpopular enough for the ethical stuff to stick.

As a businessman with various international holdings and contracts who also tends to conduct a highly personalized brand of politics, Trump is rife with conflicts of interest for which he never drew up a serious divestment plan. And real-life, oversight investigation–worthy reports of potential malpractice started accumulating as soon as Trump began taking congratulatory meetings and phone calls with foreign leaders. In a meeting with UKIP leader Nigel Farage, the president-elect mentioned how much he hates the idea of wind farms spoiling the view of his Scottish golf course. He let his daughter Ivanka, who has no role in the administration but does continue to help the family business, sit in on a meeting with the prime minister of Japan. A New York Times investigation this weekend found that the president-elect “has business interests in at least 20 countries, in addition to extensive hotel and real estate holdings in the United States, according to an analysis of his financial disclosure report.”

Argentina is one of those countries, and an investigative journalist there said—“half joking, half serious”—that Trump and Argentine President Mauricio Macri discussed permits for a long-stalled, $100 million Trump complex in Buenos Aires in their post-election chat. Both Trump’s campaign and Macri have denied any such conversation took place. Even if it didn’t, there’s still the problem of Trump’s conflict of interest in that country. “Even if the president isn’t so ham-handed as to actually ask foreign leaders to advance his bottom line,” my colleague Henry Grabar wrote, “they know what they can do to help.”

It’s well within the jurisdiction of Chaffetz’s Oversight and Government Reform Committee to examine reports of an incoming president using his official power to influence decisions affecting his international business empire. One might even say it’s his job. I understand that Chaffetz might need some time to reorient himself, after spending much of the pre-election period prepping for “years” of investigations into the second President Clinton. We’re all straining to adjust to the unreality. But Chaffetz’s spokespeople were mum when the Republican’s Democratic counterpart on oversight, ranking member Rep. Elijah Cummings, issued a letter two weeks ago calling on him to investigate Trump’s conflicts of interest. Chaffetz’s office was without comment, similarly, when I asked about the Argentina story last week. When I asked Monday whether there were any sort of statements coming about a possible investigation into the president-elect’s tangle of holdings, I received no reply. Cummings and fellow Democrats on the committee issued another, lengthier letter on Monday reiterating their call for an immediate investigation.

Before considering what Chaffetz will do, let’s first consider who he is. He’s a character, typically accessible and excited to yuk it up about all the hearings he’s planning. Then there’s the other Chaffetz, the one who endorsed Trump once Trump became the nominee, unendorsed him soon after the Access Hollywood tape came out, and later tweeted, as Trump began to rebound in the polls, that he would not “defend or endorse” Trump but would vote for him, because “HRC is that bad.” Who is Jason Chaffetz? He is the Republican chairman of the House committee overseeing the incoming Republican president, who is popular among Republicans. For now, that’s that.

Congressional Democrats are going big on Trump’s conflicts of interest. They might as well, because it’s a meaningful subject that deserves scrutiny, and because they have little else to do. Since Republicans, with a few exceptions, will be politically constrained from going after the many, many ethical questions surrounding their new leader, the criticisms will neatly separate Republican actions from the principles they espoused while harassing the Clintons for 25 years.

Hypocrisy points don’t count for much, though. Especially with this president. The potential conflicts of interest Trump would face as president got plenty of coverage during the campaign, and he was elected anyway. Voters might take potential conflicts of interest more seriously once they blossom into real conflicts of interest. Still, they knew, because it was hard not to know, the man they were voting for. And for much of Trump’s base, their man’s ability to get away with fussy things like a disregard for norms and ethics was a significant part of the appeal. They believed it upset the media (it did!) and thought that America needed a tough guy who was willing to bend the rules. Sure, he may skim something off the top for himself. So long as he fights dirty on Americans’ behalf and gets results, though, all’s well.

Trump stops being “our jerk” and simply becomes a jerk only if he can’t get results. If he is unable to bring back jobs, to “build the wall,” to prevent each and every terrorist attack, to stick it to China over currency manipulation, to renegotiate trade deals, to replace Obamacare with something “beautiful,” to stave off a recession that has a decent chance of landing on our doorstep in the next four years, to rebuild the Rust Belt—in short, if he is unable to make America great again—then the ethical questions surrounding his conflicts of interest may begin to stick in a meaningful, nonpartisan way. It will be Democrats’ job to queue the investigations and have them shovel-ready for when Republicans decide it’s in their interest—if not necessary for their survival—to dig in.

Liberals looking for any cudgel to use on Trump would do well to remember which way the causation tends to run in a political scandal, dispiriting though it may be. Trump won’t collapse because he’s the subject of a serious ethics investigation; he’ll become the subject of a serious ethics investigation because he’s already begun to collapse. After all, many of the voters who decided the election for Trump are those who were willing to roll a stick of dynamite into Washington, because the resulting random configuration of rubble might produce something meaningful that the previous institutions couldn’t, or wouldn’t. If the random configuration of rubble produces anything like what we’d expect from a random configuration of rubble, though, then Jason Chaffetz might seriously investigate allegations of corruption in the Trump administration. The political costs of not investigating a failure would be too high.