Once Donald Trump takes office, he will be the most widely loathed president in modern American history. Yet he will also have far more room to maneuver than any of his recent predecessors. That’s precisely what’s freaking so many people out. There is no way to predict what Trump will do or say in the months to come, and that’s left many Americans anxious and afraid.

Normally, you’d expect a successful presidential candidate to be at least somewhat attuned to the interests of his political allies, including his donors. Mitt Romney likely would have run a very different campaign in 2012 had he not depended on the support of wealthy donors. Trump faced no such constraint. His early success was driven largely by the saturation media coverage he generated with his bombastic rhetoric.

This difference shows in Trump’s fundraising totals. Through mid-October, his campaign committee spent roughly half as much as Hillary Clinton’s. And while Romney attracted hundreds of millions of dollars in support from Super PACs, Trump’s Super PAC allies raised a far smaller sum. Several large donors who had enthusiastically backed Republicans in previous elections and who supported Trump’s rivals in the race for the GOP presidential nomination, favored Clinton over Trump. This was particularly true of donors who had contributed to Jeb Bush, John Kasich, and Marco Rubio, three candidates perceived, fairly or otherwise, as especially deferential to the interests of the financial services sector.

If Trump won’t be tied down by large donors, might he instead by hemmed in by the Republican Party? Probably not.

Unlike the centralized, disciplined political parties found in many other democracies, America’s major parties are loose coalitions. Campaign finance regulation has hollowed out central party organizations, and power has shifted to individual candidates, their fundraising networks, and a congeries of Super PACs and pressure groups. The party that controls the presidency has the distinct advantage of having a very visible figure who is unambiguously at the top of the partisan totem pole. Without such a focal point, these loose coalitions have a way of descending into anarchy. That’s basically what’s happened to the GOP in the Obama years.

But now the GOP has a focal point, and it’s not Reince Priebus, the chairman of the Republican National Committee, or Paul Ryan, the speaker of the House (for now, at least). It is Donald Trump. Instead of Republicans reining in Trump, it is Trump who will play the central role in defining what it means to be a Republican.

Until recently, ambitious young Republicans knew exactly what they had to do to make their way in the GOP: Invoke the memory of Ronald Reagan at every turn, even if you were but a small child when Reagan was in the White House, and make sure everyone in the party knew you were a conservative’s conservative devoted to conservative conservatism. Witness the careers of Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, two 40-somethings who hold different perspectives on policy issues and who have entirely different styles. And yet both men endeavored to convince their fellow Republicans, and particularly Republican donors, that they were Reagan’s Latino heirs. Trump’s victory has almost certainly brought the era of Reagan worship to an end.

If donors won’t guide the president-elect, and the party apparatus won’t constrain him, then who will steer the president-elect? Heavy responsibility will fall on the shoulders of Ivanka Trump and her husband Jared Kushner, Trump’s closest confidantes, and the as yet unknown people who will staff senior roles in his administration.

Trump has been consistent on one point over the course of his decadeslong flirtation with national politics: his skepticism about free trade and his commitment to economic nationalism. On almost everything else, from the tax code to universal health insurance to the size of the military to unauthorized immigration—his signature issue this campaign cycle—he’s taken any number of positions. On most of these questions, with the notable exception of immigration, Trump is a blank slate. Indeed, one of his recurring themes has been that, unlike the Republicans he trounced in the primaries, he is no ideologue. He’s promised to do “whatever works” to make America great again.

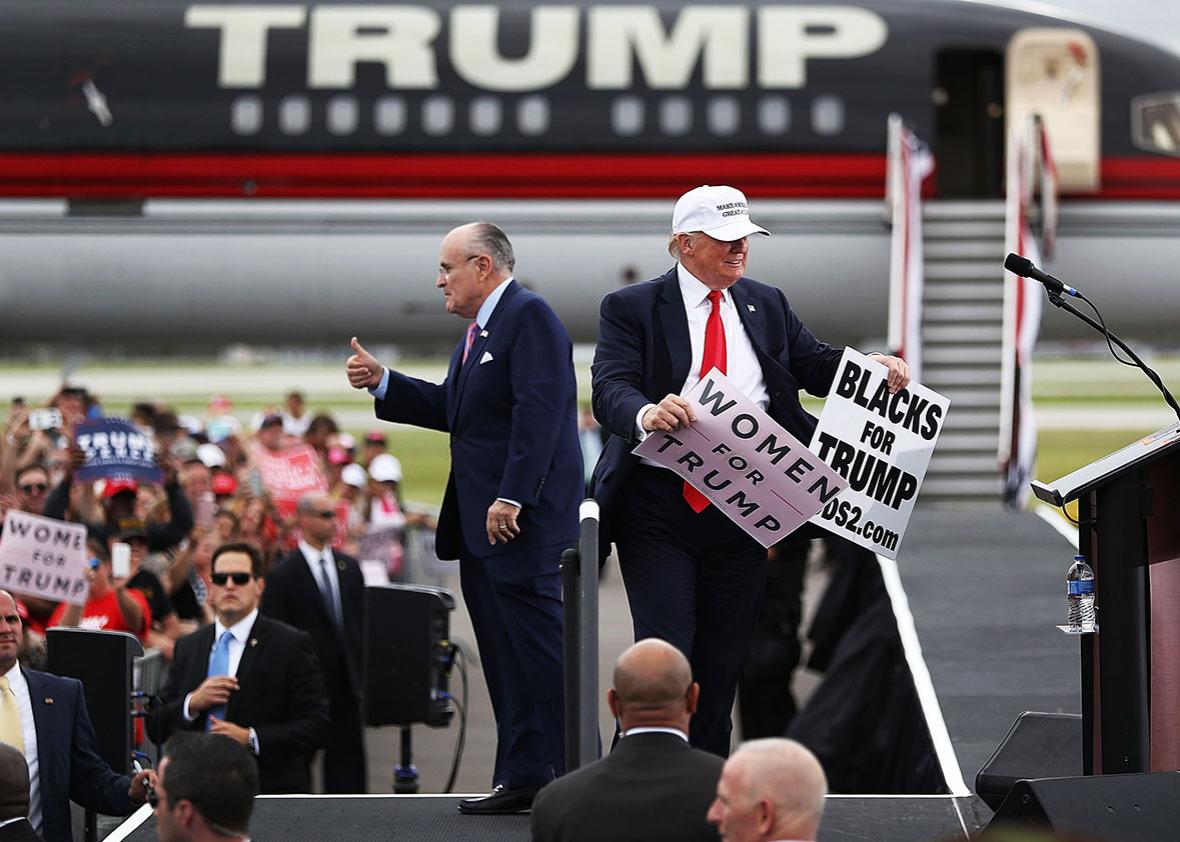

Who will serve in a Trump administration? We can expect that Trump’s most enthusiastic surrogates—former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, former New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani—will be given prominent roles. Trump’s most devoted cheerleaders have been has-beens (like Gingrich and Giuliani) and never-weres who were unafraid of the reputational consequences of backing Trump either because they were so devoted to his cause or, in some cases, because they felt they had everything to gain and nothing to lose.

If loyalty is Trump’s chief criterion for hiring, he’ll run into a serious problem. There are countless roles that will need be filled at the Trump White House and in executive branch agencies, most of which offer sleepless nights and hardly any glory. Because his campaign was so small and because it alienated so many elite Republicans, it will be difficult for President Trump to limit himself to loyalists. He will have to reach out to at least some of the men and women who opposed him.

One of the biggest challenges facing Republicans in the post-Reagan era is that as the party has grown more stridently anti-elitist, it has hemorrhaged college-educated professionals. Though the GOP has compensated for this loss in electoral terms, it’s contributed to an asymmetry in the realm of policy expertise. Whereas Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign had vast numbers of credentialed policy experts at its beck and call, the Trump campaign had a small, tight-knit coterie of contrarians, who zagged when other Republicans of their social class zigged. That’s not a terrible thing when you’re waging war on the conventional wisdom. But it makes life far more difficult when you need warm bodies to fill staff positions. Most people are conformists, not renegades. And in intellectual circles, including in conservative intellectual circles, full-throated support for Trump has been a minority position.

In the weeks and months to come, many policy professionals will face a dilemma. Are they willing to put aside their doubts about Trump to serve in his administration? Doing so will mean taking on a not-inconsiderable risk. Trump was the most polarizing presidential candidate in recent memory. It is easy to imagine that he will be just as polarizing a president. He is untested as a public servant, and it’s not at all clear that he has the discipline or the experience necessary to serve as the nation’s chief executive.

That is precisely why it is so important that those asked to serve in the Trump administration give very serious consideration to doing so, regardless of their political proclivities. This is particularly true of those with national security expertise, but it is not limited to them. America is entering a very uncertain moment, and our new president will need calm voices and steady hands around him.