On Tuesday, Slate—in partnership with the data startup VoteCastr—published running estimates of which candidate was leading and by how much in seven battleground states. The real-time Election Day experiment did not go smoothly.

Technological problems prevented VoteCastr from providing us with those estimates for much of the morning, which made it impossible for Slate to present that information to readers as we had promised. Although we launched the day at 10:30 a.m. with VoteCastr’s estimates of the early vote split, it wasn’t until early afternoon that the turnout data started flowing in from polling places and our vote-tracking visualizations were updating correctly. Even then, there was enough lag time in the process that the information we displayed was updating more slowly than we would have liked—roughly every 30 minutes rather than minute by minute.

We knew presenting a stream of Election Day data would pose technical challenges. Nevertheless, we hoped our partnership with VoteCastr would provide Slate readers with insight into what was happening on the ground and how campaigns assessed turnout in real time. How did VoteCastr do on that front? Not great.

The most obvious way to assess VoteCastr’s performance is to judge its estimates against the actual election results. As you’ll see in the tables below, in most cases those estimates did not match reality when the polls closed. A direct comparison between the last VoteCastr estimates published on Slate and real-world vote totals isn’t entirely fair, however. The numbers presented on Slate portrayed VoteCastr’s assessment of the current state of the race at any given moment on Election Day, not a projection for the final outcome in each state. VoteCastr collected its final batch of field reports in the East Coast states it was tracking at 5 p.m. EST, two hours before polls started closing there, and pushed its final batch of data to us at 6:45 p.m. EST. Why stop in the early evening? VoteCastr says it opted to deploy more field workers for fewer hours rather than use fewer field workers for more hours. Given that one of the project’s goals was to show the public how a campaign boiler room operates, that makes some sense—campaigns are far less interested in the data that comes in toward the end of the day, because there isn’t much they can do with it in those last few hours. What campaigns do is gather robust data early in the day and use it to project both the current state of play and to make projections for the eventual result. Still, VoteCastr’s decision to pull its trackers is difficult to square with its promise of providing civilians with a “play-by-play” look at Election Day.

Voting in those final hours accounts for some of the gap between VoteCastr’s estimates on Slate and the real-life results. In presenting VoteCastr’s data on Slate, we made the editorial decision to show which candidate held the estimated lead in each state at a particular moment in time, not to project who would win once all votes had been cast. But VoteCastr also made end-of-day projections, which it provided to its other media partner, Vice. That set of numbers, like the ones we presented on Slate, also missed the mark in most of the states VoteCastr was tracking.

In the following table, you’ll see the last current vote split estimates that VoteCastr gave to Slate on Tuesday evening:

In this next table, we’ve compiled the final estimated projections that VoteCastr says it presented to Vice on Tuesday evening. These end-of-day numbers represent how VoteCastr believed the vote split would shake out if the trends it had observed up until that point continued until polls closed.

(VoteCastr also analyzed the vote in Colorado, where Hillary Clinton won by 2.9 percentage points and where VoteCastr estimated Clinton had a 2.7-point lead after counting a portion of ballots cast early. But since the majority of votes are cast by mail in the state, VoteCastr did not track real-time turnout there, so Slate did not include those estimates in our interactive.)

The leader in VoteCastr’s end-of-day projections went on to win in five of the seven states it was tracking on Election Day. Five of seven has a nice ring, but it’s difficult to see these results as a success. In only two of those battleground states were VoteCastr’s projected splits within 3 points of the final results. In three, by contrast, its projections were off by 8 points or more. The main takeaway from the numbers above, then, is that in more than half of the states VoteCastr was watching, what it believed it was seeing at 5 p.m. had little in common with how those races looked when they reached the finish line.

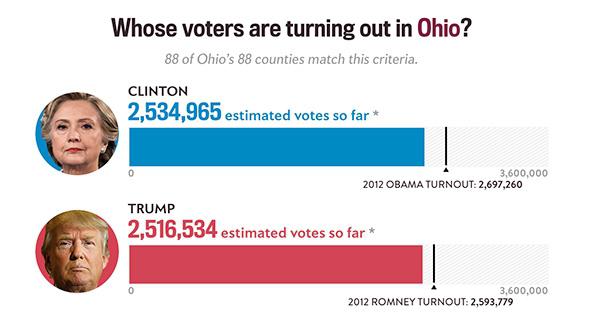

In Wisconsin, VoteCastr saw a comfortable 8-point lead for Clinton. In reality, Donald Trump pulled out a 1-point squeaker there. In Ohio and Iowa, VoteCastr saw dead heats. When the final votes had been counted, Trump had won those states by roughly 9 and 10 points, respectively. And in Florida, VoteCastr saw Clinton up by nearly 4 points, a larger margin than Barack Obama won the state with in both 2008 and 2012. In the end, Trump beat Clinton by a little more than 1 point. Meanwhile, even one of VoteCastr’s apparent successes came with an embarrassing footnote. Of all of its end-of-day estimates, VoteCastr was closest to the final results in Nevada. The company’s model for the state, though, had included Jill Stein despite the fact the Green Party nominee did not appear on the ballot there.

What went wrong? We’ve spoken with several members of the VoteCastr team during the past few days. While none were ready to draw any firm conclusions, they suggested they’d likely been felled by the same Clinton-favoring pre-election polls that caused so many of their fellow number-crunchers (as well as most journalists) to underestimate Trump’s chances. The VoteCastr model involved multiple moving parts, including tracking turnout in select precincts on the ground, then extrapolating those numbers to estimate turnout in areas they were not observing. But Ken Strasma, who served as the microtargeting chief for the 2008 Obama campaign, told us the morning after the election that although there might have been other contributing factors, he believed the difference between his team’s estimates and the actual results “could be entirely due to the polls overestimating Clinton’s support.”

That’s a simple answer to a complicated question, but it strikes us as generally credible. While VoteCastr carried out its own proprietary, large-sample polls, the team told us prior to the election that its numbers were generally tracking with public surveys. The VoteCastr team was up front about the fact that its estimates would only be as good as the models that made them, which would only be as good as the polling data they used. This isn’t Wednesday-morning quarterbacking: When we spoke to the team before Election Day, it said inaccurate polling was one of its biggest concerns.

If respondents weren’t being honest with the pollsters about who they were going to vote for—or if there were a late shift that occurred after the pollsters left the field—any poll-based projections would be doomed. In that regard, at least, VoteCastr has plenty of company. The New York Times’ Upshot, Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight, and every other major poll-based prognosticator saw Clinton as the clear favorite heading into Election Day, and at least one went as far as to suggest a Clinton victory was nearly inevitable—a far more concrete prediction than VoteCastr ever made on Election Day. “It’s not going to be VoteCastr that’s going to explain why everyone’s polling was off,” CEO Ken Smukler told us Thursday morning. “There are huge polling firms with egg on their face today.”

Complicating things, however, is that the accuracy of VoteCastr’s end-of-day projections didn’t all vary from pre-election polling in the same way. In Pennsylvania, VoteCastr’s projection (which saw Trump winning by 2.6 points) was closer to the final returns (Trump by 1.2 points) than an average of pre-election polling in that state (Clinton up 3.7 points). But VoteCastr’s projections were further from reality than the polls were in four of the other states it tracked (Ohio, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Florida), while it missed by roughly the same margin as the polls in the remaining two (Nevada and New Hampshire). It’s possible that the polling problems weren’t spread out uniformly across the nation. Poll respondents, for instance, could have been more honest in some states than others. Right now, all such theories are unproven. Regardless, it’s clear that there’s no specific, one-size-fits-all polling answer to explain the discrepancies between what VoteCastr thought it was seeing and what ultimately happened.

There are other potential reasons for error. VoteCastr’s project was premised on the idea that microtargeting and Election Day tracking could solve one of the biggest challenges faced by pollsters: figuring out how many people would actually show up to vote. By counting turnout at a preselected sampling of precincts on Election Day, VoteCastr believed it could make informed guesses about who was turning out in the rest of that state. That method might have failed to produce reliable results for any number of reasons, from problems with how the field workers collected the data, to a failure by the model to accurately predict which specific voters were the ones turning out. One potential reason for the latter: VoteCastr did not attempt to account for the reality that campaigns and their respective parties prioritize get-out-the-vote operations differently in different places in different elections.

Right now, there are many possible explanations for what happened on Tuesday, but the case remains unsolved. “Thirty-six hours doesn’t provide the right vantage point to assess this stuff,” Sasha Issenberg, the onetime Slate columnist and campaign data expert who helped found VoteCastr, told us on Thursday. He said the company remains committed to performing an empirically sound postmortem to figure out what happened but that it won’t be complete until states update their voter files, a process that can take months.

From the start, we’ve considered the VoteCastr project to be an experiment. It was based on two ideas: First, that there’s no sound reason to keep real-time information from voters on Election Day. Second, that the methodology used by campaigns could prove more valuable and accurate than exit polling in anticipating election results. In the end, VoteCastr wasn’t able to nail the election outcome. But the larger journalistic theory here—that voters who spend elections tracking public opinion polls and assessing analyses of early vote numbers can handle information about their fellow voters’ preferences on Election Day itself—remains intriguing. VoteCastr didn’t work perfectly this time. We still believe it was an experiment worth trying, and we remain open to presenting data to our readers on Election Days to come.