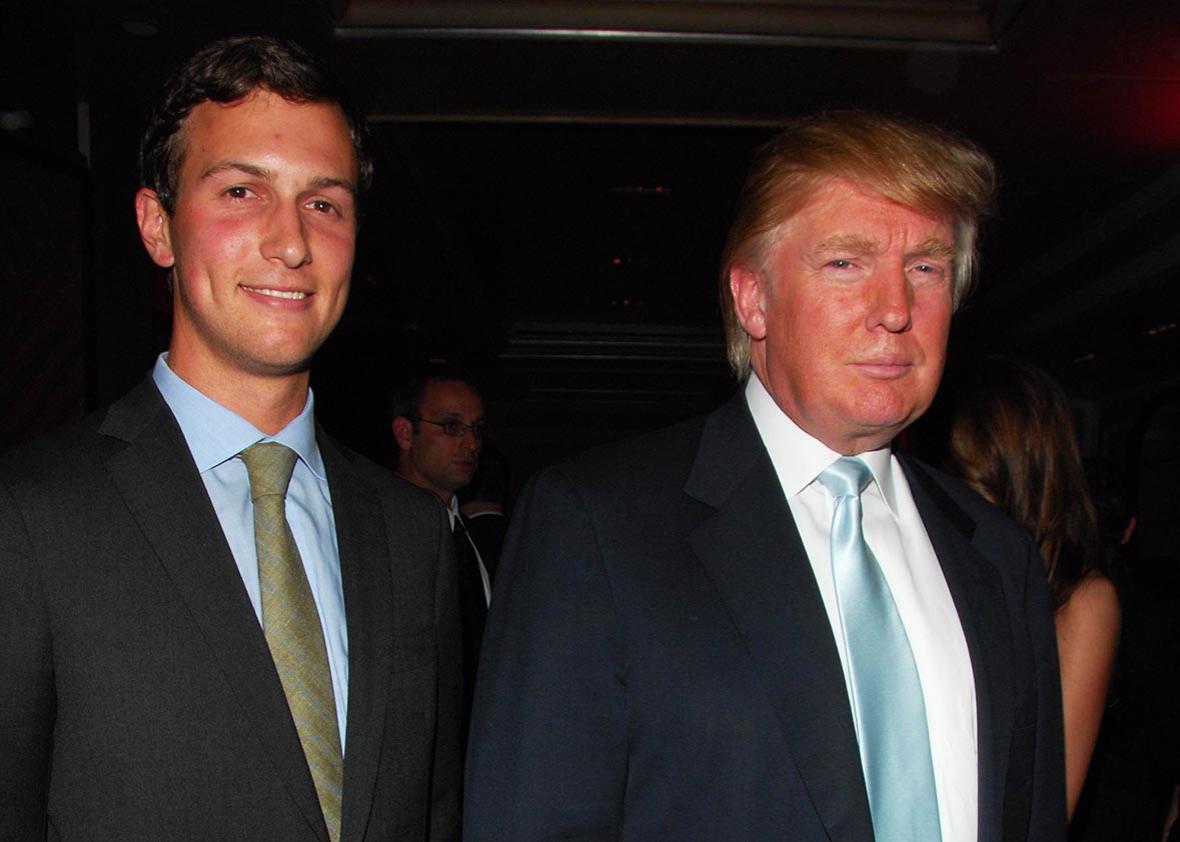

Jared Kushner wasn’t yet married to Ivanka Trump, or trying to help elect her father president, when he bought the New York Observer in 2006. At the beginning, the 25-year-old could only do so much damage: The editors who ran the paper were too good, both at editing stories and at pushing back against the new owner’s short-sighted demands. From my desk in the newsroom—I started at the Observer right out of college in 2007—it was easy to see Kushner as a dim but mostly harmless rich kid whose willingness to spend money on the paper was the only thing keeping it alive.

A decade later, as an older and more mature Kushner prepares for the end of a presidential campaign that ought to define him as long as he lives, I find myself wishing he had kept his money, or at least properly killed the Observer off instead of tainting its name with his own.

There have been a number of Kushner profiles since he became intimately involved with Donald Trump’s campaign. They have mostly described him as unassuming and generically pleasant, with the caveat that sometimes, in private, he screams at people in anger and seeks revenge when he feels he has been wronged.

Despite those traits, I was skeptical when I read in April that Kushner was starting to play an important role in Trump’s campaign. It wasn’t because I thought it was beneath him—more that I couldn’t imagine what he could possibly bring to the table. Trump’s pitch, after all, relied on reckless pugnacity, which Kushner didn’t seem to have, and the stoking of racial and economic resentments, which I didn’t think he could identify with. It was only when the prospect of a Trump presidency started to seem real—when I pictured Trump and his family moving into the White House—that I understood Kushner’s involvement for what it was: the opportunistic gamble of a crow pursuing the shiniest object in sight.

It started, if the reporting was correct, with Kushner advising Trump on a speech to the American Israel Public Affairs Committee and continued with putting together his transition team; testifying to his tolerance of Jews; and ultimately becoming, in the words of the New York Times, a “de-facto campaign manager.” Most recently, the Times reported that Kushner was lending his “soothing, whispery voice” to the effort of keeping Trump focused and calm during the final days of the campaign.

Throughout all this, Kushner has succeeded in keeping a low profile, providing next to nothing in the way of clues to his thought process and wearing the blank expression of a Ken doll in public. The most penetrating observation about Kushner that I’ve read this election cycle appeared in a recent Tablet piece that sought, among other things, to make sense of Kushner’s feelings for the Observer as it existed under its longtime editor, Peter Kaplan. After he bought the paper, writes Chris Pomorski,

Kushner said little about the paper’s content, emphasizing its “elite readership” and “phenomenal brand,” while seeming only slightly familiar with the Observer itself. He appeared to view it coolly, as a badly-managed company with a solid name that he could leverage to turn its books from red to black. In journalism, an aloof owner is often preferable. But the reasons for Kushner’s reticence about the Observer soon became clearer: He didn’t like it. “I found the paper unbearable to read,” he told New York in 2009. “It was like homework.”

I should say two things here before continuing. First, as someone who joined the Observer near the end of Kaplan’s time as editor, I have only a tiny bit of license to identify with it. Second, I identify with it anyway, because Kaplan’s Observer and everyone who worked there are almost entirely responsible for shaping my sense of what is cool, fun, and decent in this world. It was a paper that exemplified all the traits I have come to value in people: It was friendly but not restrained or polite, confident but never boorish, athletically funny but never thirsty for laughs. The Observer didn’t just have “personality”—it had a personality.

The knock on the paper, I guess, was that its attention was almost exclusively focused on the wealthy, the powerful, and the influential, and that its small readership was made up mostly of New York’s ruling class. That was more or less true. But to dismiss the paper as “elitist” was to miss the point entirely: Yes, the Observer was interested in power and status, but the people who put it out had little of their own and didn’t particularly want more. The paper was their way of getting close enough to the action that they could see it in detail. It allowed them to sneak into the fancy party so they could notice things, hear secrets, and make jokes. Of course Kushner hated this and didn’t understand it. To him, the whole point of being in a room full of power was to go home with a piece of it.

In pledging allegiance to Trump and serving as one of his campaign’s principal enablers, Kushner has revealed himself to be the worst kind of monster: dumb but calculating, cruel but fundamentally feeble. He’s someone who should know better—in fact, he most likely does but doesn’t care, because what he stands to gain in the event of a Trump win is just too great.

There are only a few concrete ways in which the Observer has been dragged along for the ride: The three most notable examples came when its current editor, Ken Kurson, was revealed to have helped with Trump’s speech to AIPAC; when Kushner used the paper to defend his father-in-law from charges of anti-Semitism; and when the editorial page endorsed Trump in the GOP primary, arguing disingenuously that his candidacy was one of “optimism” and sneering at the “cognoscenti” who didn’t get it.

The Observer I feel nostalgic for ceased to exist long before Trump became the Republican nominee. Kaplan left the paper in 2009, and over the next few years, so did almost everyone who had worked under him. By the time Kushner installed Kurson, a family friend, as editor in 2013, the paper had—despite the efforts of many well-meaning and talented people—mostly lost the screwball sensibility that had once defined it. It was sad to me that I no longer wanted to read it, but it was also fine, especially because, at least from the outside, it appeared to still be a place where smart young journalists could learn to write and report. I remember thinking, during the editorship of Elizabeth Spiers, that not even Kushner could drain all of the magic out of a little newspaper in New York City for the simple reason that a little newspaper in New York City, no matter who’s signing the checks, will always feel like an opportunity to cool, fun, decent people.

The stench of Trump changes that. And although it may be true, as Kurson told me in an email, that the Observer is now more widely read than ever—up from 3.1 million monthly page views in January 2013 to about 19 million this past October—the place now belongs to Trump. Suddenly, articles that I might have merely ignored or dismissed as un-Observer-y—“Skulls Are Still a Theme for Watches This Fall,” “Test Driving Maserati’s New SUV, the Levante,” “17 Spooky Cocktail Recipes for Halloween”—now strike me as banal to the point of being nauseating: a kind of deadening background noise meant to drown out the boss’s evil deeds. It’s not because the Observer endorsed Trump during the primaries—it endorsed Clinton too—or because I think its coverage of Trump has been slanted: I don’t know about that and don’t really care. All I can say is that, in light of Kushner’s apparent belief that Trump should be president of the United States, I can’t help but think of the Observer as the paper we would all get delivered for free if Trump were in charge. And even if Kushner is not involved in the day-to-day work of deciding what goes in the paper—I don’t know if he is or not—I can’t help but see it as a reflection of his present situation: the newspaper equivalent of small talk and flattery, conducted to please a tacky megalomaniac.

I emailed Kurson recently and told him I was planning to write something about how Kushner’s role in the Trump campaign had poisoned my affection for the Observer. I also asked him about a moment in that Tablet piece, in which a former staffer recounted Kurson flipping through the ’90s-era work of marquee Observer writers such as Charles Bagli, Ron Rosenbaum, and Hilton Kramer and saying, aloud, “Sometimes I feel like I’m presiding over this dying paper—like I’m killing it.” Kurson initially said he didn’t understand my premise, and when I explained that I felt the campaign had exposed the paper’s owner as a stupid thug, he declined to comment.

After some coaxing, he wrote me an email citing the Observer website’s traffic growth and explained his point of view as follows:

I became a journalist so that my ideas and the ideas of writers I value can compete in the marketplace of ideas — the same inspiration I took from Rosenbaum, Bagli, Kramer and Peter Kaplan himself. We are doing that successfully. Your nasty characterization of Jared as a “stupid thug” does not describe the guy I know and it doesn’t give me the impression that Observer will get a fair hearing from you. But it does describe the state of journalism today, in which writers form an opinion that agrees with 100% of their friends’ opinions and then they write stories that confirm those opinions and those same friends tell them how “brave” the are for “speaking truth to power.” We don’t play that game. I’m proud that Observer’s editorial page endorsed Donald Trump in the Republican primary and Hillary Clinton in Democratic primary. I’m proud of the excellent journalism we’ve performed throughout this unendurably long campaign — we’ve been very tough on all candidates and also on our profession’s embarrassing double standards. So to end where I began, yes, it makes me sad that the entire business of print journalism is essentially dead. But the Observer’s future is bright and I am thrilled and excited to play a part in it.

Considering all the damage Trump’s candidacy has done, the fact that I feel glum about a newspaper I used to write for obviously doesn’t rank. It will motivate me, though, after the election, to not forget about people like Kushner, who aided Trump during his gross, spasmodic pursuit of the presidency. Some will be respectable-seeming members of society, and they will look for a way to avoid the consequences of having supported an erratic authoritarian who nakedly appealed to bigotry and fear at every turn.

If Trump goes down to defeat on Tuesday night, as I believe he will, these people will try to move on with their lives as if nothing has happened. Let what remains of the once-proud Observer serve as a reminder that they deserve our continued revulsion.