Voters are heading to the polls tomorrow, many of them taking off work or forgoing other activities to vote. So now is a good time to double-check: Is it rational to vote? And, by extension, was it worth your while to pay attention to whatever the candidates and party leaders have been saying for the last year or so? With the chance of casting a decisive vote being comparable to the chance of winning the lottery, what is the gain from being a good citizen and casting your vote?

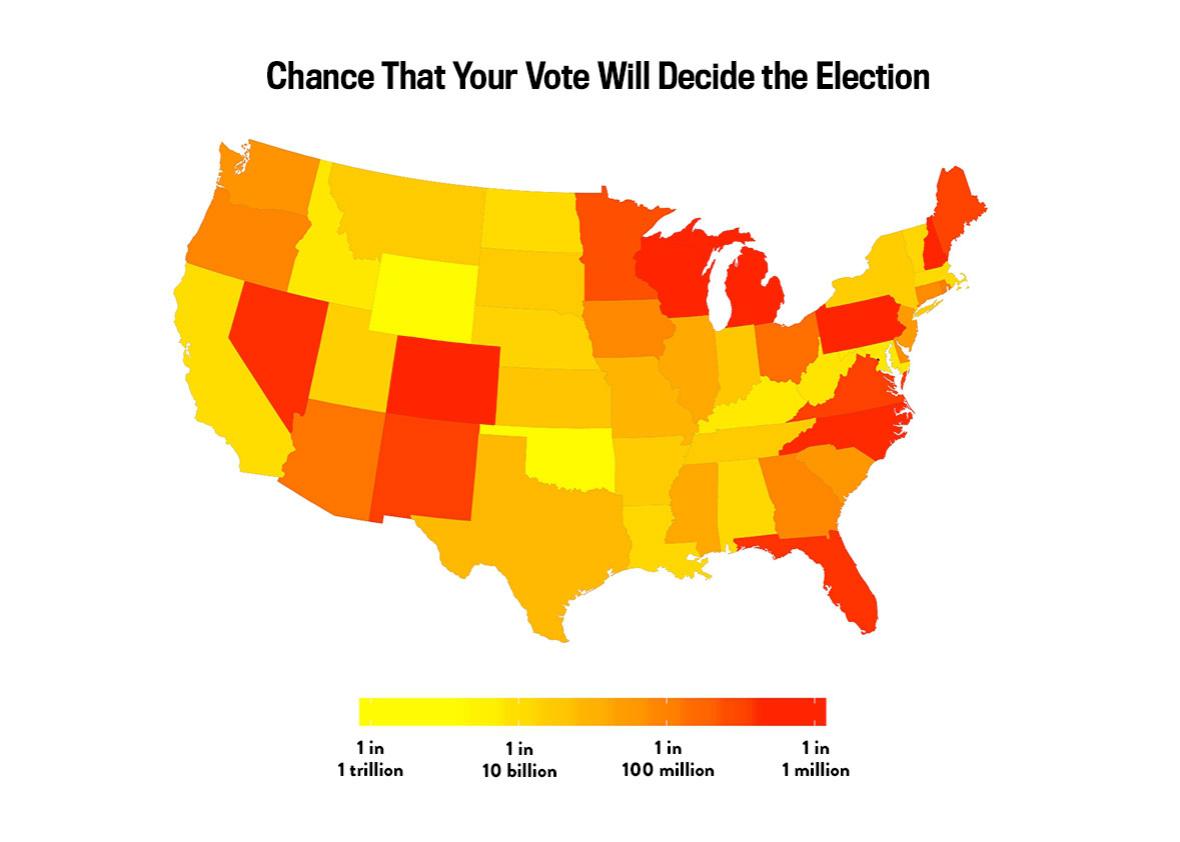

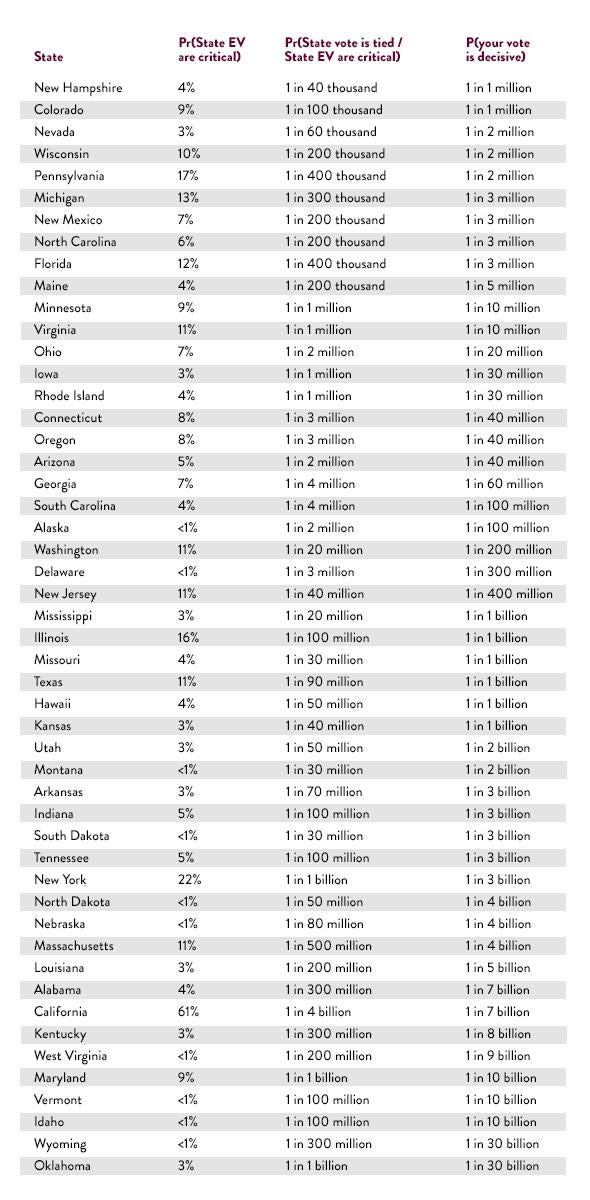

The short answer is quite a lot. First the bad news. With over 100 million voters, your chance that your vote will be decisive—even if the national election were predicted to be reasonably close—is, at best, 1 in 1 million in a battleground state and much less in a noncompetitive state. (The calculation is based on the chance that your state’s vote will be exactly tied, along with the chance that your state’s electoral votes are necessary for one candidate or the other to win the presidency. Both these conditions are necessary for your vote to be decisive, and both are highly unlikely.) So by that measure, voting doesn’t seem like such a good investment.

But here’s the good news. If your vote is decisive, it will make a difference for over 300 million people. If you think your preferred candidate could bring the equivalent of a $100 improvement in the quality of life to the average American—not an implausible number, given the size of the federal budget and the impact of decisions in foreign policy, health, the courts, and other areas—you’re now buying a $30 billion lottery ticket. With this payoff, a 1 in 10 million chance of being decisive isn’t bad odds.

And many people do see it that way. Surveys show that voters choose based on who they think will do better for the country as a whole rather than their personal betterment. Indeed, when it comes to voting, it is irrational to be selfish, but if you care how others are affected, it can be a smart calculation to cast your ballot, because the returns to voting are so high for everyone if you are decisive. Voting and vote choice (including related actions such as the decision to gather information in order to make an informed vote) are rational in large elections only to the extent that voters are not selfish.

That’s also the reason for contributing money to a candidate: Large contributions, or contributions to local elections, could conceivably be justified as providing access or the opportunity to directly influence policy. But small-dollar contributions to national elections, like voting, can be better motivated by the possibility of large social benefit than by any direct benefit to you. Such civically motivated behavior is consistent with both small and large anonymous contributions to charity.

So, yes, if you are in a state that even might be close, it is rational to vote.

Pierre-Antoine Kremp and I estimated the probability of a single vote being decisive for residents of any state (ignoring complications in those states that can split their electoral vote). Here are the places where you would have the highest chance of deciding the election with just one vote:

What if you live somewhere—such as New York or California or Kansas or Alabama—that will almost certainly not be a swing state? Then, yes, there’s essentially zero chance your vote will be decisive in the election: In the highly unlikely event that your state is tied so that your vote would swing it, the national election would be so lopsided that your state wouldn’t be needed for an Electoral College coalition. That’s why we estimate the probability your vote would swing the election to be less than 1 in 1 billion in the four states mentioned above.

Even in those states, though, I’d still recommend you cast a vote for president, if you care about the election and you think it’s important for the general good if your candidate wins. Why? Because the election could be close, and there’s a small chance that your vote could determine the winner of the popular vote. The popular-vote winner doesn’t count for anything technically, but it does give some legitimacy. Or, your vote might be enough to cause a change in the rounded popular vote, for example changing the outcome from 50–50 (to the nearest percentage point) to 51–49. Or enough to make the vote margin in 2016 exceed Barack Obama’s margin over Mitt Romney in 2012. Any of these can affect perceptions of legitimacy and mandates. This is not nearly as important as determining the Electoral College winner, but in a political environment where Donald Trump is rejected by many in his own party and where some Republican senators are declaring that they would not consider any of Hillary Clinton’s Supreme Court nominees, a perception of electoral legitimacy could make a difference. It could be worth doing your part to increase the chance that your candidate has a legitimizing share of the popular vote.

Sometimes when writing on this topic, I get the response that a single vote can never matter because if a state election is so close to being tied, there would be a recount anyway. It turns out that this does not materially affect the probability of a vote being decisive, because a single vote can also be what triggers a recount. See the appendix on the last page of this article for a full explanation—with calculus!