Sunday night’s presidential debate is a so-called town hall—a format that shrinks electoral rigmarole down to faux-intimate scale. A handful of (Gallup-selected) citizens will be in the room, posing questions to Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton. The candidates will mosey about and interact directly with these undecided voters.

The town hall concept was introduced at the presidential level in 1992. Bill Clinton requested it, and watching clips now, it’s easy to see why. He had an ease and empathy with people one on one, assuring them he was present and listening. By contrast, George H.W. Bush was so aloof (or bored, or antsy to get off the stage) that he at one point, disastrously, glanced at his watch on camera.

This year’s town hall debate will pose unique hazards and opportunities for the current candidates. Among them:

Stagecraft Foibles

In a town hall debate, there is nowhere to hide, everywhere to run. With barstools and handheld mics instead of lecterns, the candidates roam untethered around the stage. This is great if you’re a graceful cat like Barack Obama. Less great if you’re accustomed to immobile pontification.

Previous stagecraft disasters include:

Al Gore getting up in George W. Bush’s grill in 2000. The story goes that Gore had been coached to deploy his burlier physical size by sidling up to W, better allowing the cameras to capture Gore’s alpha stature. But Gore botched the tactic, clumsily getting too close in the middle of a Bush answer. Bush peered over at Gore, nodded nonchalantly, and seemed the opposite of intimidated. Gore looked like a weird guy who didn’t understand personal space.

John McCain meandering aimlessly in 2008. Juxtaposed with Obama’s svelte figure and elegant gait, McCain’s squat shuffling looked especially awkward. But things got worse when McCain began to wander the set with a purposeless mien, even managing to block Tom Brokaw’s view of his teleprompter and feeding into the perception of him as the old, out-of-touch guy in the race. The Daily Show skewered him for it.

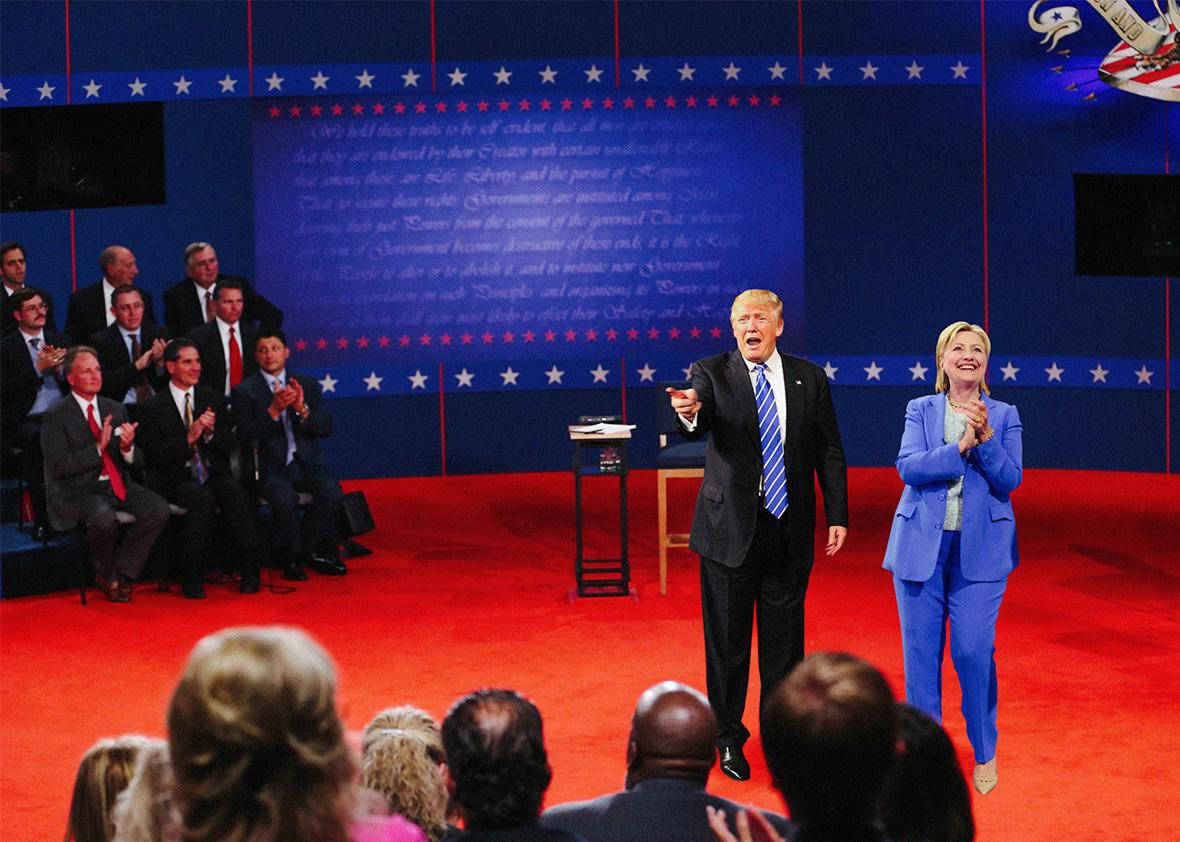

Trump and Hillary are perhaps the most physically contrasting pair of major-party candidates in electoral history. When they are forced out from behind their lecterns, and potentially standing toe to toe, the sexual dimorphism on display could be striking. Trump dwarfs Clinton, in terms of pure mass. Will this make him look more formidable, as he gazes down upon her? Or will the gender dynamic backfire on him and make him appear menacing? Consider this moment from the 2012 debate, when Obama and Mitt Romney edged closer as they argued, heating up to a near physical confrontation—and now imagine Trump and Hillary facing off in the same posture.

Questions From Regular Schmoes

Some portion of the questions at town hall debates come from ordinary voters, and not from legacy media moderators with research teams behind them. That means the candidates might face less predictable inquiries. And it means the identity of the questioner will come into play.

During the 1992 presidential town hall debate, a voter asked George H.W. Bush how the national debt had “personally affected” the candidate and how Bush could find “a cure for the economic problems of the common people if you have no experience in what’s ailing them.” It was an oddball question, as the voter presumably intended to ask about the recession rather than the national debt. It was also framed in a way that a well-paid TV network personality would be unlikely to mimic, not being one of those “common people.” It threw Bush for a loop. He was forced to look this voter in the eye and say, “Are you suggesting that if somebody has means that the national debt doesn’t affect them?”

It’s one thing for a buttoned-up moderator to ask Trump about immigration policy. It will be quite a different vibe if Trump gets a question from a Muslim immigrant standing a few feet away and has to answer to her face. He hasn’t endured much back and forth at his enormous rallies, where he stands atop an elevated stage before thousands of supporters and jealously guards the only hot mic.

Clinton, meanwhile, seems to prefer the smaller crowds and more personal interactions afforded by town halls. Earlier this week, she received a town hall question from a 15-year-old girl asking about body image. Her response, directed at the girl, would not have been as compelling had the question come from, say, Jim Lehrer.

In a new twist this year, the debate commission has promised to consider questions from the internet. Among those in contention at the time of this writing: “As president, what are the steps you will take to address climate change?”; “How will you support a free and open internet?”; and “If elected, would you support the decriminalization or legalization of marijuana?” None of those topics came up when Lester Holt was doing the asking.

Rogue Moderators

Town hall debate moderation has been fraught from the start. It’s hard to know how much of a role the moderator should play when questions are coming straight from the voters. Should she ask follow-ups? Should she hone the questioner’s inquiry?

The moderator for that 1992 town hall was Carole Simpson—the first woman and first minority ever to moderate a presidential debate. She felt it was no coincidence she’d been assigned the town hall format, writing in the Atlantic years later:

Twenty years ago when the Commission tapped me to moderate the first town hall debate, I was told the members wanted it to be an “Oprah-style” show. (Is that why they chose a black woman?). … I was simply the figure you see at so many forums—a character I’ve come to think of as “the lady with the microphone”—albeit one who was an anchor for a major television network.

No other woman moderated a presidential debate until 2012, when Candy Crowley was assigned to, yup, that year’s town hall. In statements during the runup to the debate, she promised she’d be no wallflower, which concerned the campaigns: “Both campaigns are reportedly alarmed by her statements and have pushed back—but are also operating under the assumption that Crowley may play a greater role in the debate than they’d like,” reported the Christian Science Monitor. Crowley famously did interject, with a mid-debate fact check of a Mitt Romney claim about the Obama administration’s response to Benghazi. She drew fusillades of flak for doing so.

This year’s town hall debate will be co-moderated by Martha Raddatz and Anderson Cooper. They appear to have divergent ideas about their role, with Raddatz suggesting she’d like to dig into some of Trump’s views while Cooper is hoping to be hands off. They are sure to endure cruel scrutiny, whichever path they take.

Which candidate is more likely to benefit from the format? You’d have to bet on Clinton. She seems at her best addressing people individually, not speaking to an undifferentiated mass. Meanwhile, Trump practiced for Sunday by holding a quasi–town hall–ish event on Thursday evening in New Hampshire. He used a partisan moderator, didn’t let voters ask direct questions, and cut things off early. No report on whether he glanced at his watch.