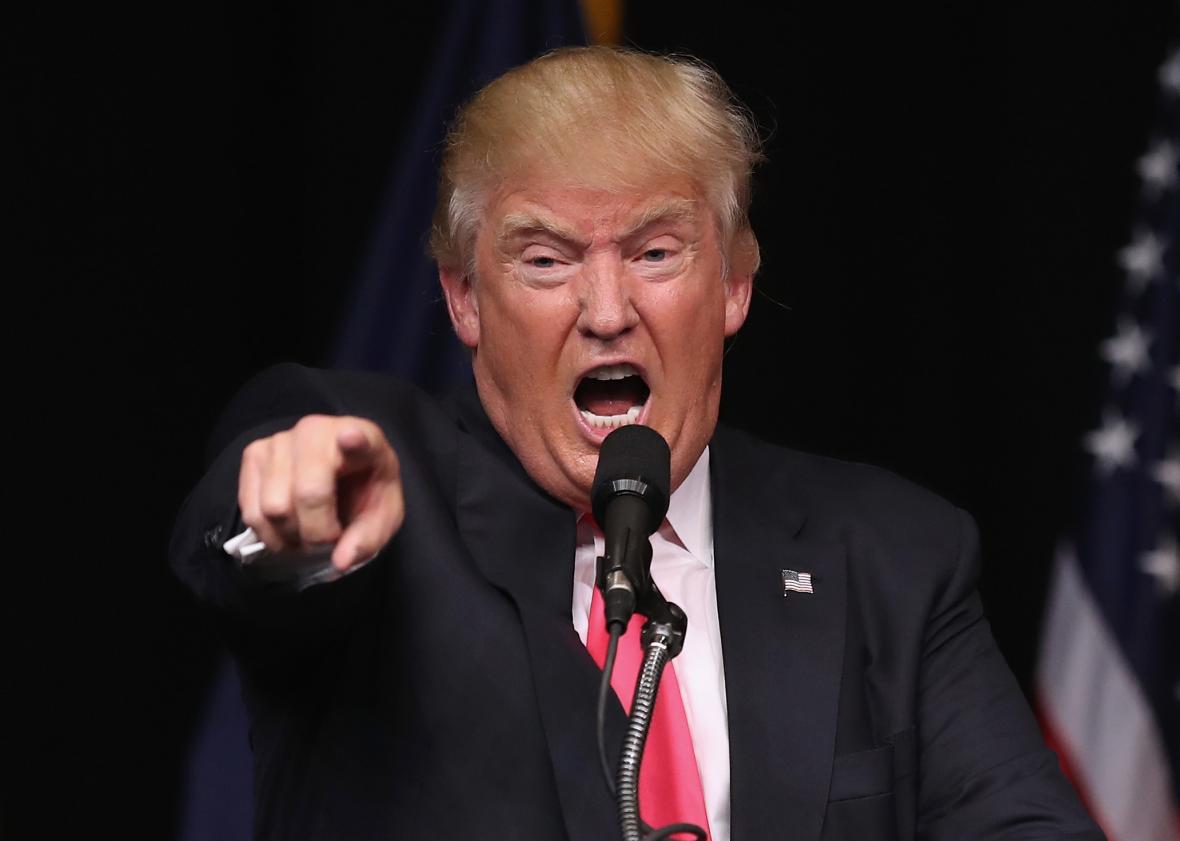

Over the past couple of days, I’ve heard many of my fellow Republicans lament that the Democratic convention offered an optimistic and hopeful vision of the American future while the Trumpified GOP convention did precisely the opposite. In his prime-time address to the nation, Donald Trump painted a vivid portrait of an America in the grip of a terrifying crime wave, a nation in which violence routinely spills across a lawless border and where working- and middle-class families have been immiserated by the self-dealing machinations of a sinister globalist elite. According to Trump, the nation is on the precipice of disaster, and only a dramatic change of course, under his steady hand, can save us. Barack Obama’s speech, in contrast, was a patriotic paean to America’s promise. Throughout the convention, Hillary Clinton’s partisans broke out in lusty cheers of “USA! USA!”

Why have the Democrats embraced Ronald Reagan’s vision of the United States as a “shining city on a hill” while the Republicans abandoned it? How is it possible that the politicians and activists assembled at the Republican and Democratic conventions are describing the same universe, let alone the same country? The answer is simple: In a very real sense, they’re not. The fact that so many smart, thoughtful Republicans are so baffled by this role reversal is, to my mind, the reason Donald Trump emerged as the GOP presidential nominee in the first place.

Successful politicians don’t choose political narratives at random. They understand that voters’ beliefs about the state of the nation are inevitably shaped by their life experiences and the ideological and cultural lenses through which they interpret them. That was as true in the 1980s as it is today. Consider a blue-collar worker who moved from a devastated Rust Belt town to a bustling Sun Belt suburb in 1984, just as the local economy was starting to boom. To this young woman, the idea that it was “Morning in America” felt exactly right. She had chosen to leave her past behind, and all the union bosses and tax-and-spend liberal politicians that came with it. Reagan’s individualistic ethos resonated with her experience, and it made her feel like the author of her own life.

But what of the blue-collar worker who remained in that same Rust Belt town and who lived through the nightmare of deindustrialization? What if this other woman saw friends lose their jobs and their homes, and what if she herself had to turn to food stamps to keep her family afloat? It’s easy to imagine her scoffing at Reagan’s rhetoric and feeling drawn to darker rhetoric. Democrats in the Reagan era didn’t sound downbeat and nostalgic because they hated America, regardless of what their Republican critics might have claimed. They came across as pessimistic because they wanted to craft messages that resonated with their voters, many of whom felt their world was crumbling around them.

What Donald Trump intuitively understands, and what all too many Republicans do not, is that for much of the GOP rank-and-file, 2016 is not 1984. Instead, the 21st century has felt like a disaster. From this vantage point, celebrating the status quo just seems perverse.

Back in February, Johns Hopkins University sociologist Andrew Cherlin put forward a theory about why working-class whites are dying at higher rates than their black and Latino counterparts. Cherlin’s hypothesis: Working-class whites feel worse off than their parents while working-class blacks and Latinos feel better off. If you’re a white man in your mid-30s without a college degree, there’s a decent chance your father enjoyed steady blue-collar employment and a stable family life when he was your age, and you do not. Native-born black men, in contrast, might compare their circumstances favorably with those of their own fathers, who often faced intense racial discrimination. Similarly, Latino immigrants of modest means generally believe themselves to be better off than they would have been in their native countries. That’s no small thing. In this sense, at least, upwardly mobile working-class blacks and Latinos have more in common with upwardly mobile college-educated whites than they do with working-class whites. And in this sense, at least, the fact that the Democratic Party is now an alliance of college-educated whites and working-class minority voters makes a certain kind of sense.

Like it or not, Reaganite optimism is not a particularly good fit for today’s GOP. The sooner Trump’s Republican rivals come to understand that, the better.