CLEVELAND—“The petitions have been signed and turned in,” Kendal Unruh said from her seat in the Colorado delegation of the Republican National Convention, as she made last-minute preparations. She was about to have her moment of truth Monday afternoon. “And,” she went on, “you’re going to watch them ignore us.”

In the past week, Unruh, a teacher, has become a folk hero to anti-Trump Republicans who insist on exhausting every last parliamentary tool at their disposal to block Donald Trump’s nomination. She and her cohort of fellow dead-enders find themselves directly in the crosshairs of RNC chairman Reince Priebus and Trump’s presidential campaign, whose No. 1 objective is to ensure a smooth, camera-friendly show of unity this week. It took a lot of effort from the likes of Priebus and Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort just to get all of these people in the building in a semi-coordinated, nonviolent fashion. Now they have to deal with Unruh and her collaborators—and they’re not shy about doing so. For a day, at least, the smoke-filled room—a relic of a time before nominees were chosen by voters—returned to the American political scene.

After Unruh’s contingent of anti-Trumpers in the rules committee failed to insert a “conscience” clause into this year’s rules package last week, an amendment that would have the effect of unbinding the delegates, they adopted a new tactic for the convention itself. The idea was that, when the rules report was brought up for passage by the full convention, anti-Trumpers would insist on recording the vote by roll call—rather than by voice vote, in which the power to determine whether the yeas or nays are louder resides with the presiding chair and his gavel. A roll call vote would be an arduous process, and it’d have the effect of emphasizing the internal discontent over party’s nominee (and of knocking the convention way off schedule). The mechanism for forcing such a vote is party rule 39 of the temporary rules under operation, which allows for roll call votes if majorities of seven delegations request it by petition.

After RNC chair Reince Priebus opened the convention around 1 p.m., the rules committee repaired to a breakout room to approve the package it negotiated last week and send it to the full convention.

After their marathon session last week, the members of the committee mostly seemed to want to get it over. When committee chair Enid Mickelsen brought up the report for approval, one stray delegate, Fred Brown of Alaska, asked for the committee to consider offering something, for the sake of “unity,” to the members who felt they were steamrolled the previous week.

Mickelsen wasn’t having it. “The chairman rules that the gentleman is out of order,” she said with a determined coolness. “We said we would have full and fair debate. No one who sat through our meeting could possibly believe the people did not have an opportunity to speak their mind.”

A round of applause broke out. The committee approved the platform, and Unruh and her allies, including Utah Sen. Mike Lee, moved on to the next thing. Important people, including Republican lawyer turned cable news rules explainer Ben Ginsberg, loitered in the back of the room, texting and making calls.

The states petitioning for a roll call vote had about one hour to turn their petitions in to convention secretary Susie Hudson. The secretary was difficult to find during that hour—some would say intentionally so. Camera crews from MSNBC showed Unruh racing through the halls of the convention trying to find her. They were able eventually to get the petitions into Hudson’s hands.

“We’ll have a vote on the floor later today regarding the rules,” a cheery Lee announced from the ground floor of the Quicken Loans Arena. “We’ll see what happens.” His understanding was that majorities of delegates from 11 states had turned in petitions demanding a roll call vote. Beau Correll, the Virginia delegate who last week won a court case against a state law binding him to primary results—not against party rules binding him—believed there were 10.

“Now we won’t be ignored,” Correll said. “Now it’s not Speaker Ryan reading the teleprompter and saying, ‘The yeas have it.’ It’s about accountability.” He added, though, that we’d have to see whether the RNC “tries to run from their responsibility of organizing the convention by the rules”—i.e., “ignores” their petitions, as Unruh had said they would.

The rules package came up for adoption after easy passage of the reports from the credentials and permanent organization committees. In no way did acting chair Rep. Steve Womack—not Speaker Paul Ryan, the permanent chair who was busy hiding from this hot mess all day Monday—acknowledge the rule 39 petitions and the roll call vote his party rules would seem to require him to hold. He just called for a voice vote. The yeas screamed and never quieted down, drowning out whatever nays there might have been.

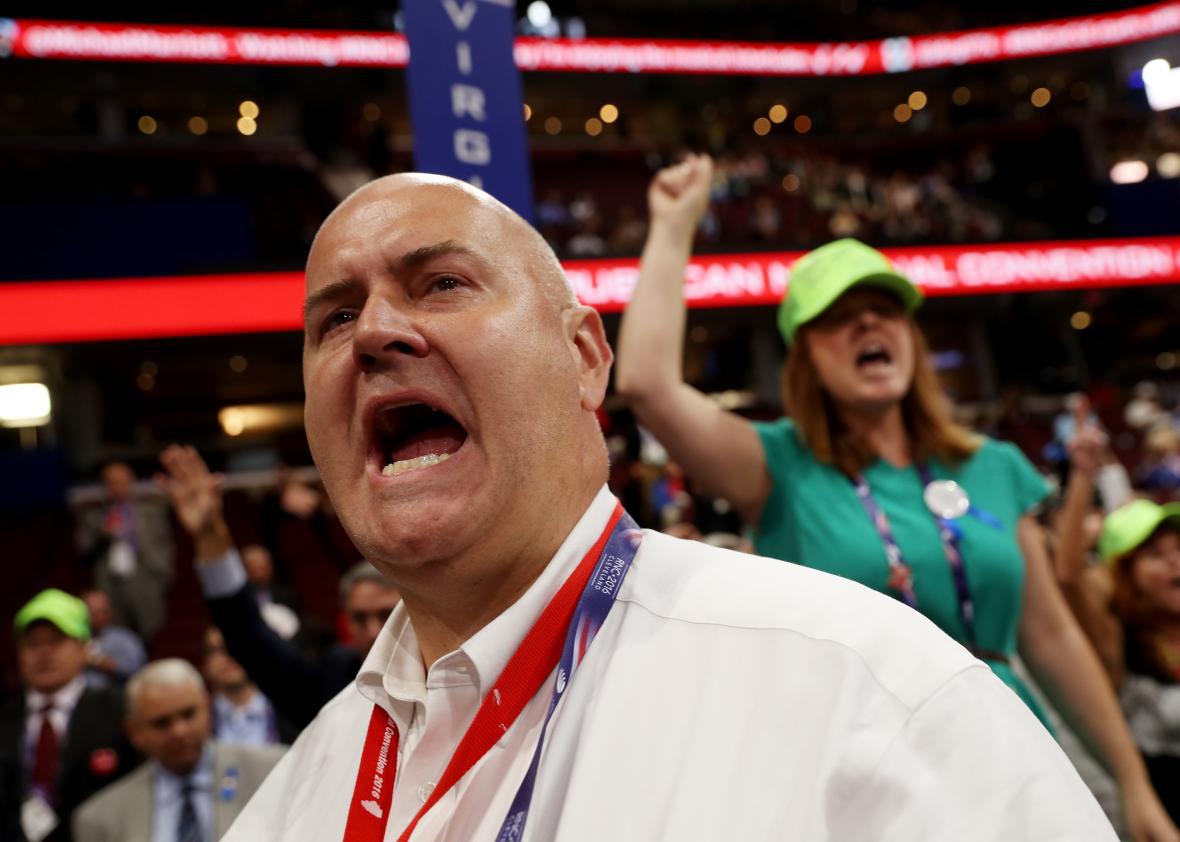

Womack gaveled it for the yeas, and the Republican National Convention went bonkers.

The petitioners and affiliated other anti-Trumpers—as well as delegates who simply thought a roll call would have been fair—began shouting “RECORD THE VOTE!” only to be met with corresponding chants of “U-S-A!” or “WE WANT TRUMP!” Unruh’s Colorado delegation discussed walking out of the convention and never returning, but first Womack, the acting chair, returned to the dais. He called for a redo to get a clearer vote. Though the yeas and nays sounded roughly equal in decibel level the second time, Womack again called it for the yeas, and then asked for objections. When the chair of the Utah delegation raised the issue of the roll call petitions that had been ignored, Womack explained that they had received nine petitions, but that three states’ petitions had been withdrawn because petitioners had taken off their names. No roll call would be ordered, and the rules package passed—again to loud, loud objections.

Which states withdrew? Unruh had no idea, and neither did Washington delegate and fellow anti-Trumper Eric Minor. Both were holding court with mobs of reporters on the floor as the rest of the convention approved the party platform. Security and police on the floor, frustrated, began screaming at the huddlers in vain to clear off. None of the anti-Trump revolt leaders—Unruh, Minor, Correll, Lee, or Colorado’s Regina Thomson—seemed to be getting an explanation from the RNC about how or why the precise number of states the RNC needed to back out were able to do so.

“If the roll call failed, we were prepared to be done at that point!” Minor exclaimed. “I would have seen it as the final nail, and we wouldn’t have gone any further. But they didn’t even allow the vote.” He hadn’t heard a word of explanation about what went down. “I don’t know if there was arm-twisting. I don’t know if there even were three states that withdrew. This is all happening behind the scenes.”

On the other side of the floor near the Colorado delegation, reporters had cornered Unruh so far back against the wall that she was leaning against the short glass barrier to the MSNBC set. Hardball’s Chris Matthews, sitting in his anchor’s chair, simply leaned back and had an ear directly to her face.

Had anyone told her what had happened? “No, of course not,” Unruh said. “And we deserve to know that, actually. We deserve to know who the states were and who the people were that they peeled off.”

I talked to a source on the floor with Trump and the RNC—“We’re married, there’s no difference, we’re all together”—who’d whipped delegates to withdraw their signatures. He showed me a Post-It note on which were scribbled the four delegations that actually withdrew: Minnesota, Iowa, the District of Columbia, and Maine. (The RNC confirmed these were the delegations.)

“We just went up to [delegates who signed the petitions] and said, ‘Hey, do you know what you signed?’ ” the source said. “And a lot of them didn’t know what they signed. Some of them thought they signed a petition that was pro-Trump, some of them thought they signed a petition that was anti-Trump, some of them thought they signed a petition that would change one rule or another rule.” What they did, he explained, was have them sign a form of their own that would take their name off the withdrawal petition. Who knows how they pitched that.

Still speaking to reporters nearby, Kendal Unruh asked a friend to grab her purse by her seat, because she worried about someone trying to dig through it.

“The RNC doesn’t want chaos in the party, but they create the chaos,” she said. “We had Trump people looking over our delegates’ shoulders taking pictures of their texts. We had Trump delegates that were standing back to deny us access.”

“This entire system,” she concluded, “is rigged to force the vote for Donald Trump.” She insisted, though, that she’s not out of plays yet.