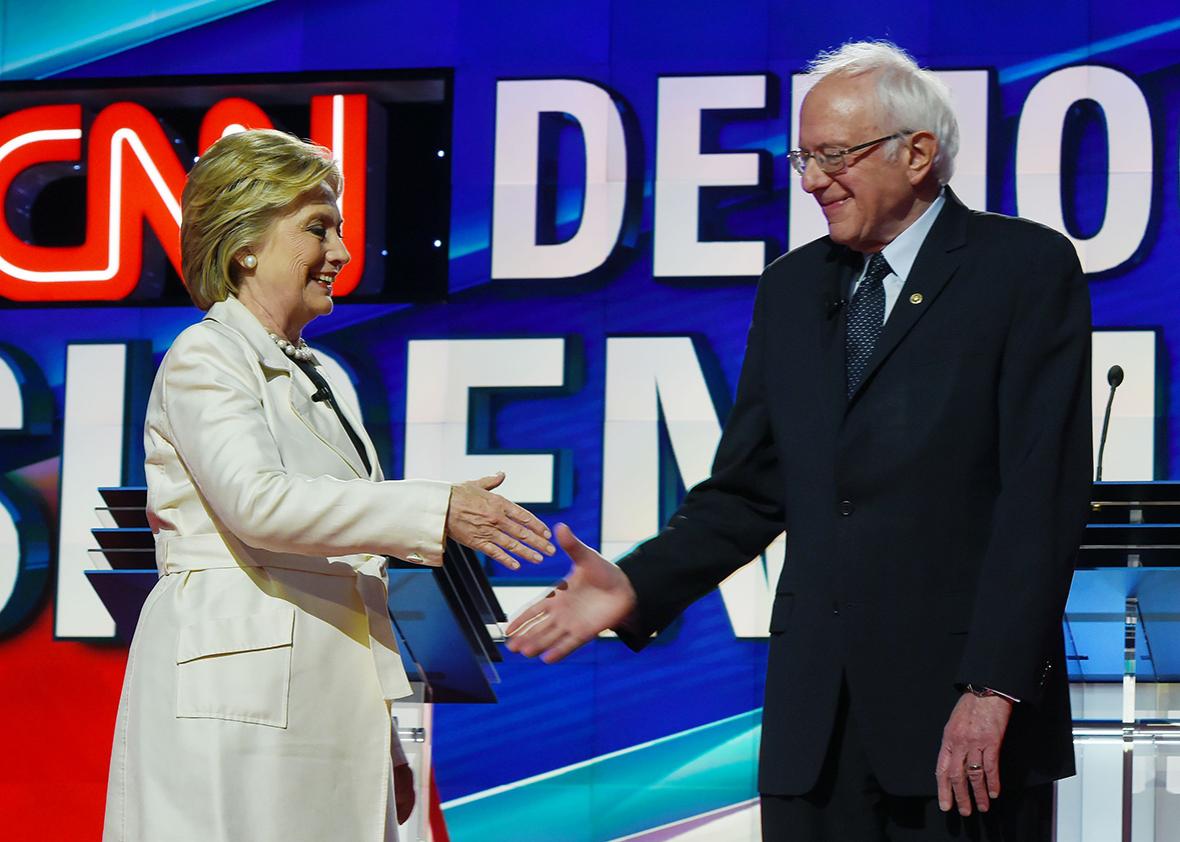

On Monday night, the Associated Press broke news. Tallying its survey of Democratic superdelegates—the cadre of party members and elected officials who help select the nominee—the AP found that Hillary Clinton had met the threshold needed for nomination. Regardless of Tuesday’s outcomes in California, New Jersey, and elsewhere, Clinton will be the Democratic Party’s nominee for president and the first woman to win a major party nomination.

Team Clinton was restrained at the announcement, telling an audience in California that “we are on the brink of a historic, historic, unprecedented moment, but we still have work to do. … We have six elections tomorrow, and we’re going to fight hard for every single vote, especially right here in California.” Team Sanders, understandably, was defiant. “It is unfortunate that the media, in a rush to judgement, are ignoring the Democratic National Committee’s clear statement that it is wrong to count the votes of super delegates before they actually vote at the convention this summer,” said campaign spokesman Michael Briggs in a statement.

The reactions fit the campaigns’ respective attitudes toward the primary. Team Clinton wants to avoid any sense that her win was unfair or illegitimate, while Team Sanders has criticized the process as suspect and, at worst, deeply unfair to his candidacy. “What is really dumb is that you have closed primaries, like in New York state, where 3 million people who were not Democrats or Republicans could not participate,” said Sanders in a recent interview with CBS News’ John Dickerson. “You have a situation where over 400 superdelegates came on board Clinton’s campaign before anybody else was in the race, eight months before the first vote was cast.”

To this point, Sanders has offered a few reforms for the Democratic primary process, aimed at smoothing the path for future ideological candidates like himself. “In those states where it’s applicable,” he said, “we need same-day registration, we need open primaries.” This is echoed elsewhere, from supporters who see closed primaries and superdelegates as obstacles to a candidacy like Sanders’, to surrogates who slam the Democratic National Committee as an unfair lever for the Democratic “establishment.” And in general, this primary season has convinced a number of observers that the Democratic Party’s process for selecting a presidential nominee is broken and ripe for reform.

I’m skeptical. To say that the process is “broken” presupposes both an idea of what it’s supposed to do in the first place and a general consensus that it didn’t accomplish the goal. We have the former: The aim of the Democratic primary process is for the party to choose a nominee who is acceptable to all of its parts, from dedicated supporters and casual voters to elites and activists, and who could plausibly lead the party to victory in the general election. But a close look at the conversation over the nomination process shows that we don’t have much of the latter—there’s no consensus over the efficacy of the process. Instead, we have an argument from the losing candidate and his backers that borders on special pleading.

To wit, Sanders’ supporters say the process is flawed because it harmed their candidate in critical ways: Closed primaries kept out pro-Sanders independents; superdelegates gave his opponent an appearance of inevitability; and the order of the calendar gave her an early advantage.

The problem is that these aren’t flaws in the process so much as they are contingent disadvantages. Yes, Bernie Sanders flailed with stalwart Democratic voters, lacked elite party support, and couldn’t win in the South. But it’s a trivial task to imagine a candidate who could have done some combination of three, or pulled a hat trick, full stop. (In fact, we have one: Barack Obama.) That Sanders was a poor fit for some aspects of the Democratic primary doesn’t mean those parts were bad. To make that call, we have to see if these parts are out of alignment with our stated goal.

They aren’t. Well before Clinton announced her bid for the White House, she held broad support across the Democratic Party. And going into the general election, she’s the clear favorite, with a modest but growing lead over her likely opponent, Donald Trump. It’s possible that—per his recent argument—Sanders is the better choice for the fall, but that doesn’t make Clinton a bad or unacceptable one.

If there’s a stronger case for reform beyond “my preferred candidate lost,” it’s that the processes of the Democratic Party aren’t especially democratic, that, together, caucuses, closed primaries, and superdelegates either preclude participation or actively subvert the “will of the people.” This isn’t wrong. Caucuses, which require long hours from participants, are notoriously inhospitable to voters with tough schedules or attachments. Closed primaries and strict registration deadlines are designed to remove independent voters from consideration. And in theory, superdelegates could overturn the decision of voters. (For weeks, in fact, Sanders was asking them to do just that.) These are real problems and dangers in the primary process as it stands. But there are virtues, too.

Closed primaries force candidates to appeal directly to loyal Democratic voters in the same way that open ones force them to win over moderates and independents. Given the degree to which this is a party selection process, that’s not only fair—it’s desirable. Likewise, caucuses are a proving ground for the organizational capabilities of the candidates, as well as an opportunity both for smaller constituencies to make their mark on the process and for underdog candidates to pick up momentum. Barack Obama couldn’t have made ground without winning the Iowa caucus, and this year’s Sanders insurgency was fueled by grass-roots activity as channeled through caucuses. They aren’t the most democratic method for selecting delegates, but they serve a vital purpose nonetheless.

The same goes for superdelegates, who represent important party stakeholders and elected officials. They force candidates—who are vying to lead the party—to take another constituency into account. Yes, the fact that they always back the pledged delegate winner undermines the extent to which they’re “unbound” (as we saw in 2008, when Clinton superdelegates switched sides to bring Obama to the threshold after he finished the contest with a lead). But this year’s Republican presidential contest is a testament to the value of an anchor in the case of a candidate who violates core party principles; an emergency brake, to use in potentially catastrophic situations like the rise of a Trump-style figure.

That the process may benefit from “undemocratic” elements gets to a larger point. Majoritarian procedures are a necessary part of democracy, but they’re not synonymous with it. And most democratic systems—including our own—are a blend of majoritarian, nonmajoritarian, and even countermajoritarian elements that translate, temper, or otherwise channel the behavior and choices of majorities. What determines if the entire system is democratic is whether it’s rule-bound, transparent, and ultimately accountable to the public.

That description fits the Democratic nomination process, and insofar as it doesn’t, only minor tweaks are needed. State parties—which control most on-the-ground election procedures—need to devise and follow common standards for registration, party-switching, and caucus participation (in states that use caucuses). If you need to register with the party to participate, it should be easy and straightforward (what happened ahead of the New York primary, for example, is unacceptable). Actual delegate selection—as opposed to allocation—should be as public as possible. And it might be time to restrict superdelegate status to elected officials, so that they can be held directly accountable by their voters.

Again, these are just small changes. Taken as a whole—and with its goals in mind—the Democratic primary process is fine. It could be better, but there’s no question it gets the job done. And Hillary Clinton, regardless of how you feel about her and her candidacy, is a case in point. To the large majority of the Democratic Party—stalwart voters, elected officials, liberals and moderates—she is acceptable, even preferable. Bernie Sanders’ problem wasn’t the process. It was that, among Democrats, he just wasn’t as popular as his rival.