One by one, the #NeverTrump dominoes are falling. Having denounced Donald Trump in the harshest possible terms on the campaign trail, Marco Rubio now tells us he will release his delegates to Trump and that he will cheer him on in his race against Hillary Clinton. Paul Ryan, the speaker of the House and conservative darling, has made his distaste for Trump plain. For weeks after it became clear that Trump would be the Republican presidential nominee, Ryan maintained that he wasn’t ready to pledge his support. But now, in an op-ed in his hometown paper, Ryan says he will indeed be voting for Trump this fall. Why now? Ryan explains that he’s had long conversations with Trump about the policy agenda he intends to introduce in the House, and he’s concluded that as president, Trump “would help us turn the ideas in this agenda into laws to help improve people’s lives.” In other words, Ryan wants us to believe that he’s not the one who has caved—that rather, it’s Trump who’s had to get on board with the Ryan agenda. We’ll see if Trump feels the same way.

It’s easy to condemn erstwhile anti-Trumpers for clamoring to find a seat on the “Trump train,” with its buttery leather seats and gold lamé interiors. But let’s acknowledge that ambitious Republicans are in a tough spot. If you’re older and on your way out of elected office, you can condemn Trump all you want and ride off into the sunset with your dignity intact. If you’re not ready to call it quits, however, there are a ton of questions for which you have no good answers.

Say you’re a young-ish Reaganite, and you dream of winning the White House some day. For years, you’ve devoted your public life to passing the ever-more-exacting ideological purity tests that have defined the conservative movement in recent years. And now you’re utterly confused. You know that Trump’s rise has upended all kinds of assumptions about what Republican primary voters actually care about. But that doesn’t tell you what you can safely assume going forward. Could it be that yesterday’s conservative orthodoxies are now completely irrelevant? Is there no longer any need to kowtow to Wall Street megadonors? Does opposing mass immigration now count for more than opposing same-sex marriage? Would it be a shrewd move to stop calling for entitlement reform and to start calling for minimum wage hikes? And what if Trump goes down to a humiliating defeat—does that mean old-fashioned movement conservatism will come back with a vengeance? No one knows, so it’s hardly surprising that a lot of right-wingers are hedging their bets.

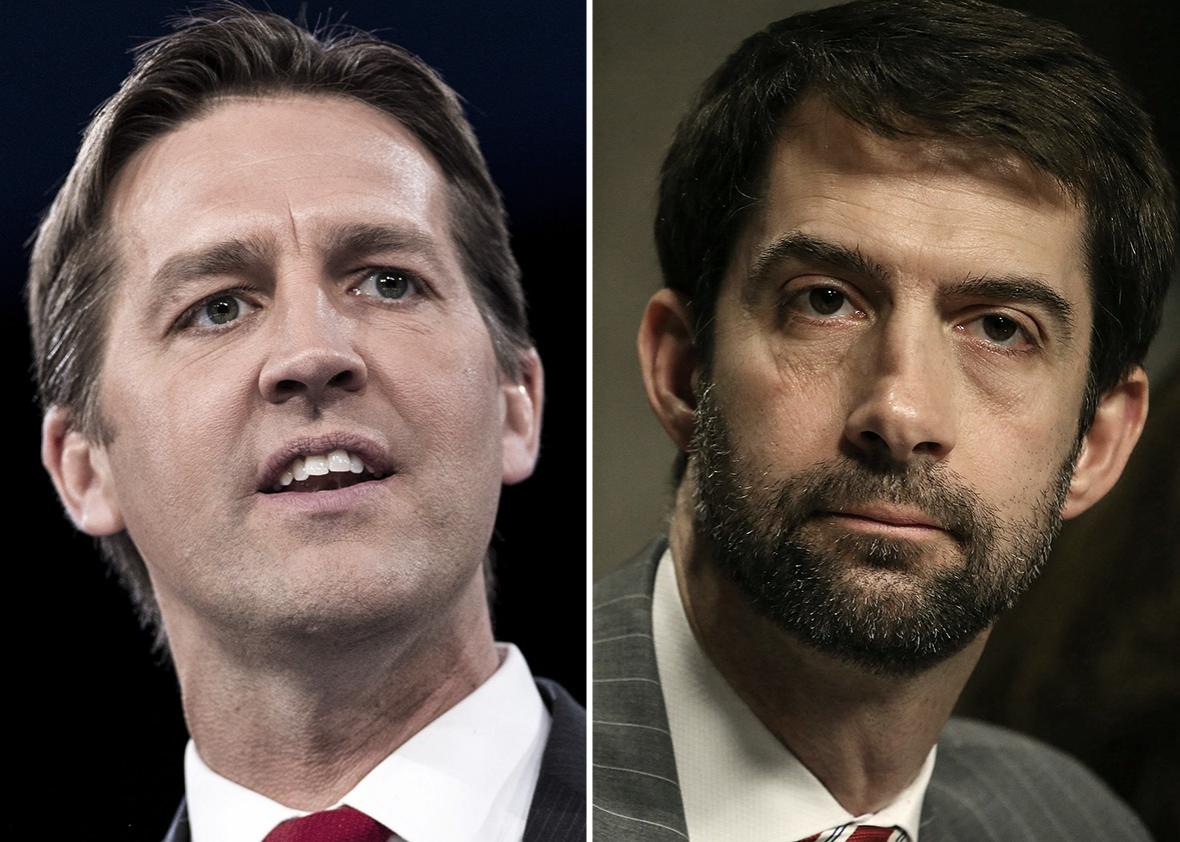

Not everyone is hedging, to be sure. Some GOP politicians are gambling on a particular vision of the conservative future. Take Ben Sasse, the junior senator from Nebraska, who has emerged as a hero to anti-Trump Republicans. What’s interesting about Sasse is that the dictates of party loyalty don’t seem to bind him all that much. In an open letter he shared via Facebook last month, Sasse offered a surprisingly tart condemnation of America’s two-party system. Though he offered a perfunctory pledge of allegiance to the party of Lincoln, Sasse also predicted that the Democratic and Republican parties were not long for this world: “It might not happen fully in 2016—and I’ll continue fighting to revive the GOP with ideas—but when people’s needs aren’t being met, they ultimately find other solutions.”

Let’s leave aside the many obstacles standing in the way of transitioning from our two-party duopoly to a multiparty system (a transition I’d support, for the record). What might that multiparty system look like? Picture a social-democratic party that takes its cues from Bernie Sanders, a Clintonian socially liberal party, a nationalist-populist party à la Trump, and a Sasse-esque party for mainstream conservatives. In our multiparty future, the Sasseservatives would be running against the Trumpistas. Sometimes they’d join together in coalition. But sometimes the Sasseservatives would join forces with the Clintonites or maybe even the Sandersites. If you believe this sort of political landscape might exist sooner rather than later—if you think the whole rotting edifice of two-party politics is about to fall apart—you might as well start blasting away now. And if Sasse is wrong and the future of the right belongs to Trump, well, there’s no shame in having fought the good fight.

But what if you believe that the two-party system is here to stay and that Trump’s voters aren’t going anywhere? In that case, you might want to craft a new, more nationalistic message that trades Reaganite optimism for a darker, more Trumpian tone. So far, Tom Cotton, the senator from Arkansas, is the clearest example of a Republican headed in this direction. Arkansas is in the heart of what Colin Woodard calls “greater Appalachia,” a region that has moved sharply to the right in the Obama era and that has proven a deep well of support for Trump. While the political influence of the white working class is rapidly declining in coastal America, it remains dominant in Arkansas and neighboring states, and Cotton has clearly taken this into account.

Though no one questions Cotton’s bona fides as a hard-right, anti-tax, small-government conservative—I recommend Molly Ball’s revealing 2014 profile in the Atlantic—he also has a populist streak. Unlike Rubio or Ryan, he rejects the pro-immigration stance of the GOP’s supply-side wing. During his brief tenure in the House, Cotton emerged as one of the fiercest critics of comprehensive immigration reform, and he’s gone on to sponsor tough immigration legislation in the Senate as well. Having recognized that minimum wage hikes are wildly popular among Arkansas voters, Cotton threaded the needle carefully, backing a modest statewide hike in 2014 while opposing new federal minimum wage legislation. Other Senate conservatives have gained “strange new respect” from liberals by opposing dragnet surveillance and embracing criminal justice reform. Cotton has done the exact opposite, championing the National Security Agency and calling for more punitive sentencing for violent offenders. If Republicans want a harder-edged standard bearer who doesn’t disguise his contempt for Beltway elites, Cotton fits the bill.

Where does Cotton stand on Trump? He’s played both sides of the fence. Last summer, he demanded that Trump apologize for his attack on John McCain’s military record, which is really the least he could do as a fellow veteran. He also opposed Trump’s call for a ban on Muslim immigrants, a somewhat harder political call given widespread support for the proposal among Republicans. In March, however, Cotton joined a delegation of congressional Republicans who met with Trump in Washington, part of the presidential candidate’s effort to woo the party establishment. Cotton was the only attendee who hadn’t endorsed Trump’s candidacy, and his presence raised eyebrows. Around the same time, well before Trump had sewn up the nomination, Cotton defended Trump’s credentials as a potential commander-in-chief and echoed some of Trump’s concerns about whether the U.S. was being taken for a ride by its NATO allies, a surprising stance for a defense hawk beloved among neocons. Now that Trump is the last Republican candidate standing, Cotton is being touted as a potential running mate. Given that he’s been a highly effective critic of Hillary Clinton’s stance on immigration—and immigration is, after all, Trump’s signature issue—he wouldn’t be a bad choice at all. If the 39-year-old senator decides to run for the Republican nomination in 2020 or 2024, as many believe he will, one can easily imagine him inheriting a decent-sized chunk of the Trump vote.

So which Republicans are going to look like bozos a year or two from now, when Trump will either be the man who obliterated the GOP or the one who permanently redefined its identity? I have no idea. But the Trump candidacy has provided a very useful sorting mechanism. In two years, eight years, or 20 years down the line, we’ll be able to look back and see where the next generation of Republican leaders stood when Trump came calling, and we’ll be able to vote accordingly.