Yes. It’s true. I was on the college debate circuit with Ted Cruz. I spent four years debating for Yale College on the American Parliamentary Debate Association merry-go-round of yellow legal pads, painfully awkward Friday-night keggers, and the infinite silliness that came with fighting for tiny silver-plated trophies each weekend. This week, watching the flameout of Cruz’s presidential run, I can confidently say that he’d have had a far more effective life in politics if he’d remained in the law.

My whole college debate experience with Ted Cruz can be distilled into a single, visceral, impression: that of being trapped in a too-small classroom in some dusty Ivy League building, with an opponent too big for the space. My memories of Ted are that he was too loud, too umbragey, and too rehearsed in an activity meant to mirror the clubby, off-the-cuff charms of the British Parliament.

Until he made it to a final or semifinal round, every moment of any debate against Cruz was experienced as a mismatch between competitor and venue. You braced yourself to be screamed at by someone who wanted it more than anyone else. And you watched as the judges—usually college students, other debaters, and some faculty—clutched the edge of their long table as Cruz opened the tap on his ambitions and flooded the room.

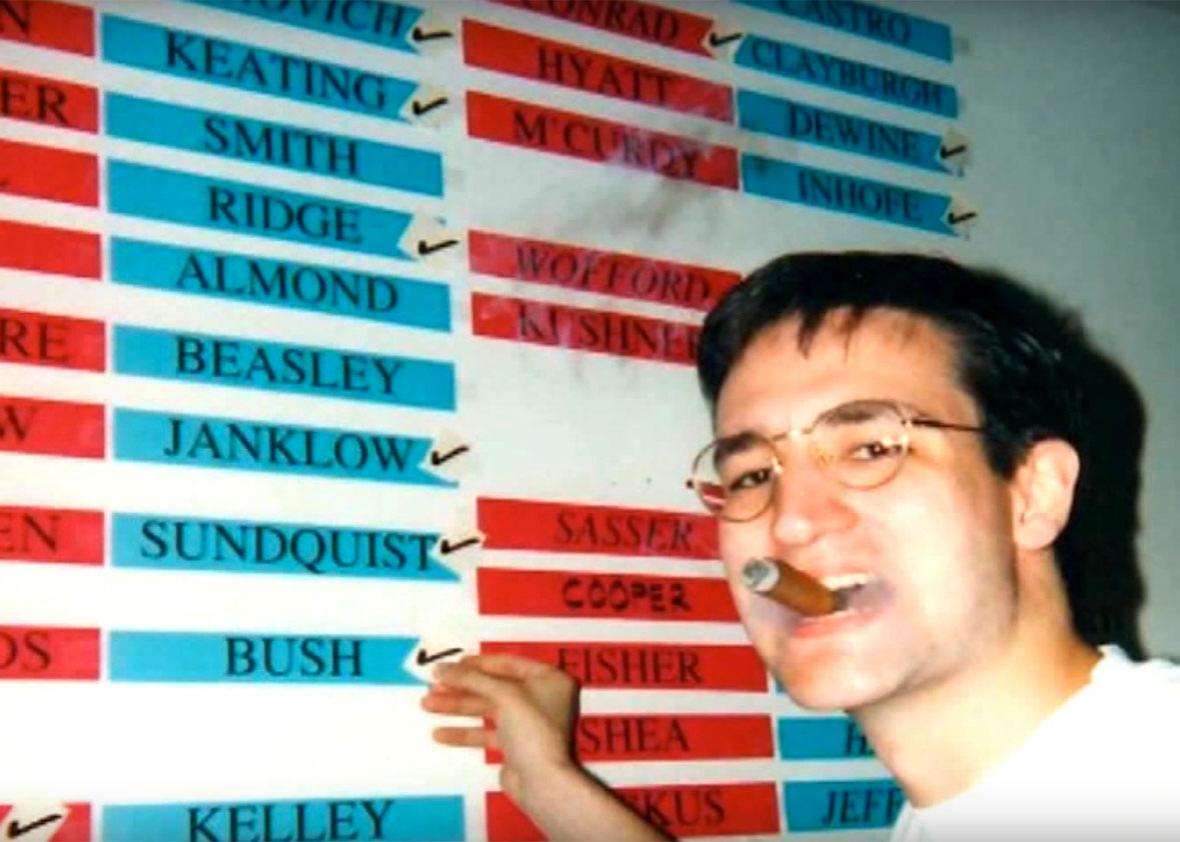

If you’ve known Cruz since college, it’s easy to say that he has changed not at all. I’ve read numerous profiles that describe his time on the parliamentary debate circuit. They describe him as a fully realized conservative firebrand at 18, someone so fiercely competitive that he would pore over his debate ballots after tournaments in order to improve future performances. He was—most of his debate contemporaries would agree—often overrehearsed for what was meant to be a fairly casual extemporaneous competition. He could be moralistic and humorless. My frequent debate partner, Austan Goolsbee, who later served as an economic adviser to President Obama, could famously reduce Cruz to a puddle of goo with a well-timed joke.

Cruz’s style invariably tended toward the pompous, achieving the unenviable end of making a fun, oratorical activity into a joyless weekend slog. He liked to reframe whatever the topic was to his own advantage, a ploy he used effectively in GOP debates throughout the campaign. (We all heard the endless recitation of his father’s arrival from Cuba to Texas with $100 sewn into his underwear, even if the topic on the table was euthanasia or the line-item veto.) And while one retrospective article described Cruz as “sort of a stud” on the debate circuit, I was struck less by his studliness than by his hyperfocused competitive instinct. Ted wanted to crush, crush, win, win, crush. He may have hoped for some Friday-night action on the side, but the real object here was the inexorable climb to the next height and the one after that.

Watching Cruz’s halting rise and crushing fall on the campaign trail this season, I’ve seen so many of the same behaviors: the canned absolutist lines; the just-add-water outrage machine; the too-loud, too-much quality that thrums through every venue until your face hurts. Putting aside the fact that someone I have been cordial with for more than 20 years has made himself hated, has come to symbolize burn-it-down government obstruction, and who still seems to make up for in volume what he lacks in empathy, I chiefly just felt regret as I watched Cruz campaign for the presidency.

That’s because I’ve also seen Ted Cruz in a room that suited his sense of grandeur (or is it grandiosity?), a room that was actually big enough to contain his staggering personal ambition, but within a system that by necessity checked most of the off-putting cravenness. To see him out on the hustings these past months, indulging in all his worst college-debate tendencies, was to see a man who had strayed from his actual calling. Like him or hate him, Ted Cruz was never a better version of himself than when he was arguing in front of the U.S. Supreme Court.

* * *

Most of my memories of debating Ted Cruz involve being hollered at. Austan was always defter than I was at deflating that which was most infuriating about Ted—the way he’d reframe a debate topic into something he had prepared, or would become fake-angry in ways that suited a 19-year-old even less than it suits a 40-something-year-old. I do remember that he wasn’t funny, and also that he never ever seemed comfortable in his skin. He always wanted to relitigate whatever round had just been decided, even if everyone else was careening drunkenly around the quad.

I have not one single memory of a relaxed Ted Cruz, or a joyful Ted Cruz, or an unguarded Ted Cruz. In every mental snapshot he is leaning forward and importuning someone to believe he is charming.

I say all this not to bury Cruz but to praise him. While I wasn’t his biggest fan on the parliamentary debate circuit, and while I have come to loathe his political ideas and his grotesque distortion of anything resembling the founding religious values, I also saw him at his unsung best. And for all the many college hit pieces, it’s worth saying that he did briefly inhabit his own skin and should be credited for it.

There was a time in the years when Cruz represented Texas as the state’s solicitor general that he briefly matched the scope of his vision to the venue, which in this case was the Supreme Court. In the oral arguments I witnessed, Cruz was constrained by the rules of the house (just for instance, Chief Justice William Rehnquist wouldn’t let him wear his cowboy boots to court) and by the constraints of law and deferential argument. At the U.S. Supreme Court there are inviolate time constraints, and subject-matter constraints, and—perhaps most of all—ego constraints. And when he argued at the court, Cruz’s operatic style suited the vast marble room and the big constitutional debates. It was the only time in his adult life that I saw Cruz and his setting matched perfectly, and because he had to rein in the worst excesses, and win votes from the justices, and follow the rules, he managed to be far more effective than he has ever been in elected office.

It’s important to understand that when Cruz took over the sleepy Texas solicitor general’s office in Austin in 2003, in part because he had burned too many bridges to succeed in the George W. Bush administration, he decided, with the blessing of then–Attorney General Greg Abbott, to transform the office into an engine for nationwide conservative causes. For the most part, I hated those causes. But under his leadership, the SG’s office went from filing an average of three friend-of-the-court briefs per year to 70 in his five-and-a-half-year stint. He filed in cases that had nothing to do with Texas, simply to have a bigger voice in the most ideological disputes around the country. Perhaps the most important case he argued in those years—presaging his willingness to go after the GOP establishment— was when he sued the George W. Bush administration in an appeal known as Medellín v. Texas. Medellín was a challenge to President Bush’s claim that an international treaty applied in the case of a Mexican national on Texas’ death row. In a 6-3 decision, the court sided with Cruz, ending the federal habeas corpus claims of the Mexican petitioner.

My experience watching Cruz argue at the high court mirrors the conclusion of Michael Kruse, who reported in Politico this winter: “In speaking to people who argued against Cruz in the Supreme Court, or who watched Cruz argue there, or who just watched him in practice arguments, called moot courts, at various law schools, I found a dominant recurring theme: He was really, really good, and he got better as time went on.”

As Kruse also noted, Cruz was perfectly at home at the court. He had clerked there for Rehnquist. He had played in the basketball games at the court’s upstairs gym. He had fully absorbed and integrated with the culture, and he knew that you couldn’t win cases there by burning shit down. It was maybe the last time he checked himself, and also the last time I found him perfectly intellectually coherent. As Kruse put it: “By the time he started appearing in front of the Supreme Court in his role as solicitor general, he wasn’t cowed by the august setting, the high ceiling with the gold trim, the smaller-than-expected courtroom, the podium that puts attorneys so close to the justices they have to look up at them.”

In April 2008, for instance, I watched Cruz argue in favor of maintaining the death penalty for nonhomicide child rapists. Subtly reframing the issue away from “evolving standards of decency” and the Eighth Amendment, Cruz reminded the court of the horrors of sexual violence against kids and that the defendant in this case, “a 300-pound man who violently raped an 8-year-old girl,” was, in Cruz’s words, “exquisitely culpable.” Classic Cruz: possibly brutal, definitely emotional, but forceful and effective.

And he meant it. He had to. At the Supreme Court, there were real consequences for institutional nihilism. When Cruz took extreme and silly positions—like when he dragged all the way to the Supreme Court a case in which, due to a state error, a Texas man was given a 16-year sentence for stealing a calculator—the high court would slap him down. That was why Cruz was able to do his very best work arguing before the high court: He could do what he does best—argue, persuade, evangelize—but he could not lie, he could not change the subject, and he could not evade the facts or the law.

Cruz had an opportunity to assume a judgeship when he finished in the Texas solicitor general’s office. He chose a different path, taking the fight to the political branches and pointing himself in the direction of the U.S. Senate, and then the White House. At that stage of his career, unmoored from reality, he became a cartoon version of the parliamentary debater I once knew. All bluster and canned outrage, untroubled by reality, and determined to smash up everything in the room. And I will just say it: I miss the old Ted Cruz. The one who argued cases I may have hated, but did so civilly and brilliantly in the only setting commensurate with his particular set of skills. It wasn’t on the presidential debate stage. And it wasn’t in the final rounds of college debate tournaments. It was in the stagey, highly scripted national theater of the U.S. Supreme Court, where politeness and humility are still the coins of the realm; where you can’t win by answering questions that weren’t asked; and where facts matter, even if you want to pretend them away.

Ted Cruz would’ve made a terrible president. He likely would’ve been an even worse judge. (Talk of him as a possible Trump SCOTUS nominee leaves me incapable of rational speech.) But that doesn’t change the fact that he was a terrific oral advocate who wasted all that talent to become a failed presidential contender.

Cruz was at his very best in those few years in which the bully pulpit was a bully lectern, and his big theatrical voice mapped perfectly onto a big theatrical stage. As a presidential candidate, he reminded me only of the humorless prepackaged Princeton debater who would say and do anything to win, for reasons nobody ever understood and none of us can remember.