The first “swing state” surveys of 2016 are here, and the news isn’t good for Hillary Clinton. According to a new Quinnipiac poll, the likely Democratic nominee is just a nose ahead of Donald Trump in Florida and Pennsylvania, where she leads 43 percent to Trump’s 42. In Ohio, she’s behind, 39 percent to Trump’s 43.

It’s a result in line with the theory of Trump’s campaign—that he can break into the Rust Belt and expand the Republican Party’s coalition to states that traditionally break for the Democratic nominee, in addition to occasional GOP strongholds like Florida.

But there’s a problem. When the pollsters at Quinnipiac took their snapshot of the presidential race, they didn’t assume a static electorate from 2012, where nonwhites were 30 percent of voters in Florida, 18 percent in Ohio, and 19 percent in Pennsylvania. Instead, in Quinnipiac’s view, a significant number of nonwhites have left the voting pool, leaving those states with whiter electorates than they had four years prior.

By Quinnipiac’s lights, today’s electorates in Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania are between 4 to 5 points whiter than they were in 2012. If national elections are determined by national swings—where most voters move in tandem, one way or another—then this implies something like a three-point swing among all groups toward the GOP, which would give Trump a narrow win in all three states, and the national popular vote. (I used RealClearPolitics’ demographic calculator for that result.)

This is possible in the same way that there’s a nonzero chance a safe will fall on your head at this very moment. But that doesn’t mean it’s likely. And when you look at the evidence, the idea that nonwhites will leave the electorate—especially in this Age of Trump—is ludicrous.

The standard narrative for nonwhite voting in a presidential year is this: Before Barack Obama, blacks and Latinos turned out to vote in modest and static numbers. After Obama’s 2008 campaign, they began to vote in droves, transforming the American electorate. Now, with Obama and his historic candidacy off of the ballot, they’ll return to the sidelines.

Every part of this narrative is wrong. A quick glance at black presidential voting shows a clear upward trend, beginning in 1996, not 2008. That year, black turnout hit a low of 53 percent. Four years later, it grew to 56.8 percent. It grew again to 60 percent in 2004, and grew slightly more than the 3.5-point average to 64.7 percent in 2008, and reached 66.2 percent in 2012, surpassing white turnout for the first time in American history.

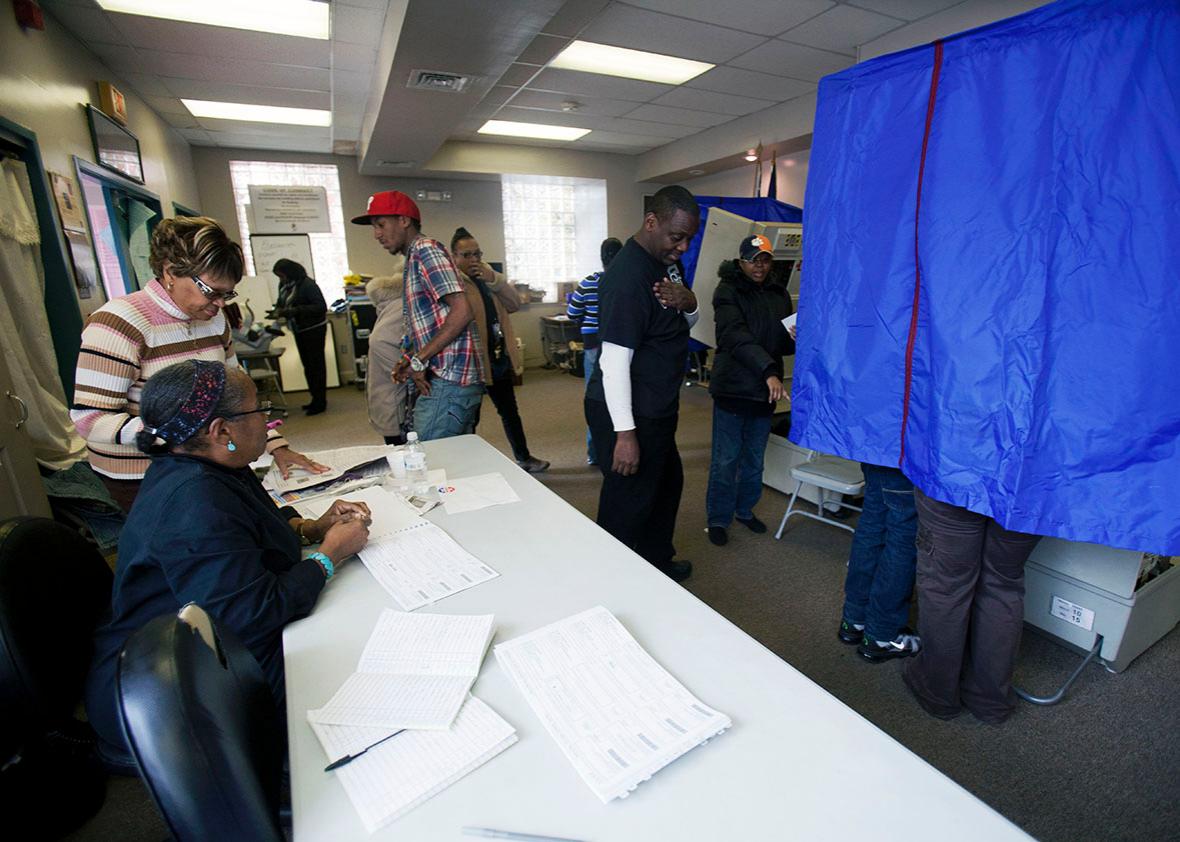

Growing black turnout preceded Barack Obama’s campaign by more than a decade. It increased on his watch, but it wasn’t a dramatic change. And more importantly, that increase wasn’t because of Obama as a figure or a symbol. It was hard work. “[D]oor-to-door, mail, phone, and Internet activities of the political parties may have been more of a factor in mobilizing Blacks than an amorphous, media-driven buzz surrounding Obama’s charismatic and historic candidacy,” write Tasha Philpot, Daron Shaw, and Ernest McGowen in a paper titled “Winning the Race: Black Voter Turnout in the 2008 Presidential Election.” This is still operative. Hillary Clinton’s primary campaign devoted substantial resources to reaching and mobilizing black communities, to great effect—in the Super Tuesday states, black voters reached or exceeded their vote share relative to the last Democratic primary, in 2008.

Hispanic turnout has also grown, from 44 percent in 1996 to a high of nearly 50 percent in 2008. But it decreased to 48 percent in the 2012 election. In general, turnout among Hispanic and Latino voters tends to lag far behind their share of eligible voters and registered voters. But there are early signs that turnout may rebound and return to its earlier trajectory. Since January, the rate of Hispanic voter registration has doubled in California and increased by large margins in North Carolina and Georgia. While some of this reflects the extent to which the country’s Hispanic population skews young, there’s evidence that it’s a reaction to Trump and his vocal, anti-immigrant rhetoric. If that’s true, we could see a growth in the total number of Hispanic voters and the share of them that go to the polls. And either way, if the turnout rate for Hispanic voters simply holds steady, they’ll have a larger impact than in 2012, given their growth in the electorate.

None of this guarantees a Clinton win or means that Trump can’t win Pennsylvania or Ohio or Florida. But it does call Quinnipiac’s assumption of a smaller nonwhite electorate—shared by many other pundits and observers—into question. The trends and the numbers suggest the opposite—that blacks and Hispanics (and Asian Americans) will again constitute a large share of the voting population, that their turnout will stay steady, perhaps even increase.

That last point is key. Trump’s nativist, anti-immigrant rhetoric is as likely to bring a nonwhite backlash as it is to bring new white voters to the polls. Trump may increase white turnout—or simply keep it steady—and at the same time dig a deeper hole with nonwhite voters as they vote against him in decisive numbers.

So far, the story of the 2016 election is the story of Donald Trump and the rise of militant white identity politics. But come November, we may have to revise that for another narrative thread: the rise of a powerful nonwhite electorate, and how it helped save the country from its worst impulses.