Three Sundays ago, just before the New York primary, I went to the enormous Bernie Sanders rally in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, to observe 28,000 Bernistas basking in afternoon sun and each other’s wokeness. Art-mope rockers Grizzly Bear played a three-song set. Actor Justin Long gave an intro speech during which he apologized for being rich. And then, at last, greeted by Beatlemania-level cheers, Bernie emerged to yell about fat-cat billionaires and imminent revolution.

Bernie had just won seven primaries in a row and gone hard after Hillary Clinton in their debate at the nearby Navy Yard. Everybody in the park seemed jazzed. Confident in their cause. Buoyed by the swell of their numbers.

You know what happened next: Hillary crushed him in New York. She crushed him again the next week in a flurry of “Acela primaries.” The delegate dorks were calling time of death on Bernie’s nomination run—practically backhoe-ing dirt over his campaign. Still, he didn’t drop out. Many assumed he’d now tone things down, stop criticizing Hillary, and play nice until he disappeared. So I flew to Indiana, the next state on the primary roster, to catalog a campaign on its last legs.

When I got there, it appeared no one had told the Hoosiers to give up the fight. At a Bernie rally in Bloomington, corn-fed college kids packed an Indiana University theater to capacity, leaping to their feet for standing O’s each time Bernie lifted his voice a notch or two above his usual bellow. A few days later, their compatriots in South Bend stuffed a convention hall to the gills, queuing up for blocks just to catch a glimpse of the sparse snowdrifts cresting Bernie’s dome.

Tuesday evening in Louisville, with Bernie doing Kentucky campaigning as he awaited Indiana results, 7,000 people stood in an outdoor, riverfront park despite the cold wind and threat of rain. These Louisvillians were every bit as pumped as their Brooklyn brothers and sisters had been a few weeks (and many delegates) before. They were psyched to boo Wall Street greed, and applaud criminal justice reform, and buy Bernie T-shirts and buttons and pins and hats and stickers.

At one point, a buzz spread through the crowd and people began to look intently at their phones. Bernie paused amid a sentence about Hillary’s Iraq War vote to make eye contact with someone offstage. “I think we don’t know,” he said hesitantly into the mic as a huge smile crept across his face. “Let’s hold off, it’s not for sure.” But it was for sure: He’d won Indiana. He was rolling on, delegate dorks be damned. Suddenly, his supporters didn’t seem quite so pitiable or naïve.

* * *

When Bernie first pinged my radar, last summer, he struck me as another in a line of irascible outsiders who tickle a certain subset of the Democratic electorate. You’ve seen cults spring up before around these high-minded, vaguely difficult men. Bill Bradley in 2000. Howard Dean in 2004. Ralph Nader in 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008 …

You can spot the type by their rumpled suits and aloof manner. See if any of this sounds familiar: Howard Dean received a flood of internet donations from an army of excited young voters. The gruff Vermonter (!) called his Democratic opponent, John Kerry, “the lesser of two evils.’” The New York Times noted Dean’s indifference to style by marveling that he “wore the same suit for weeks on end.”

Or what about this, again from the Times, but now referring to a different schlumpy, unsociable candidate: “Mr. Bradley inspired some people with the impression that he was above politics, running less as a 21st-century politician than as an Old Testament prophet, and he deliberately packaged himself as the package-less candidate, wearing scruffy suits and disdaining the hurly-burly of political attacks and counterattacks.”

The Times at one point linked Bradley and Nader by terming them both “distinctly uncuddly.” It went on to note that Nader was “cranky” and that he “regards Hampton Inns as the height of luxury because they have serve-it-yourself breakfasts in the lobby.”

When Bernie hit the scene, he immediately took up place in this club. The Times marked his arrival, impressively, by pulling off an unkempt and irascible twofer: It questioned Sanders about his tousled hairdo, which in turn prodded Bernie to bristle at the paper’s frivolity. No surprise that Bernie eschewed a tuxedo when he attended the formal White House Correspondents’ Dinner on Saturday. His refusal to ditch his humble blue button-down was solidly on brand.

What I’m saying is: There’s a fanbase out there for a candidate who can manage to exude this aura of purity, clearly. Some voters long not for a give-and-take politician but for a monk—a man descended from a worthier, less venal plane. Bernie’s campaign does nothing to discourage this notion: At the close of each rally, at the moment Bernie ends his speech, David Bowie’s “Starman” blasts from the public address system. “There’s a starman waiting in the sky. He’d like to come and meet us but he thinks he’d blow our minds.”

It’s not that Bernie’s supporters don’t care about issues. Of course they do. Every vote, for any candidate, is a hazy mélange of head and heart. We weigh candidates’ platforms against each other, but we also vote for a persona. A vibe. And to some extent, voting is a means of self-flattery—we use our ballots to reassure ourselves that we are hard-minded realists, or measured centrists, or fire-breathing radicals.

When I interviewed people at Sanders rallies and asked what had drawn them to Bernie, a few people led with corporate greed or getting money out of politics. But the vast majority—at least 80 percent—didn’t mention policy issues at all. Nobody praised Bernie because he wants to reinstate Glass-Steagall or hated on Hillary because she merely wishes to impose a risk fee on large financial institutions. It was all stuff like this:

“Bernie has imagination,” said a 75-year-old woman in Bloomington, who wore a hat with a flower in it. “We need visionaries.”

“With Bernie there’s sincerity. There’s authenticity,” said a 38-year-old man in Indianapolis wearing sunglasses and a Bernie T-shirt.

“Bernie is everything that’s good and right and fair in the world,” said a 57-year-old, skinny, heavily tattooed woman in South Bend.

Meanwhile, here’s what people said about Hillary:

“Hillary’s a typical, mainstream, corporate-owned politician.”

“I can’t trust her.”

“I don’t know what Hillary stands for. Maybe if she came out as a lesbian and let her freak flag fly …”

Of course, none of those previous cantankerous, disheveled dudes got nearly as far as Bernie has. Howard Dean didn’t win a single primary, dropping out after he finished third in Wisconsin. (Dean immediately launched a progressive PAC, which has recently been backing Bernie Sanders.) Bill Bradley quit after getting whupped by Al Gore on Super Tuesday, and he eventually exited politics to become an investment banker. (His seventh and most recent book has a hilariously marmish title: We Can All Do Better.) Ralph Nader’s quixotic third-party campaigns never amounted to much, unless you count that time he helped get George W. Bush elected. (Nader was last seen calling Donald Trump “a breath of fresh air” in an interview on the Fox Business Network.)

Meanwhile, Bernie has won 19 primaries. He’s attracted more individual donors than Barack Obama did in 2008, he raised more money than Hillary through the end of March, and he’s outspent every other 2016 presidential candidate. He’s poised to roll off a string of new primary wins in Appalachia this month. He will almost certainly prevent Hillary from getting enough pledged delegates to clinch the nomination before the superdelegates work their backroom magic. This may be a zombie campaign, but the end-of-the-road vibe I went looking for in Indiana wasn’t there. It’s not so much that his supporters are delusional about his odds. It’s more that, for once, the monk keeps winning, and they simply refuse to let the movement die.

* * *

Two weeks after Bernie suffered his dismal loss in New York, I watched about 100 Sanders volunteers gather for “get out the vote” training inside a dreary, linoleum-floored function room at Local 481—the Indianapolis chapter of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. After a briefing from a pair of national campaign staffers, they were invited to ask questions.

Seth Stevenson

One woman inquired about “voting irregularities,” and who she should call if she witnessed something suspicious. (She’d read that thousands of people—surely people clamoring to vote for Bernie—had been shut out of the New York primary.) Another woman wondered what she should say to persuade Hillary voters they were making a grave mistake. (The national staffers urged her to talk up things she loves about Bernie, not things she “hates about other candidates.”) Meanwhile, behind me, an obese man grunted at random intervals to no one in particular: “The national media won’t cover Bernie!” “Getting slandered by Hill-bots!” “I’m very disappointed in the DNC!”

At the close of the meeting, I went up to ask Aaron Robinson, the 39-year-old stay-at-home dad who’s the Indiana campaign chair for Sanders, where he thought the campaign was headed. “At this point it looks like we’re gonna go to a contested convention,” he said, “and then anything can happen. When Bernie was running for mayor of Burlington he won by 10 votes. So it’s not over.” Bernie himself held a press conference last week in which he suggested that a contested convention would be the fairest resolution.

I asked Robinson what he’d do if Hillary won the nomination and faced Donald Trump in November. “I would write in Bernie Sanders,” he said. “Hillary is part of the problem. I know that would be almost throwing away a vote.”

Roughly 90 percent of the Bernie supporters I spoke to vowed they’d never vote for Hillary. Not even against Trump. Those who said they were willing to vote for Hillary in the fall sure didn’t sound excited about it: “It always takes Hillary a very long time to do the right thing,” said a 28-year-old woman in Indianapolis.

These folks might come around, as the PUMAs did in 2008. But if they’re taking their cues from Bernie, he hasn’t called the dogs off yet. At almost every rally I attended in Indiana and Kentucky, he continued to mention Hillary’s speeches for Goldman Sachs and how much she got paid for them. Every mention of “Secretary Clinton” was met with lusty boos from the crowds, which Bernie seemed to relish. In Bloomington, a man shouted, “She lies!” and Bernie snickered in what appeared to be an appreciative manner.

Seth Stevenson

Bernie’s still grumbling a lot about the “corporate media.” So are his supporters. At the South Bend rally, an intro speaker complained that the press doesn’t pay enough attention to Bernie. The crowd spun around to glare at us, up on our riser, and booed us heartily. One guy flipped me double middle-fingers. It might as well have been a Trump rally.

But you know what? I get where they’re coming from.

* * *

I confess I can’t prove this, but I have a hunch that a lot of the mainstream, center-left media sort of wants Bernie to go away. Maybe it’s because we think he can’t win in November. Maybe we deem his policy proposals pipe dreams. Maybe we wish he’d quit dinging Hillary, because it helps the other side. Whatever the reason, while we spent a whole lot of time rubbing our hands together at the prospect of chaos in Cleveland, I haven’t seen many left-wing pundits give succor to Bernie’s call for a contested Democratic convention—even though his case is at least as legit, or maybe moreso in a strict delegate sense, as John Kasich’s or Ted Cruz’s ever was.

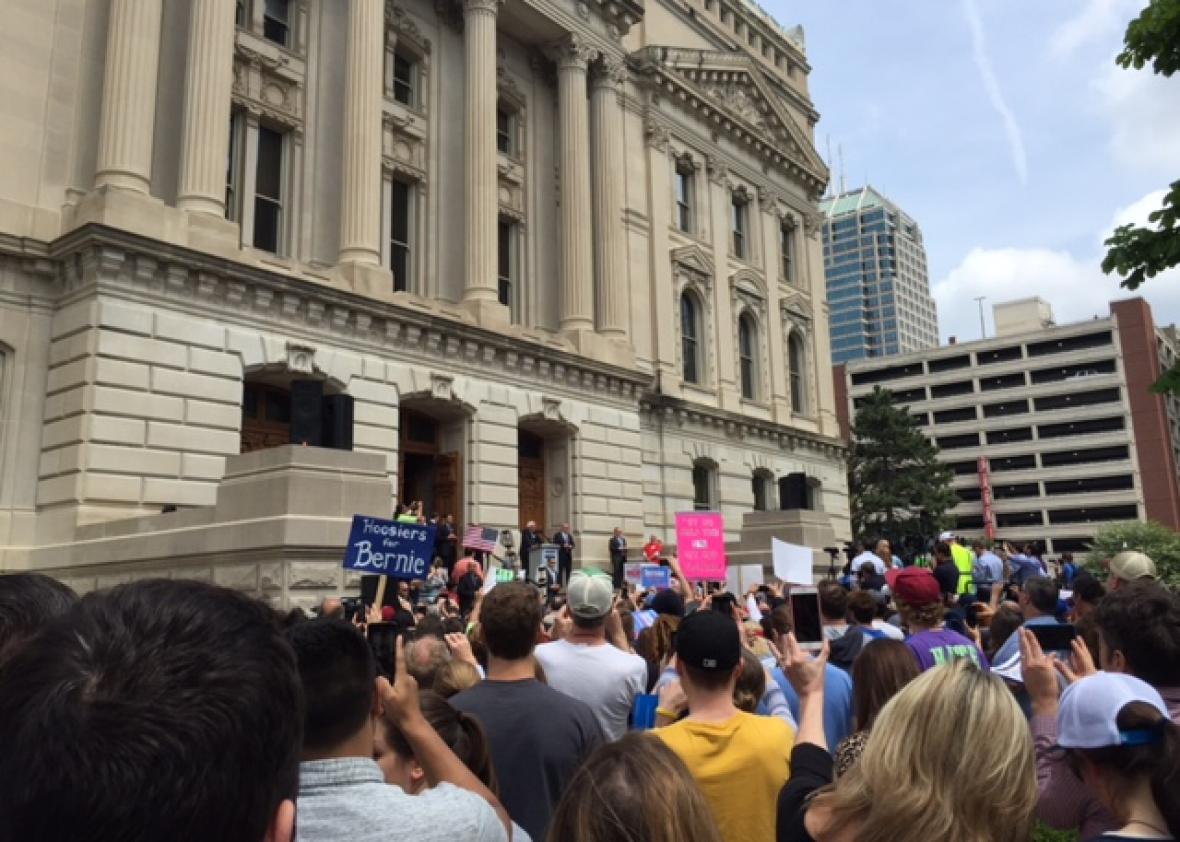

On the south lawn of the Indiana Statehouse, four days before he won the primary, Bernie took the podium at a sun-splashed Friday-afternoon rally, this time in front of a bunch of stained-sweatshirt steelworkers from USW Local 1999. The union had assembled to protest the closing of an Indiana manufacturing plant. Carrier, a heating and cooling company, is firing 2,100 employees and moving jobs to Mexico. (You may have heard Donald Trump bluster about it in his stump speech. Or perhaps you saw the viral cellphone video of a Carrier bean-counter reassuring workers that it was “strictly a business decision”—to which the soon-to-be-jobless Carrier employees retort, “Fuck you.”)

From the Statehouse steps, Bernie again hollered at the powers that be. He railed against job-exporting trade deals like NAFTA (which came courtesy of Bill Clinton) and TPP (which Hillary lobbied for, before later expressing reservations). “No more Clintons!” people shouted in the crowd. Bernie scoffed at the gall of Carrier’s parent company, which made $7 billion in profit last year and gave its outgoing CEO a $172 million retirement package, yet somehow couldn’t dredge up the cash to pay American workers a living wage.

I took a breath and reminded myself about the Kaldor-Hicks criterion, and how American consumers benefit from trade deals, and how capital will always move faster than labor so maybe these steelworkers ought to, like, suck it up and retrain to be home health care aides, and how, yes, Hillary has put forth some fairly sensible initiatives to help struggling manufacturing communities.

But a targeted tax incentive doesn’t stir the soul quite the same as an old man shrieking with righteous anger at the top of his lungs. And Bernie’s right: It is fucking outrageous. Our country is a vicious swamp of greed. It’s very hard to fault laid-off steelworkers for wanting to lynch the oligarchs and burn the whole goddamn system to the ground.

Bernie channels their outrage—truly feels it—in a way Hillary doesn’t and never will. And it’s fair for these voters to question whether she’s got their back the way Bernie does—given how palpably furious he is, and given that he’s made the fight against corporate avarice the central plank of his campaign. Hillary’s paid speeches to Goldman Sachs are not irrelevant. It’s not absurd to expect a little purity from our politicians.

I voted for Hillary in New York and I’ll vote for her again in the fall. I think she’ll make the best president of any remaining candidate, from any party. But those Bernie supporters who continue to show up for him—craving him, finding salvation in him, even as eggheads on CNN and Slate tell them he doesn’t have a prayer—I don’t think they’re immature or deluded. I don’t think they’re silly. I don’t even think they’re wrong. I went to Indiana in search of the end of Bernie’s campaign, but it’s still going. I don’t mind that.

Read more Slate coverage of the 2016 campaign.