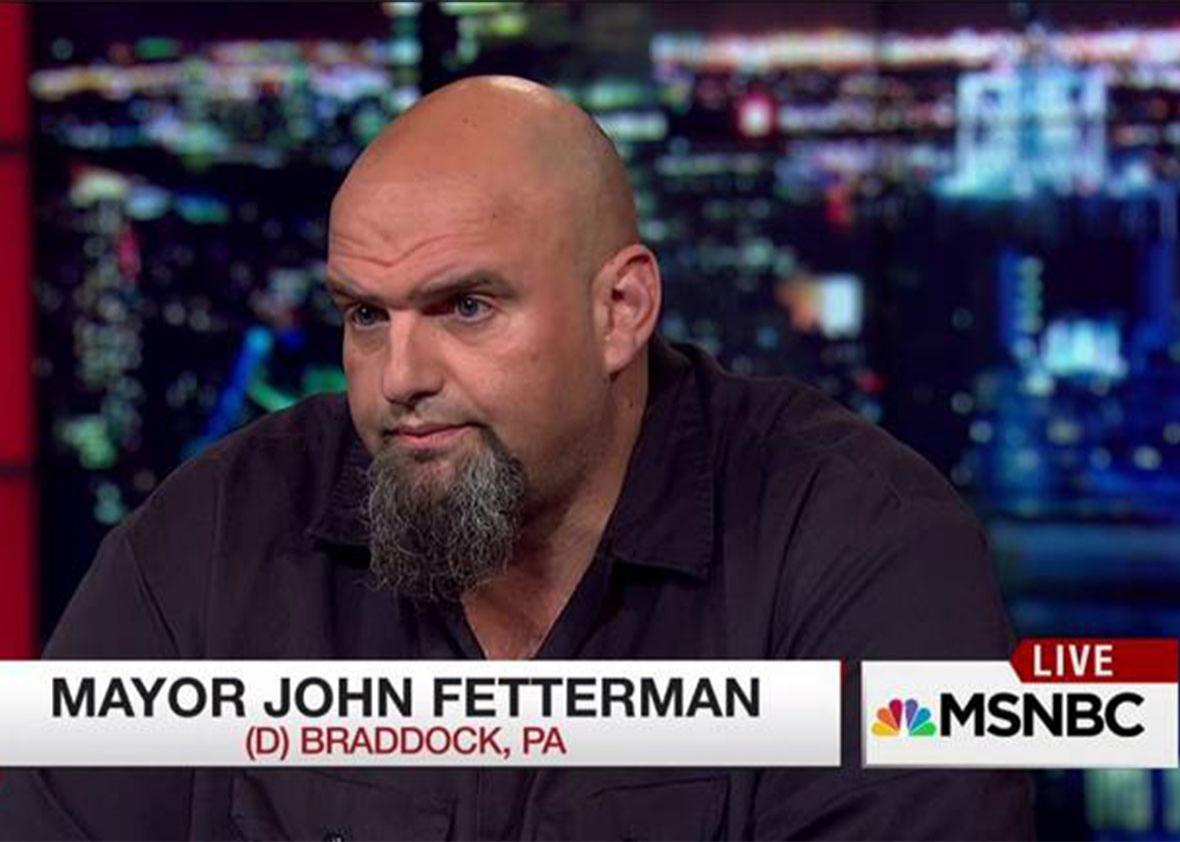

John Fetterman, the populist mayor and long-shot Democratic Senate candidate, was one of the first elected officials in the country to endorse Bernie Sanders for president. He is, like Sanders, a political outsider. A tattooed giant—6-foot-8, more than 300 pounds—he’s spent the past 11 years presiding over Braddock, Pennsylvania, a largely black town outside Pittsburgh that was wrecked by the collapse of the local steel industry. Income inequality is at the center of his campaign. “I think there’s a great deal of overlap” between Sanders’ platform and his own, he tells me, “whether it’s a $15-an-hour living wage or health care, trade deals, a rigged economy.” Ideologically, the only real difference between the two men is that Fetterman is more in favor of gun control. He has the date of every homicide in Braddock since his election—nine in all—inked on his right arm.

In February, the New Republic described Fetterman as part of “Bernie’s army,” a generation of Democratic candidates creating “a progressive revolution from within.” Like Sanders, Fetterman has raised most of the money for his primary online, from small-dollar donors. He’s in a three-way primary race against Joe Sestak, the defeated Democratic Senate candidate in 2010, and Katie McGinty, who has the backing of much of the national Democratic establishment. Fetterman’s criticism of McGinty echoes Sanders’ case against Hillary Clinton. “When she ran less than two years ago, she was for $9 an hour instead of $15,” he says, referring to the minimum wage. “She brought fracking to Pennsylvania, and she also supported NAFTA.” She has a massive financial advantage in what is currently the most expensive Senate race in the country, with more than $17 million already spent.

Given the money and political power stacked against him, Fetterman says he needs Sanders’ help to have any chance next Tuesday, the same day as the Pennsylvania presidential primary. So far, however, it has not been forthcoming. There’s been no endorsement, no fundraising support, no joint appearances. Fetterman’s campaign finds this confounding. On the ground, he says, there’s enormous overlap between his supporters and the Sanders grassroots. (“The crowd at the Fishtown brewpub is young, liberal, urban. They rave about Sanders—and Fetterman,” says a recent Philadelphia Inquirer story.) In a three-way race, he believes, Sanders’ backing could be decisive; Fetterman estimates that he’ll win if he gets 60 or 70 percent of Sanders’ voters.

Right now, that seems unlikely; a poll from early April had him at 9 percent of the vote, with 66 percent saying they haven’t recently seen, read, or heard anything about him, and 63 percent saying they didn’t know what his ideology was. The only ray of hope: When people had heard about him, what they heard made them like him more. Lacking the resources to get on the airwaves, he’s doing as much retail campaigning as he can, including going to Sanders rallies to talk to voters one on one. (The Sanders campaign didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

“To me, Pennsylvania represents the perfectly framed battle within the party war of 2016,” Fetterman tells me. “Untold millions in outside money and establishment endorsements versus the will of Sanders’ grassroots supporters who could, quite literally, pick the next nominee in this state. That nominee, badly outspent, represents a decimated steel town on society’s economic fringe.”

Sanders often says that his audacious agenda depends on a political revolution, one that would sweep progressives into office behind him. So far, however, he’s done notably little to make that happen. It’s not just his failure to support Fetterman; he hasn’t gotten involved in any Senate races. He made his first congressional endorsements just last week, sending out fundraising emails for three female House candidates: Zephyr Teachout of New York, Pramila Jayapal of Washington, and Lucy Flores of Nevada. In Wisconsin, a conservative Supreme Court candidate triumphed in part because 11.5 percent of Sanders voters didn’t vote in the judicial election, compared with 4 percent of Clinton voters.

“The president can do very little by him or herself,” says Fetterman. “You need Congress, too, and we could be somebody in the race that supports a lot of the Sanders agenda.” He’s still holding out hope that Sanders comes through: “I’m sitting here with my corsage, waiting.”

Read more Slate coverage of the Democratic primary.