At every turn in the Republican presidential primary, the anti–Donald Trump brigade has been too late in arriving.

By the time Republican candidates and super PACs began an ad barrage against the real estate mogul, it was late winter, and Trump had already swept contests in New Hampshire, Nevada, South Carolina, and most contests on Super Tuesday. He wasn’t the presumptive nominee, but he was close, and the money spent on ads wasn’t enough to stop him.

By the time Republican elites made a push to unite around Ted Cruz—as flagging candidates such as Jeb Bush and Chris Christie left the race—it was early spring, and Trump had claimed new wins in Michigan, Mississippi, Illinois, and North Carolina. And the effort to coordinate against Trump couldn’t stop him from winning Florida; knocking Marco Rubio out of the race; and claiming a large, delegate-rich state for his coalition.

At this point, desperate Republicans had formed a “Never Trump” movement meant to keep Trump from winning the nomination outright. But once again, they were too late, as any momentum gathered during Cruz’s victory in Wisconsin dissipated when Trump dominated the New York primary, taking 60 percent of the vote and all but a handful of delegates.

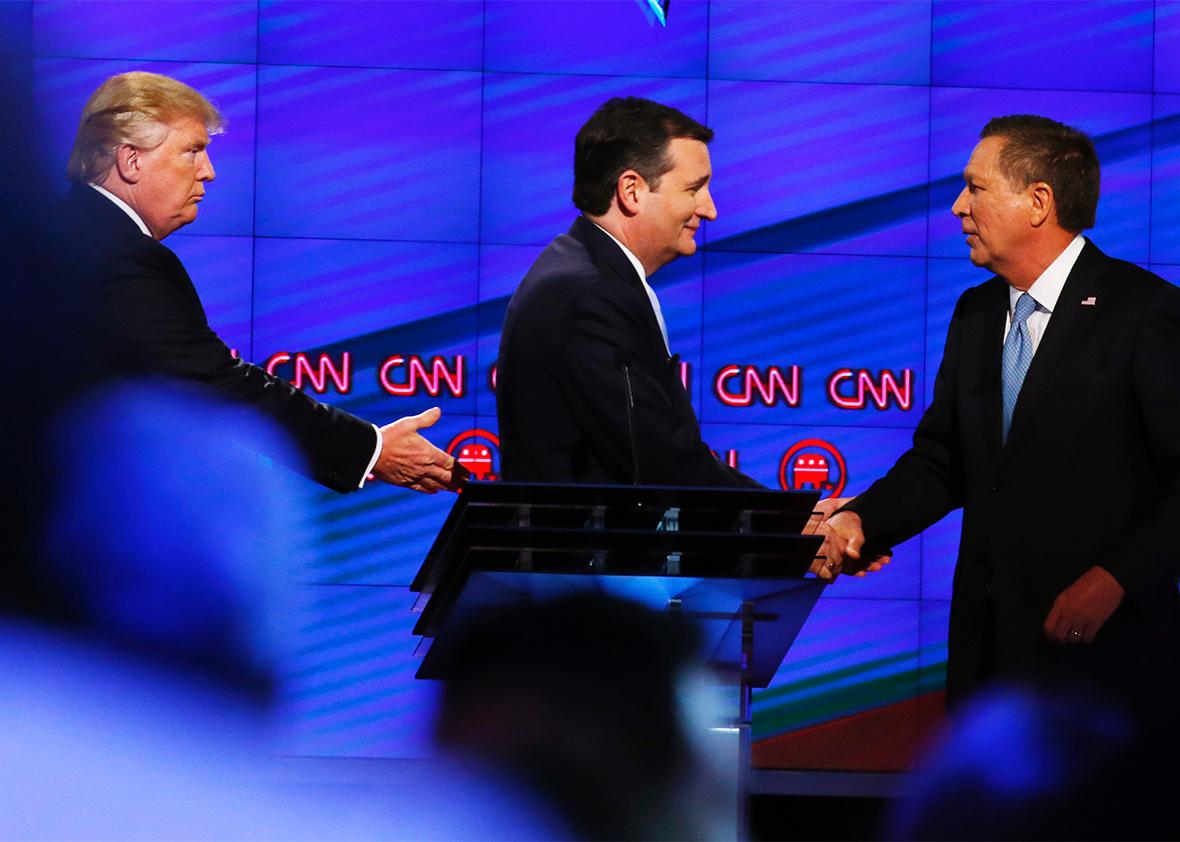

Now, the remaining non-Trump Republicans have made an agreement—call it the Cruz–Kasich nonaggression pact. Under this deal, the Texas senator will bypass the primaries in Oregon (May 17) and New Mexico (June 7), opening space for John Kasich, while the Ohio governor will give up on Indiana (May 3) to make room for Cruz, who is just behind Trump in the available polls. It’s not that Cruz backers will vote for Kasich or the reverse, but the candidates will stay out of each other’s way and campaign elsewhere. If either candidate stops Trump in one of those states, he can keep the front-runner from hitting the 1,237 delegates he needs to win the nomination, uncontested, at the convention.

Then, presumably, Cruz and Kasich would jockey between themselves for the nomination, despite the fact that most Republicans voted for Trump, who won the most states and (more importantly) the most delegates, even if he didn’t clear the bar for outright victory.

The great weakness of this scheme is that it’s delusional, full stop. And the extent to which it’s delusional is easy to understand. If we’ve learned anything watching Republicans battle for their party nomination, it’s that many Republican voters support Trump, and most (or at least a large plurality) would accept him as standard-bearer for the party. Trump is poised for victory Tuesday in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island, as well as subsequent primaries in West Virginia, New Jersey, and California. More broadly, Trump has nearly 50 percent support among Republicans nationwide and is the second choice for voters in both the Cruz and Kasich camps. According to a national survey from Quinnipiac University conducted before the Wisconsin primary, Trump would win in a two-man race against either candidate.

This is critical. Technically, presidential primaries aren’t elections as much as they are intraparty deliberations: a complicated set of rules, procedures, and contests meant to help a party decide on a nominee. Democracy, or at least majoritarianism, isn’t the point.

At the same time, it has been decades since we haven’t had a majoritarian primary. For most people, that is how this works—the candidate with the most votes wins, like in any other election. It’s why, when asked, more than 60 percent of Republican voters say that in the event that no candidate hits the threshold for delegates, the person with the most votes should be the nominee, rather than the person judged the best standard-bearer for the party. To do otherwise is to challenge a basic intuition about how the process works; it’s to ignore the public’s democratic faith. (It’s also why “superdelegates” were an object of controversy in the Democratic primary. Voters hated the idea that elites could choose a winner rather than leave the process to them.)

Cruz and Kasich might well outmaneuver Trump and keep him from his magic number with wins in Indiana, New Mexico, and Oregon, even as the bumbling start to their nonaggression pact has left them looking more like the Superior Foes of the Donald than actual competitors. But it won’t matter either way. Whether he gets to 1,237 or not, Trump has an unbeatable advantage—democratic legitimacy. And if Republican leaders try to take the nomination from his hands, he’ll have a powerful rallying cry: They’re trying to steal your vote.

For once in his campaign, he would be right. To take the nomination from the candidate with the most votes is to tell ordinary Republicans that their ballots don’t matter—that the will of elites outweighs the will of the voters. That many of those elites are elected officials—and themselves accountable to voters—doesn’t matter; that they might make a good choice doesn’t matter, either. What matters is the widespread belief that votes count and that voters have the final say on the choice of nominee. Ignoring this belief wouldn’t just confirm every possible critique of “the establishment”; it would tear the party apart.

This is why it matters that those elites were too divided and short-sighted to act quickly against Trump. By waiting until Trump had won to unleash attacks and coordinate efforts, they also lost their shot to influence voters and amass the votes needed to challenge Trump at the convention with at least a patina of democratic legitimacy. That might have worked.

Instead, they’re left with the worst possible outcome. Trump holds all the cards—he’s all but the winner. Cruz and Kasich and GOP elites can play grab-ass as much as they’d like. The simple fact is that, now, the Republican Party belongs to Trump.

Read more Slate coverage of the Republican primary.